cross-posted from YES! Magazine

Food security, traditional agriculture, and local self-reliance are key to regenerative societies of the future, say water protectors taking the movement’s lessons forward.

Sources reviewed this article for accuracy.

For Sicangu Lakota water protector Cheryl Angel, Standing Rock helped her define what she stands against: an economy rooted in extraction of resources and exploitation of people and planet. It wasn’t until she’d had some distance that the vision of what she stands for came into focus.

For Sicangu Lakota water protector Cheryl Angel, Standing Rock helped her define what she stands against: an economy rooted in extraction of resources and exploitation of people and planet. It wasn’t until she’d had some distance that the vision of what she stands for came into focus.

“Now I understand that sustainable sovereign economies are needed to replace the system we support with our purchasing power,” she said. “Our ancient teachings have all of those economies passed down in traditional families.”

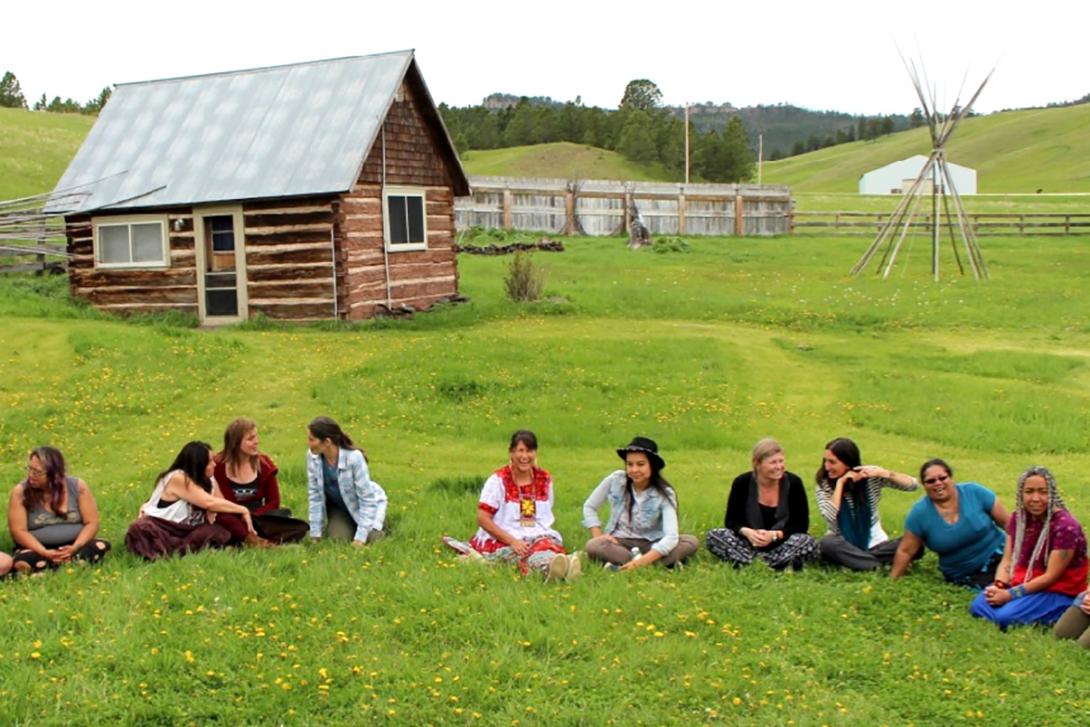

Together with other front-line leaders from Standing Rock, including Lakota historian LaDonna Brave Bull Allard and Diné artist and activist Lyla June (formerly Lyla June Johnston), Angel began acting on this vision in June at Borderland Ranch in Pe’Sla, the grasslands at the heart of the Black Hills in South Dakota. Nearly 100 Indigenous water protectors and non-Indigenous allies met there for one week to take steps to establish a sovereign economy.

The first annual Sovereign Sisters Gathering brought together women and their allies to talk about how to oppose the current industrialized economy and establish a new model, one in which Indigenous women reclaim and reassert their sovereignty over themselves, their food systems, and their economies.

