Most are New, Government-Initiated, and Complicated

A mix of grey- and pastel-toned buildings on San Rafael Street in central Habana stand in stark testimony to part of the effects of a cruel U.S. embargo on life in Cuba. I was standing on the street looking for a textile co-op.

A mix of grey- and pastel-toned buildings on San Rafael Street in central Habana stand in stark testimony to part of the effects of a cruel U.S. embargo on life in Cuba. I was standing on the street looking for a textile co-op.

I was part of a 28-member tour organized by the Center for Global Justice to Cuba to study worker cooperatives and socialism. I had arrived a day after the group and was trying to catch up with them. I had gotten into a taxi at Hotel Vedado with a note left at the front desk for me. The note said that the first worker cooperative our tour group would visit would be located on San Rafael between Gervasina and Belascaain Streets. The name of the co-op was missing from the note.

I handed it to the driver, excited that I would catch up with my worker cooperative tour group after missing the flight the day before. The cab driver rode up and down San Rafael a couple of times, slowed and then pointed out a general area the co-op might be. There were no signs with “cooperativa” on it and we both saw nothing that looked like a place of business, at least what I was expecting. I got out the taxi and saw a man working in a building with a gated door. I peered in.

“Donde esta el cooperativo para las ropas?“ I asked him in my sorry Spanish after offering a respectful “Buenas Dias.” “Where is the cooperative for clothing?”

He responded in rapid Spanish, instantly losing me. The dismay must’ve shown on my face. He got up and repeated what he had said, and pointed to the right.

CNA Confecciones Modelos Co-op

I eventually found the right door, an entry to CNA Confecciones Modelos Cooperativa, a clothing factory with large waiting area, a measuring room and an office.

While I waited for my group, I reflected about this trip. Cliff DuRand, a Center for Global Justice research associate who had organized the tour, wrote in one of his papers that “Cuba is poised to be the first country in history to have cooperatives as a major sector of its economy.” The Cuban state was initiating and supporting the development of worker cooperatives in the country in an effort to reinvent its economy. We were visiting at a critical moment in history.

President Obama had months before visited the country, becoming the first U.S. President to do so in 50+ years. The fear among many progressives was that the U.S. would try to economically overpower Cuba by infusing it with cash through various means to try to take back a key market. This was an opportune time as Cuba had previously opened up its economy to small private businesses in an attempt to recover from the loss of aid from the the USSR. It had, around the same time, begin to build a network of worker cooperatives as a way to strengthen the socialist base of the country.  We were here in Cuba with Cliff to learn about Cuban co-ops and how the socialist revolution was progressing.

We were here in Cuba with Cliff to learn about Cuban co-ops and how the socialist revolution was progressing.

When the Center for Global Justice tour group showed up at CNA Confecciones Modelos Cooperativa, we were taken to the large workroom where many of the co-op’s 42 workers – 37 of them women – were sewing and cutting materials. The co-op specializes in Cuban guayaberas for men and women. The guayabera are long linen shirts with pockets and are part of “uniforms” on many jobs. The large workroom had no air conditioning, but a locked gated door like the one I had previously peered through, let the Cuban breeze in and provided relief from the heat.

“Two years ago, this was a state factory with 56 workers,’ Nancy Varela Medina, presidenta of the cooperative, told our group. The Ministry had trained the four board members in cooperativism, she said, and the Instituto de Filosofia (Institute of Philosophy), which hosted our tour, was now training the remaining members. The textile co-op meets monthly to plan the work and to talk about cooperative issues, Varela said. The Ministry also decides salary and policy for the cooperative. Proud and passionate about the cooperative, Varela said that the workers now make four to five times higher salary than they did as workers for the state. Seventy percent of the net income goes to the workers. Thirty percent goes to an accumulation fund. The state is the major customer for the guayaberas.

Proud and passionate about the cooperative, Varela said that the workers now make four to five times higher salary than they did as workers for the state. Seventy percent of the net income goes to the workers. Thirty percent goes to an accumulation fund. The state is the major customer for the guayaberas.

The workers were seriously working, not paying much attention to us asking all kinds of questions about how the co-ops worked.

For detailed information, please check out our videos of the tour with English translation: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

On a Mission to Learn about Worker Cooperatives Under a Socialist Government

Our group – which consisted of mostly North Americans from the U.S., Canada and Mexico, but also a German self-management expert, a Chinese Ph.D. student, cooperative scholars Christina Clamp, Jessica Gordon Nembhard and John Curl, and several young activists – visited seven worker cooperatives: three restaurant worker cooperatives and others in textiles, construction, accounting, and transportation. Inside Habana, we also visited a Bamboo factory, a cooperative-in-the-making, and outside the city, a restaurant in Matanzas, a beautiful city with a mountainous view, called CIMEX which is part of the Monseratte Complex.

All but two of the worker cooperatives – the accounting and construction cooperative, were initiated, and materially supported by the government in some way.

I went to Cuba thinking that since the country was socialist that worker cooperatives would be the foundation of its socialist revolution. I was surprised to learn that I was mistaken on that. Worker cooperatives are a recent development in Cuba. Most of them are state-initiated and state-supported. The Cuban National Assembly edtablishes the legal framework for cooperatives. However, the decision-making within a cooperative is through a General Assembly of its members.

Although Cuba reportedly has 5,000 different cooperatives, worker cooperatives are just now getting a toe-hold in the socialist country. By far agricultural cooperatives are the oldest and largest cooperatives in the country, according to Cuban scholars we spoke with. We got to learn more during the second week of the tour when we participated in a week-long conference – the 28th Annual Conference of North American and Cuban Philosophers and Social Scientists – at the University of Habana which addressed some of the issues of cooperative development and the issues of Cuba’s socialist development. Papers from participants in our group were also presented. (See presentations in Spanish and English and video footage.)

What We Learned from Each of the Cooperatives

Taxi Rutero co-op

Taxi Rutero co-op

The CNA Confecciones Model Co-op story of re-inventing business at the initiation of the state, with continued support, was repeated with most of the worker cooperatives that we visited. Across town in the beautiful green municipality of La Lisa dotted with beautiful homes, the office and bus barn of the Taxi Rutero co-op was stationed.

Like CNA Confecciones, Rutero is a state-owned taxi cooperative. En route to the compound we passed many big mansions, some of them an impressive block-long. When our tour bus drove up to the compound painted in green which included a workshop where buses are repaired, gas pumps, and a long office building, one could see dozens of the black and yellow mini-van type vehicles that marked the cooperative.

Humberto Miranda from the Institute of Philosophy, describes the co-op as a sort of “collective Uber.”

Our tour group filed into a big conference room where the co-op holds its monthly meetings.

The co-op leadership was excited to host our group. The president, a stocky light-skinned man, was very passionate as he explained the co-op in the beginning. Miranda said that he (whose name I failed to get) had traveled to foreign countries, most recently Panama to talk about their co-op, and had met President Obama who had preceded our tour. The vice president, a short light woman, shared the second part of the discussion, an information session with all 28 of us crowded into the co-op’s conference room. Another co-op member, a black woman, served us Cuban coffee in espresso cups. They spoke in Spanish which was translated by Raul Diaz Pomares, our tour guide and interpreter who, as part of our group, was learning about Cuba's co-ops and its language on the fly.

Rutero is one of three transportation cooperatives in Havana, we were told. Each co-op has its route or coverage area. Rutero, with its snazzy black and yellow design, covers western to eastern Cuba; another with different identifying colors transports from eastern to western Cuba and one operates in central Havana. The cooperative transports between 15,500 and 16,000 passengers, whom they survey frequently to find out where they would like to travel, and routes are determined by the feedback from the passengers. In this way, passengers can collectively order a route. “The people want more and more buses,” he said. Rutero co-op was established in July of 2013. The state owns the building and the buses, and subsidizes the fuel for the vehicles at rate of 5 pesos per customer to keep the prices affordable. Their buses were imported from China, are air-conditioned, and can accommodate 25-36 passengers. All co-op policy, even disciplinary rules, is made by the General Assembly. The municipality in which the co-op operates oversees the co-op. Over the three years that the co-op has been in existence, its income was 60 million CUP ($2.27 million US). Passengers pay 5 CUC ($5 US) to ride [Cuba uses two types of currency with different US dollar exchange rates. See here for details. -ed]

Rutero co-op was established in July of 2013. The state owns the building and the buses, and subsidizes the fuel for the vehicles at rate of 5 pesos per customer to keep the prices affordable. Their buses were imported from China, are air-conditioned, and can accommodate 25-36 passengers. All co-op policy, even disciplinary rules, is made by the General Assembly. The municipality in which the co-op operates oversees the co-op. Over the three years that the co-op has been in existence, its income was 60 million CUP ($2.27 million US). Passengers pay 5 CUC ($5 US) to ride [Cuba uses two types of currency with different US dollar exchange rates. See here for details. -ed]

"In Cuba, there is an auditing body,” the president said. “We were audited every day, and we were ok."

The co-op started with 18 buses and 50 socios, or partners. The partners are the drivers, mechanics, bus cleaners, and security personnel. In three years, membership tripled.

“Now, we have 58 buses and 150 partners,” he said. Of their 150 members, 120 are drivers. "Except for driving, everybody does everything."

Drivers can work 12-hour days, with one day on and one off. Their routes are rotated monthly. The salary bonus is based on ridership and they earn based on how much the driver contributes to the co-op’s income. Every driver must bring in at least 2160 Cuban pesos a month. "The more you bring in the more you get," the president said. The co-op buys everything. The drivers earn a month's vacation a year. Ten per cent of financial contribution goes to vacation. The workers decide a scale for pension retirement. If a worker becomes 100 percent disabled, he is still considered a co-op member.

The co-op is governed by a board of five which is elected by all the workers. The co-op usually meets every three months, at 9 p.m., since that is when the co-op stops service. “The firing of anyone has to be approved by the assembly.”

"Everybody comes up with ideas,” on how to run the co-op. In the workplace, the workers belong to a union. The PCC (Cuban Communist Party) also has a cell at the workplace. PCC members are partners, but are not on the board.

"Eventually, the co-op will own the buses,” co-op officials said, and officially become a co-op. The lease fee is based on the depreciated value of the buses. The co-op says once that value reaches 0, they should own the buses.

The operation is different from how a co-op would run in the U.S. where workers do not get any support from the government. But clearly the excitement of getting to operate the co-op on the day to day basis was exciting, The presentations by both the man and the woman generated lots of questions. People were eager to ask questions and the presenters delighted in answering them.

The presentations by both the man and the woman generated lots of questions. People were eager to ask questions and the presenters delighted in answering them.

It rained just as we were readying to go. As we waited for the rain to stop, I spotted the dark-skinned black woman who served us coffee. I gave her a hug. I couldn’t help but notice that the black woman was the server and wondered whether an unconscious racial hierarchy existed – even in the co-op. Not being proficient in Spanish was a real handicap to try to get more information, but I tried. “Es una buena cooperative, te gusta?” (It’s a good co-op, do you like?) I missed the words but her non-verbal vibe was unmistakable. She loved being a part of the co-op, and she loved being involved with hosting a group of foreigners interested in her co-op. “Adios,” she said when the group started to leave, her eyes glowing. After about 15 minutes, the rain let up (which reminded me of South Florida where nature seems to cleanse the air with a little rain every day), we made our way back to the bus and over to Bienmesabe Restaurant.