“When did we as a people lose our self-empowerment? When did we wait for a government to tell us whether or not we could have health care? When did we wait for them to feed us?” Allard asked. “When did we wait for laws and policies to be created so that we could have a community? When did that happen?

“We’ve given our power over to an entity that doesn’t deserve our power,” she added, referencing the modern corporate industrial system. “We must take back that empowerment of self. We must take back our own health care. We must take back our own food. We must take back our families. We must take back our environment. Because you see what’s happening. We gave the power to an entity, and the entity is destroying our world around us.”

“We’ve given our power over to an entity that doesn’t deserve our power,” she added, referencing the modern corporate industrial system. “We must take back that empowerment of self. We must take back our own health care. We must take back our own food. We must take back our families. We must take back our environment. Because you see what’s happening. We gave the power to an entity, and the entity is destroying our world around us.”

Allard, June, and Angel shared a bit about the work they’ve been doing to establish sovereignty, each in her own way, since the Standing Rock encampments.

LaDonna Brave Bull Allard: Planting seeds

As the woman who established the first water protector encampment at Standing Rock—called Sacred Stone Camp—and issued a call for support that launched a movement, Allard learned a lot about sovereignty and empowerment during the battle against the Dakota Access pipeline.

As the camps began to dismantle in the last weeks of the uprising, she frequently fielded the question: “What do we do now?”

Allard’s response was simple: “Plant seeds.”

Planting seeds is what Allard has been doing since the Standing Rock encampment, as she’s worked with her neighbors and with those who stayed on at Sacred Stone Camp toward a vision of a sustainable community.

“I tell people that our first act of sovereignty is planting food,” Allard said. “Our first act is taking care of self. So no matter what we do, if we’re not taking care of self, we’ve already failed.”

These days, self-care is more important than ever, she said, with the accelerating climate crisis, something that Native people are acutely aware of and have seen coming for a long time. “We’re not worrying—we’re preparing,” she said.

These days, self-care is more important than ever, she said, with the accelerating climate crisis, something that Native people are acutely aware of and have seen coming for a long time. “We’re not worrying—we’re preparing,” she said.

Sacred Stone Village has installed four microgrids of solar power and have two mobile solar trailers used to connect dwelling areas that can also be taken on the road for trainings, and the neighboring town of Cannon Ball has opened a whole solar farm. They’ve been planting fruit trees and growing gardens, fattening the chickens, stockpiling firewood. And in some ways, life on the reservation is already a preparation in itself.

“On the Standing Rock reservation, as you know, we are below poverty level, and many of the people live by trade and barter. A lot of people live in homes without electricity and running water. We burn wood to heat our homes,” Allard said. “What I find in the large cities is people who don’t know how to live. And their environment—if you took away the electricity and the oil, what would they do? We already know how to live without those things.”

Lyla June: The forest as farm

A Diné/Cheyenne/European American musician, scholar, and activist, June has gravitated toward a focus on food sovereignty through her work to revitalize traditional food systems. Currently, she’s in a doctoral program in traditional food systems and language at the University of Alaska, where she works with Indigenous elders around the country to uncover the genius of the continent’s original cultivators.

“I think there’s a huge mythology that Native people here were simpletons, they were primitive, half-naked nomads running around the forest, eating hand to mouth whatever they could find,” she said. “That’s how Europe portrays us. And it’s portrayed us that way for so many centuries that even we start to believe that that’s who we were.

“The reality is, Indigenous nations on this Turtle Island were highly organized. They densely populated the land, and they managed the land extensively. And this has a lot to do with food because a large motivation to prune the land, to burn the land, to reseed the land, and to sculpt the land was about feeding our nations. Not only our nations, but other animal nations, as well.”