After about 15 minutes, the rain let up (which reminded me of South Florida where nature seems to cleanse the air with a little rain every day), we made our way back to the bus and over to Bienmesabe Restaurant.

For more detailed information on Taxi Rutero, see videos in Spanish with English translation: Part 1 and Part 2.

Bienmesabe Restaurant

Bienmesabe used to be a state restaurant that went bankrupt. Now it is a cooperative. When we walked into the airy space with windows, food was laid out buffet style. Most of the customers seemed to be locals. A couple of workers in white aprons proudly stood behind, ready to be of service. The restaurant gave us a meal for 10 CUCs each, and it was probably the best food that I experienced in Cuba, but I am a vegan so my experience was limited. I had lots to eat: beans, a corn dish, that I could barely get enough of, plantain, vegetables and rice. The meat eaters were happy with a choice of carne.

“We turned it around by changing the menu, providing better quality food, improving the décor and advertising,” the manager, a black woman, told us after we had our meal. There were 23 members, half of whom were former state employees. The Ministry supplies ingredients at a 20 percent discount and they can contract for supplies from private and co-op sources, she said. Like other co-ops, the National Assembly sets the pay scale. However, pay is not equal. Some workers earn a percentage of the profit depending on the kind of work they do. There is no job rotation, but the pay is an improvement over when it was state-run. “The pay is way better,” she said in her presentation.

As we were leaving and the manager said goodbyes, I asked her how was the racial situation in Cuba.She seemed shocked by the question. She said there were no divisions along color lines, and if I understood her rapid Spanish correctly, she was considered “white.” Maybe she meant in the same way that black people were treated.

Young people starting a bread factory

When we returned to Bienmesabe for coffee after our Rutero tour, we heard from six young men who are planning to start a bakery co-op.

Miranda introduced their presentation by explaining that young people made up the bulk of Cuba’s population. He said that only 20 percent of the Cuban population is over 60.

![At the Bienmesabe Restaurant, Institute of Philosophy’s Humberto Miranda introduces four young men who plan to start a bakery cooperative. Photo by Paul Nadeau.]](/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/fouryoung_cooperators.jpg?itok=CIS2MmMM) “The dream of many people is to drive a BMW and wear $180 shoes,” Miranda said of the young men, one of whom was his son. “This not their dream. They want to stay (in Cuba) and serve their country.”

“The dream of many people is to drive a BMW and wear $180 shoes,” Miranda said of the young men, one of whom was his son. “This not their dream. They want to stay (in Cuba) and serve their country.”

The young men grew up to together, playing sports and doing other things in the neighborhood. When they got older they started to think about what they could do to earn a living. "We’ve known each other all of our lives,” Miranda’s son said. “We were a co-op without thinking about it; we were a natural co-op. We share feelings, ideas and we work together doing something meaningful.”

One had thought of woodworking. One of them, Yeo, worked in a co-op before. Another went to meetings for a taxi co-op. The friends “did a little research about the options we have.” One of them said since Humberto worked with cooperatives, “We came to talk to the master,” he said in English. “We are so pumped. We will start a bakery to produce bread and other products out of flour to supply schools in the community.”

“It’s hard and we know we want to do something. We want to do it in a cooperative way because it’s the way we live. What a beautiful thing to do and help other people.”

The friends have already found a master baker who will be a part of the co-op and teach them baking skills. The young people have been hard at work. The night before the presentation, they stayed up past midnight “writing the rules of the co-op,” one said. The process is to become legally accepted as a co-op and then apply to the Ministry.

In the meantime, they are educating themselves on cooperatives and baking.

Someone asked where they see themselves in five years. “We are producing bread for Cubans,” one said.

Said another: "One day we will make cheese bread for you."

CREA Group - A Construction Cooperative

Crea means “to believe,” in Spanish, and it is the name of a construction worker cooperative in Havana. Crea is a great cooperative and works to help workers make a living as well as to afford housing, and to recycle the island’s goods. Crea was formed eight years ago from both privately-owned construction groups and state-owned companies.

Crea was formed eight years ago from both privately-owned construction groups and state-owned companies.

For the first five years, their numbers remained at about 20. Now they have 45 people, six of whom manage the cooperative. “We all are engineers, equally divided between men and women,” said Ariel Fernandez Calzadilla, an engineer and the co-op’s president, who came to the Institute to talk to the group about their cooperative. “The rest are ordinary workers, plumbers, electricians, carpenters. The co-op has hired workers or contractors when they are needed to supplement the work.” Because of the complexity of the work their goal is not to construct buildings nor do they work on high buildings.

The group formed the co-op because they were "interested in doing things so that the social impact can be shared with other people,” Fernandez said. "Despite the fact that we live in a socialist country, the revolution has taught and trained us to be in solidarity with people. It has been easier for Cubans when it comes to sharing the work [in order] to find solutions to everyday problems.” When Crea contracts a job, the company recycles wood, appliances and other materials from the worksite. The co-op pays an outside person to fix hard-to-find and expensive appliances which can be used to help refurbish cooperative members’ homes. “That has been hard for us to do,” Fernandez said.

When Crea contracts a job, the company recycles wood, appliances and other materials from the worksite. The co-op pays an outside person to fix hard-to-find and expensive appliances which can be used to help refurbish cooperative members’ homes. “That has been hard for us to do,” Fernandez said.

Conditions in Cuba mean that at one point or another many of the worker cooperators will need help. “Everybody needs a house or some rehabilitation,” Fernandez said. Because Cuba is an island, the salt from the sea corrodes buildings quickly, Fernandez said.

In addition, because of the U.S. embargo against the county, many items the co-op and ordinary people need are in short supply: appliances, construction materials and machines. In addition, Cuba has no wholesale stores, and items in retail can be expensive or difficult to obtain even from other countries because the United States financially penalizes any country who does business with Cuba.

To help each other cope with the hard times, the co-op has evolved a unique way to lend a hand by helping the workers with things that often money cannot buy. Sometimes that is building a house. Sometimes it is help refurbishing a house. Sometimes it is something smaller.

“We know how these people live. We realize the people who need this help. They have children. They do not have all of the necessary conditions,” he said. The administrators choose a member who needs help, and work up a proposal to present the co-op.

“We take this proposal to the group. We analyze a budget [and ask ourselves] ‘Do we have the finances for this?’ People agree. Then we do the work. Sometimes people are surprised because they are not expecting this to happen. We use this to encourage people, so they can become familiar with the way of thinking in the group. We have done several things [in employees’ homes]: the floor, ceiling, paint, carpentry.” This creates a sense of teamwork and loyalty. “Things have to be shared,” Fernandez said. “When people are constructing our houses we support them with material resources at cost so that they can have credits and we support them in construction of their houses. We pay others who work in other people's houses. Money is shared for gas and construction.”

“Things have to be shared,” Fernandez said. “When people are constructing our houses we support them with material resources at cost so that they can have credits and we support them in construction of their houses. We pay others who work in other people's houses. Money is shared for gas and construction.”

This sharing is critical to building team work, which Fernandez says is critical in construction and complicates the work. “Now people learn they will [be the] solution to other people's problems. You're going to be paid for that. He learns he is going to do the work for his fellow workers.”

Fernandez said so they use these to help workers resolve issues at home, such as relationship problems and excessive drinking. "Workers always think about their personal problems,” he said, and they sometimes need help working them out.

University of Habana professors have organized psychological conferences to help the workers “learn to be better men.” This creates better workers, Fernandez said. “If you are a better human being, you will be a better professional in the end. We had a hard time transmitting these ideas to workers. “

The co-op meets every week to plan their work and every month to a month-and-a-half for popular information and education. All workers are invited and clients as well. They organize other activities, such as collective birthday parties and baseball games. And they celebrate their successes at work. “Every time we finish one job, we celebrate it,” Fernandez said. “We go some place to eat. We give some things to the people to recognize people. This goes beyond people being paid. Sometimes we buy things they need in the house, not the person: plates, glass, things that families actually need. It is important that the family know the recognition that he has with his job. “

All of this is a process that they have worked out over the years to build teamwork.

“It is very important to work in teams to do construction work,” he said.

"In the end, we are going to have better people and better workers,” Fernandez said. “They feel they are making enough money because they come to work every day. When we ask them to do difficult things under difficult conditions they are there to do it. “

The program has been very successful, though very difficult, Fernandez said.

"It’s been spectacular, and the impact it has had on the guys has been very important. "

In this way, being a worker cooperative "is a strength.“ Working to help fellow cooperators helps them to become “identified with our own way of doing things.”

Not everyone needs this kind of support, he says, but for those who do, it is a boon, better than a paycheck.

The co-op is finding success. “We have been able to maintain 40 people working very hard for three years,” Fernandez said. "People feel that they have a guarantee that they always have work to do."

In this way, one day at a time, the group helps to build the socialist revolution.

"Before a man can think politics, they need to eat," Fernandez said.

El Biky Restaurant

Unlike most of the other worker cooperatives that we visited, the El Biky restaurant was self-initiated, self-funded and is one of the swankiest cooperatives we visited. Located at Infanta #412 e/ San Lazaro and Concordia streets, in central Habana, it consists of a restaurant and a bakery. The 1,600 sq.-meter building had been vacant for 10 years. It had a life first as a state pizza restaurant and then a short-lived vegetarian restaurant.  "This is a gastronomical complex," said Mr. Castelano, who spoke in English to the 30 or so people crowded into his second-floor office. The complex includes a bar-café, and bakery. The restaurant uses white table cloths and napkins and has waitstaff dressed in white with black ties. The food is plentiful and includes traditional Cuban food as well as pizza and burgers and other foods, presented beautifully. The menu is diverse, except for no options for vegans but a salad and chips. The manager said 90 per cent of its customers are Cuban.

"This is a gastronomical complex," said Mr. Castelano, who spoke in English to the 30 or so people crowded into his second-floor office. The complex includes a bar-café, and bakery. The restaurant uses white table cloths and napkins and has waitstaff dressed in white with black ties. The food is plentiful and includes traditional Cuban food as well as pizza and burgers and other foods, presented beautifully. The menu is diverse, except for no options for vegans but a salad and chips. The manager said 90 per cent of its customers are Cuban.

El Biky opened its doors in December, 2015, after obtaining authorization to start the cooperative in February, 2014, having formed a year earlier. The co-op secured a loan from the Metropolitan Bank at 6.5 per cent interest over 8 years, two other private individuals and membership to renovate the building plus money from a private source. During reconstruction of the building, 20 people a day would stop in and ask for a job. They were told they could join the co-op and many – about 90 percent – did. After interviewing and selected the best, the co-op has 120 associates, 95 percent of whom are co-op members; the other 5 percent are hired. The share, or member fee to join the cooperative, was 1,000 CUCs.

The co-op doesn’t own the building but they can lease it at a fixed price for 10 years. “This is the difference between state and private,” he said.