![Musician, public speaker, and scholar Lyla June on recovering traditional food systems: “What we’re finding… is that human beings are meant to be a keystone species… what [we’re] trying to do is bring the human being back into the role of keystone species, where our presence on the land nourishes the land.”](/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/lyla-june.jpeg?itok=CYGK8Tpz) June is intrigued by soil core samples that delve thousands of years into the past; analysis of fossilized pollen, charcoal traces, and soil composition reveals much about land use practices through the ages. For example, in Kentucky, a soil core sample that went back 10,000 years shows that about 3,000 years ago the forest was dominated by cedar and hemlock. But about 3,000 years ago the whole forest composition changed to black walnut, hickory nut, chestnut, and acorn; edible species such as goosefoot and sumpweed began to flourish.

June is intrigued by soil core samples that delve thousands of years into the past; analysis of fossilized pollen, charcoal traces, and soil composition reveals much about land use practices through the ages. For example, in Kentucky, a soil core sample that went back 10,000 years shows that about 3,000 years ago the forest was dominated by cedar and hemlock. But about 3,000 years ago the whole forest composition changed to black walnut, hickory nut, chestnut, and acorn; edible species such as goosefoot and sumpweed began to flourish.

“So these people—whoever moved in around 3,000 years ago—radically changed the way the land looked and tasted,” she said.

So did the colonizers, but in a much different way. The costs to the food system as a result of colonization, she said, is becoming clear, and the mounting pressure of the climate crisis is making a shift imperative.

“When did we start waiting for others to feed us? That’s no longer going to be a luxury question,” June said.

Besides the vulnerability of monocrops to extreme weather events, these industrial agricultural crops are also dependent on pesticides and herbicides. Additionally, pests are adapting, producing chemical resistant insects and superweeds.

“We’re running out of bullets in our food system, and it’s quite precarious right now,” she said. “The poor animals that we farm are also on the precipice … so we’re in a state where we should probably start asking ourselves that question now, before we’re forced to, and remember the joy of feeding ourselves.”

That’s June’s intention: to take what she’s learned from a year of apprenticeships with Indigenous elders in different bioregions, then return home to Diné Bikéyah—Navajo territory—to apply it, regenerating traditional Navajo food systems in an interactive action research project aimed at both teaching and learning, refining techniques with each year.

“I'm hoping at the end of three years, or four years, we will be fluent in our language and in our food system,” June said. “And we will be operating as a team—and we will have a success story that other tribes can look to and model and be inspired by.”

The long-range goal, she said, is to create an autonomous school that teaches traditional culture, language, and food systems that can be a model for other Indigenous communities.

Cheryl Angel: Creating sovereign communities

To Angel, sovereignty is best expressed in creating community—the temporary communities created at gatherings, like at the Sovereign Sisters Gathering, but also more permanent communities, like at Sacred Stone Village.

Part of being sovereign lies in strengthening and rebuilding sharing economies, she said. And part of it lies in reducing waste, rejecting rampant consumerism and the harmful aspects of the modern industrial system, like single-use plastics and toxic chemicals.

“I saw it all happen at Standing Rock; everybody came with all of their skills, and they brought [their] economies—and they were medicating people, they were healing people, they were feeding people, cooking for people, training people, making people laugh—they were doing everything. Everything we needed, it came to Standing Rock.”

“I saw it all happen at Standing Rock; everybody came with all of their skills, and they brought [their] economies—and they were medicating people, they were healing people, they were feeding people, cooking for people, training people, making people laugh—they were doing everything. Everything we needed, it came to Standing Rock.”

Despite the money the pipeline company spent to repress the uprising, she said, water protectors around the world stepped up and pitched in to create an alternate economy at Standing Rock, and millions were raised to support the resistance.

“We could do that again. We can gift our economies between each other. We’re doing it right here,” Angel told the women assembled in the Black Hills—women who were gardeners and builders, craftswomen and cooks, healers and lawyers, filmmakers and writers—and, above all, water protectors. “These few days we’ve been here prove to me and should prove to you that we have the skills to create communities without violence, without drugs, without alcohol, without patriarchy—just with the intent to live in peace.”

Published under a Creative Commons License

Go to the GEO front page

Add new comment