Despite individual investments, Castelano said it is a co-op in the sense of “one-member, one vote.” Income varies by the job – cook, waiter, door persons, cleaners. Every month they vote on wage levels. Waiters receive 10 percent of sales, plus tips. Like the transportation cooperative members, they work 12 hour shifts on alternate days. Cooks can not make the same amount of money, Castelano said, “because they do not contribute the same because of added value.” But the General Assembly has the final say in the value of each job.

The workers are part of the trade union, which settles any differences among workers. No Party cell is on the worksite, the manager said. He is not a PCC member and has no political or religious link, he said.

Five people comprise the co-op’s board and they “control the co-op,” he said.

During a question and answer period, Castelano responded to a question about whether a private bank could harm the cooperative, he said: "Banks always win. Banks have to get their money back everywhere in the world."

When one member of the cooperative tour group asked whether he was a socialist and whether the co-op identified as socialist, Castelano said that each member of the co-op would have to be asked that question. Witty, cocky and unapologetic, he also said: "I am Cuban and I defend Cuba."

In November, 2017 the co-op had plans to open a new restaurant in another part of city.

CIMEX Our second restaurant run by a worker cooperative-in-training was Cimex, in the beautiful mountainous area of Matanzas. On the way, we saw groves of mango, and palms in one of the most fertile parts of Cuba. The restaurant was part of the Monserrate complex, a recreation park, museum and restaurant. There were beautiful views all around, including in the cooperative restaurant. The complex is owned by the government and is a state-run facility. The current restaurant manager was being trained in the new system. The restaurant is expected to be a co-op at the end of 2017. The salary for co-op members is $400 CUP per month. The manager's challenge, he said, is to keep a meal affordable to all, with a menu that must include a basic three-part meal (with a drink) at a low price. This will be subsidized by the state.

Our second restaurant run by a worker cooperative-in-training was Cimex, in the beautiful mountainous area of Matanzas. On the way, we saw groves of mango, and palms in one of the most fertile parts of Cuba. The restaurant was part of the Monserrate complex, a recreation park, museum and restaurant. There were beautiful views all around, including in the cooperative restaurant. The complex is owned by the government and is a state-run facility. The current restaurant manager was being trained in the new system. The restaurant is expected to be a co-op at the end of 2017. The salary for co-op members is $400 CUP per month. The manager's challenge, he said, is to keep a meal affordable to all, with a menu that must include a basic three-part meal (with a drink) at a low price. This will be subsidized by the state.

The food was very good and they had a vegan meal. Theirs was the best pina colada in our travels.

La Casona de 17 Cooperativa

The La Casona de 17 Cooperativa (The Big House) is located across the street from Edificio FOSCA, the tallest building in the country. On the 33rd floor is a skyline bar and restaurant with overpriced food and drinks, but they come with spectacular 360 degree views of Havana. The building houses many foreign worker visitors to Cuba, has a ground floor store and is around the corner from the Hotel Naccional. One may not be able to afford to eat at one of the restaurants in this building called by the UN one of the 7 wonders of Cuban civil engineering, but one can eat a very nice meal at the cooperative across the street.

La Casona was the very first cooperative created by Cuba’s Ministry of Tourism, said Yadira Alfonso, Secretary, who was at the restaurant when we dropped by after leaving Fosco and noticing that it was a cooperative. She explained that the Ministry provided the building space and the opportunity for the workers to develop a cooperative workplace that they managed.

"This is a new movement for the country," Alfonso said. "We feel well supported by the Minister of Tourism. “

The location is advantageous for attracting a lot of national clients, she said, such as government tour groups, as well as local regulars. Thirteen people got together to found the cooperative, which manages the “house,” which has a fully equipped meeting room upstairs that is rented out for 20 CUC/hour. The house also serves as a nightclub in the evening. They call it “a service co-op.” The original founders – Alfonso was one of them – recruited seven more and on March 26, 2014 the co-op was established with 20 members. Each paid $5,000 CUP membership fee. The ministry trained them for three months, said Alfonso, who is also the barmaid. Her shift is 8 pm to midnight.

Thirteen people got together to found the cooperative, which manages the “house,” which has a fully equipped meeting room upstairs that is rented out for 20 CUC/hour. The house also serves as a nightclub in the evening. They call it “a service co-op.” The original founders – Alfonso was one of them – recruited seven more and on March 26, 2014 the co-op was established with 20 members. Each paid $5,000 CUP membership fee. The ministry trained them for three months, said Alfonso, who is also the barmaid. Her shift is 8 pm to midnight.

Membership has grown to 43 members or “socios” who receive an “anticipation” of 3,000 to 5,000 CUP/month after a 10 per cent tax and lease fee. Average income of “socios” (partners or business associates) is 150 to 500 CUC/month. ("The law of the co-op: The more you work, the more you make,”Alfonso said.) In addition, she said they earn 6 to 7 CUC/day from tips, which are pooled and shared monthly. The union teaches new members about co-ops.

Social security for each worker is also deducted. Thirty percent of costs after expenses is set aside in a reserve fund. Each member is voted in by the Assembly and has a 3-month probationary period, Alfonso said.

In addition to members they contract electricians, drivers, security, accountants and laundry workers. The co-op rents furnishing from the state, which pays for repairs because they rent.

Our waiter was quite attentive, taking special care to see that everyone was satisfied. I certainly was; the vegan meal was great.

I asked him what he liked about his job in a cooperative. "Here, it is a relationship,” he said. “Other places, it is a job.” He added: “It is nice to see the people satisfied with my attention.”

Asked what is the best part about being in a cooperative, Alfonso replied: "We get to make the decisions."

SCENIUS Cooperative

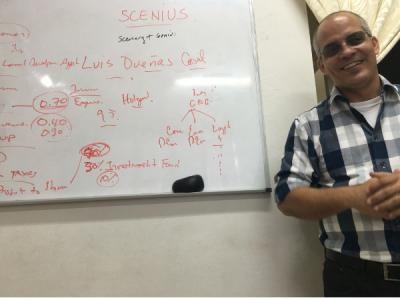

A carport in a nice home in the Miramar section of Havana has been transformed to the employee lounge for the Scenius accounting cooperative. Posters explaining the International Cooperative Alliance’s seven cooperative principles are fastened to the wall. Small round white tables dot the open air carport and plastic patio chairs surround the tables. A man and a woman sit smoking a cigarette when we arrive, obviously on break. Two shiny electric bikes parked in the driveway stand out and grab our attention, somewhat out of place for the Cuba that is surviving without new and on fixing and rehabilitating old cars, appliances, furniture and wood planks. I am excited because the ICA cooperative principles here are the first evidence we’ve seen in all the cooperatives that we visited of the cooperative principles.  This is the home of the co-op’s president, Luis Alberto Duenas, one of three partners who in 2015 helped to form Scenius, the second self-initiated co-ops started in Cuba that we have been exposed to. The name is a cross between “scenery” (as in view, natural features and landscape) and “genius.” It is the name that best fit what the cooperative wanted to be about, Duenas said. Scenius is one of six accounting firms in all of Cuba: four in Havana and two in Santa Clara, a 2 ½ hour drive away. They became a cooperative because that was the only way for professionals to be self-employed, said Duenas, an engineer who learned English in the Merchant Navy. We sat in plastic chairs in the living room. A receptionist sat at a desk to one side, and later served us Cuban coffee.

This is the home of the co-op’s president, Luis Alberto Duenas, one of three partners who in 2015 helped to form Scenius, the second self-initiated co-ops started in Cuba that we have been exposed to. The name is a cross between “scenery” (as in view, natural features and landscape) and “genius.” It is the name that best fit what the cooperative wanted to be about, Duenas said. Scenius is one of six accounting firms in all of Cuba: four in Havana and two in Santa Clara, a 2 ½ hour drive away. They became a cooperative because that was the only way for professionals to be self-employed, said Duenas, an engineer who learned English in the Merchant Navy. We sat in plastic chairs in the living room. A receptionist sat at a desk to one side, and later served us Cuban coffee.

The co-op first made a proposal to the local government in 2012 to create a worker cooperative “to provide support for cooperative development – all kinds of support for small businesses like IT, legal services, human relations, business support and accounting,” Duenas told us. “People don’t know much about business planning. We wanted to help with that. We help people understand the new rules and regulations, and the tax laws, etc.”

Worker cooperatives are still very new to Cuba. The government, after an attempt during the special period to encourage entrepreneurs to help the economy, wants to switch focus to cooperatives, according to discussions we heard from different scholars. Duenas took the lead in trying to take advantage of the new regulations, and in helping others.

More than two years later, in 2014, the government finally came through. It had taken 26 months to approve their application, but they would only allow the co-op to offer accounting services. The accounting company has an economics (accounting) department and a commercial (marketing) department. He believes the government did not approve the other areas of work because they don’t “appreciate the need yet.” A hundred percent of their clients are “state entities.”

After about 18 months into the business, the work and the need for workers had skyrocketed.

“Now we have 200 associates and counting,” said Duenas. “Government entities lack accountants so there is lots of demand. Every time the government has a new need for accountants, we add more accountants.”

“Why don’t we do work for private businesses?” Duenas asked, anticipating the question from the group. “They do not want outside accountants looking at their books. They prefer undercover accounting. Their transactions are in cash and they want to avoid taxes.”

Scenius started out working with start-up co-ops, but currently they don’t. “They could pay us at first but now don’t want to pay our prices,” he said.

However, Scenius does offers free services to fellow cooperators.

“It’s part of our social responsibility,” he said. “We help groups that want to be co-ops develop their proposals and give advice. We do that for free, but not the accounting.”

All of the co-op members are graduates of the University of Havana or other universities in Cuba. Sixty percent of the 200 members are women.

“Our accountants earn ten times what state accountants earn,” Duenas said. They also have “indirect associates” – the administrative and marketing staff – and all are members of the coop. The average age of the cooperative membership is about 45 years old, he said. They are working on attracting more young people.

In addition to helping to advise other cooperatives, Scenius’ sense of social responsibility is “our members/associates attending meetings and participation and attending the General Assembly, the final deciding body for cooperative policy, pay and other regulations. Members are not paid to attend meetings and most meetings are held after working hours. People do it to be good team players and because participation is part of being a cooperative, and is part of learning together, sharing information and giving back.” Because Scenius is a co-op, it understands what the members of all cooperatives must undergo: Everyone must be taught about working in a cooperative.

Because Scenius is a co-op, it understands what the members of all cooperatives must undergo: Everyone must be taught about working in a cooperative.

“The main challenge for people in cooperatives is to change from thinking like a worker to a manager. Workers just do as they are told and earn their salary. They are not used to making business and money decisions, or thinking ahead and planning. They can’t always understand the financial part of the business. People have to learn what is an enterprise, what is sales and income, what laws pertain, etc. Training is needed. We are interested in training. We see training as a problem and need.”

“We educate people first for the economic point of view, but also promote social activities. They have lunch included at the General Assembly. We celebrate birthdays. Our people are focused on working and separating our cooperative from the competition. We have monthly meetings with each client to make sure we are fulfilling our contract. We review what we have done and what needs to be done and how we are doing. We keep good relations with our clients and keep communication open. We also have quality control policies and measures and pay an associate [more than the rest of us get paid]. Every three months we review as a group. Every 3 months we have a general meeting and then the annual General Assembly."

Social security and health insurance premiums are paid for members. This is included in Cuba’s Regulation #306" [#305 is the incorporation of cooperatives and self-employment, Regulation #306 is about participation of these new structures in the social welfare system]. “We pay into the system, each can choose on a scale of costs and services.”

After 13 months of working for the cooperative members qualify for share and dividends/bonuses. The co-op is renting a vacation house by the year so all associates can take vacation at the beach sometime each year. They bought 3-4 electric motor bikes for employees to get around town in. Being a member of an accounting co-op, Luis readily broke down the co-op’s finances to the tour group.

Being a member of an accounting co-op, Luis readily broke down the co-op’s finances to the tour group.

“From gross income (revenues) we pay 10 percent of total sales to the state for income tax and 1 per cent to local government for local development,” he said. “Then we take out all expenses. We must pay 10,000 CUP to government for each partner. Then from net revenues, pay another 45 percent in revenue taxes. Up to 70 per cent net profits can be distributed to the associates/partners/members, and 30 per cent goes into an investment fund that is retained for the co-op. There are no personal income taxes to pay – these are all corporate or taxes the enterprise/the co-op pays,” he said.

Agricultural co-ops have a different relationship with the government – they pay lower taxes and have The National Assembly of People’s Power to represent them and lobby for them. “Non agriculture co-ops are starting to get more power and their own associations,” he said.

Co-op members made some financial mistakes that they learned from.

“The first year the members voted to distribute all the money they had, all the net profits and so had no reserves,” he explained. “But now they realize they need reserves to cover costs of finding new markets and looking for new options, etc.” He expects the vote will go differently at the next General Assembly. They are learning what it means to be a partner and associate rather than a worker. They see the results of competition and that when they have reserves they can explore more opportunities.

Membership meetings take place every three months, renting space to fit everyone. Every team of 15 discusses proposals they want to make at the General Assembly. “We operate in groups/teams working together and discussing issues,” Duenas said. “Then at the General Assembly we create and agenda based on all the proposals, especially about distribution, etc. Then we meet and make policy decisions. Everyone understands how to read the income and expense statements, etc., because we are accountants, so it is easy to run the company as a cooperative. We understand a lot already. “

The board of directors is appointed by the General Assembly. The organizational structure is President and board of directors, then General Director, Duenas said. There are three departments: Commercial (marketing etc.), Economy (accounting and professional services), and logistics (office management). The co-op uses simple majority: “Our decision-making is 50 percent +1,” he said.

Duenas said the co-op is preparing for the day when there are many more international businesses in Cuba.

For more information, please see part of Duenas’ presentation to the group in this video.

El Bambu Centro

El Bambu Centro is a worker co-op in training in an alley in the Chinatown area of Havana. The co-op-to-be, a “factory” with several rooms stacked with bamboo and grey walls decorated with pictures of revolutionary leaders, flags and slogans. They make furniture, vases, jewelry and other items such as incense burners, all out of bamboo. Because the co-op is a workforce development project, they do not pay the state rent, said the president Carlos, whose last name I didn’t get. He spoke through our interpreter, Raul Diaz Pomares. The bamboo is provided by a member who has a farm, he said. Three other members on the farm are the co-op’s partners. The group provides shelter, education and training for young people. They will be the co-op’s members. “Succession planning is the sense of life for us,” he said.

The group provides shelter, education and training for young people. They will be the co-op’s members. “Succession planning is the sense of life for us,” he said.

Six young people compose the co-op-to-be and make collective decisions. El Bambu Centro works with the Cuban Higher Institute of Design.

Carlos, whose face lit up as he talked the work, said they have learned not to focus on just one product. They charge 8 to 15 CUCs for a vase. “We are well paid,” said Carlos, whose smiles and friendly and serious demeanor, said that he enjoys the work. Their salary, 10,000 CUCS, is 20 times the national average, said Al Campbell, an economist who frequently travels to the island and has written about Cuba and edited the book, Cuban Economists on the Cuban Economy (Contemporary Cuba). Their plan is to sell locally and work with local cooperatives – their neighbors and local enterprises. They have applications submitted to become a worker cooperative, but approval takes a “long time,” he said.

The president was talking about avoiding a lesson that Scenius recently learned: not to pay themselves too much money in the beginning, and saving some for the co-op's development.

He also said that the co-op has no plans to ship their wonderfully artistic goods overseas.

He also said that the co-op has no plans to ship their wonderfully artistic goods overseas.

Carlos said they are learned three main things:

- “The market that saves us is local,” he said.

- Deal in direct payment without debt.

- Have “friendships” with other co-ops, such as the farm that supplies the bamboo.

We also were surprised to learn that they train a different group of students from Virginia every six months.

Carlos’ wife bought sweet tea for us, and just about everyone came home with some of the unique designs from Bambu Centro.

We were exposed to ideas that might benefit the development and operation of worker cooperatives in the U.S. For example, the way the construction cooperatives uses professionals to help with individual members develop and make clear linkages to team-building. In addition, the co-op’s use of recycled goods to provide benefits to its members beyond pay to allow works to experience the cooperative process. Another example is the 12-hour work day with alternate days off. Still another could be the use of co-ops as an economic development measure by providing training for young people to become members of co-ops with the help of government aid.

In addition, I believe that our worker cooperative movement may be able to offer some perspectives on worker cooperatives since we have almost a 50-year history operating them in this capitalist country, mostly without government support. It makes for an interesting contrast: the development of worker cooperatives in a supportive environment from a socialist government, and those worker cooperatives which managed to survive in a “business-is-war” capitalist environment with little or no help or even understanding from the government. In socialist societies, the means of production – land, water, utility infrastructure, transportation, key factories and businesses, etc. – are owned, not by private companies, but by the government to ensure that they benefit the majority of the people. In a capitalist economic system, the means of production are generally owned by private companies and individuals with some exceptions like municipal water companies, but increasingly utilities such as water and electrical companies are privately owned or are being considered for privatization.

As the Union of Radical Political Economists steering committee member Al Campbell (who was part of the tour) suggested in his remarks at the University of Habana, perhaps the U.S. worker cooperative movement could utilize some of the strategies of the Cuban government and the way it supports worker cooperative development.

Some years after Cuba’s successful revolution, the state believed it should own most production. The USSR was Cuba’s main financial and political support, and development of Cuba went the way of the Soviets, according to officials at the Instituto de Filosofia (Institute of Philosophy).

"With economic aid came the economic system,” said Humberto Miranda, a member of the Instituto de Filosofia. “It was one party…a very centralized system. It was what was needed at the time.”

According to Miranda, cooperatives had been discredited by what happened in China and in Russia. With state ownership, the thinking was that workers were able to have self-management without cooperatives.

“The dream of socialists was cooperatives,” Miranda continued. “But in Cuba, workers got self-management without co-ops. Workers were to gain skills. "

In 1959, at the time of the Cuban revolution, 81 per cent of the land was in the hands of private persons – owners of sugar plantations and others. Land was nationalized and agricultural cooperatives formed. As already mentioned, agricultural cooperatives are by far the oldest and largest cooperatives in the country.

Co-ops manage 70 per cent of the agricultural land and produce 75 percent of the food for internal consumption, according to Beatriz Diaz, of the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences, or FLASCO. Much of the production is organic. There are 383 nonagricultural cooperatives, she said.

(For more information, please see Camila Pinero Harnecker's video in English on “Cooperatives in Cuba: Their contribution to Cuba's New Socialism,” and Euclides Cata and Osnaide Izquierdo’s “Cooperativas no agropecuarias. Desafíos e impactos para el desempeño socio-productivo y el desarrollo local en el contexto de Actualización del Modelo Económico Cubano”/"Agricultural Cooperatives: Impact and Challenges for Social and Local Development in the Present Context of the Cuban Economic Model.")

After the USSR collapsed and Cuba lost economic aid, the Cubans suffered and went through what is called the Special Period. During this time, economic support from the USSR disappeared leaving the people without income or jobs and was a particularly tough economic time. The Cuban people also had to survive the hardships caused by the U.S. economic blockade which made it difficult to import other goods that the country needed.

Worker cooperatives started to be developed in 2012 when legislation was introduced to convert state enterprises to urban cooperatives. The state provides financial assistance in the way of free rent, or subsidies per passengers in the transportation co-ops, and sets guidelines for salaries.

To start a co-op one must go through the municipality and the nation, and must also get the approval of the Government ministry that oversees the industry sector (such as transportation, construction, etc.). Although worker cooperatives are a new development – about five years old – some of the understanding, passion and hard work for cooperative work, teamwork and solidarity appear to be far advanced.

Although worker cooperatives are a new development – about five years old – some of the understanding, passion and hard work for cooperative work, teamwork and solidarity appear to be far advanced.

Saving the Economy - Muy Complicado

Since the USSR pulled out, Cuba has been trying to redefine its economy. First, there was an attempt to encourage more private businesses. The challenge is to do that and maintain the socialist ideals of the country and not allow U.S. money to destroy the gains of the revolution. Second, the Cuban government is training many workers to be cooperators in charge of their own group businesses.

Hopefully, the North American worker cooperative movement could help their Cuban comrades in some ways that do not violate U.S. or Cuban laws. For example, as brought out in the conference, Cuba is not a part of the International Cooperative Alliance or CICOPA, the international worker co-op organization. The country could benefit from the experience of the North American worker cooperative movement, and all manner of assistance is probably something that they can use. After all, the U.S. worker cooperative movement has at least 48 years experience as worker cooperatives, with veteran co-ops such as The Glut Food Co-op in Mount Rainier, Md. (just outside of Washington, DC and The Cheeseboard Collective in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Center for Global Justice has organized a second worker cooperative-focused educational tour for June 18 - July 1. For more information, see the link and/or contact Cliff DuRand at cuba@globaljusticecenter.org.

Cliff DuRand, Jessica Gordon Nembhard and Xianyue “Jenny” Li contributed to this article.

[Correction: A previous version of this article stated that the Cuban National Assembly sets policy for co-ops, rather than the Cuban General Assembly. GEO regrets the error and thanks the attentive reader who pointed it out. -ed.]

Go to the GEO front page

Citations

Ajowa Nzinga Ifateyo (2017). Visiting Worker Cooperatives in Cuba: Muy Complicado: Most are New, Government-Initiated, and Complicated. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/story/visiting-worker-cooperatives-cuba-muy-complicado

Comments

Amina Mama

January 6, 2020, 7:01 pm

wonderful teaching resource for teaching course on globalization, gender and culture in feminist, Southern perspective.

bobstone68@gmail.com

May 16, 2023, 12:52 pm

This is by far the best piece I've ever seen on Cuba's new urban cooperatives! It shows the way for cooperativizng economies! Thorough & beautifully written, this should be widely available in the US worker coop community! Makes worker coops global models. Many, many thanks, Ajowa!! Keep up the great work!!

Add new comment