By Joe Marraffino, Arizmendi Development and Support Cooperative

Since the mid-1990s a group of worker cooperative organizers in the San Francisco Bay Area has been developing a new model for cooperative development. Our organization, the Arizmendi Association of Cooperatives, is a network, incubator, and technical assistance provider that is owned, governed, and funded by the member workplaces it creates and serves. Our primary activity is to replicate and offer continuing support to new retail bakeries based on a proven cooperative business model.

This new model seeks to work around some barriers to the growth of the cooperative movement. One of these barriers is the tendency for cooperative development work to be done in contexts that have high rates of failure. When the Association is ready to develop a new bakery cooperative, we find a new site, draw new capitalization loans, recruit new worker-owners, and face the risks that any new enterprise faces. However, these risks are reduced by what is not new: the enterprise adapts the same business plan that existing member bakeries have used, it offers a tested product line using the same recipes, it has a similar name and co-advertises to nearby markets, it uses proven governance structures, and it shares the cost of support services with other members. It even houses some of the same sourdough starter culture. Building on these similarities, the new worker cooperative bakery will cost less, start faster, and be more resilient than an unprecedented business. This initial advantage is reinforced by a network of similar businesses offering mutual aid, and by enduring technical assistance.

Another growth barrier of the worker co-op movement this model addresses is the limited and irregular availability of funding for co-op development organizations. Development funding for the Association comes from member workplaces who contribute a percentage of their net income as membership fees. If the workplace is not profitable yet, they pay nothing for membership but still receive full technical assistance services. As workplaces mature, the income to the Association increases, and with it the funds available for development increase. The income projection for the Association curves upward: the more profitable businesses we develop, the more contributed fees are available for development. The Association has developed three businesses in a decade without any external philanthropic contributions, and is poised, now in 2009, to develop another.

As a member of this association, I'm happy to describe some of our model here, with the hope that others in the worker cooperative movement may find elements to borrow.

The Origins of the Arizmendi Association

In San Francisco during the 1970s a wave of small worker cooperatives self-organized, and several local organizations formed to develop and support democratic businesses. The InterCooperative, a regional network, began publishing a directory listing scores of cooperative and collective businesses. The Alternatives Center published a newsletter on cooperative activities, and sold technical guides and videos on cooperative process. The Democratic Business Association offered legal and organizational consultation. Some new cooperatives branched off from existing ones. The Cheese Board Collective, a retail artisanal cheese and bread store cooperativized in 1971, and then split the organization into two internal cooperatives when their pizzas sales grew formidably. During its history members left and opened a cooperatively-run restaurant, a juice bar, and another cheese shop. With each of these divisions, the Cheese Board lent money to the new developments, but did not hold equity in them or require any future organizational relationship to them.

Few of the small cooperative businesses had the resources to pay for technical support. By the mid-1990s only a handful of co-ops listed the 1970s directory were still operating, and few of the support organizations were active. During this period, there was renewed interest in organizing cooperatives in the Bay Area. A new regional federation, the Network of Bay Area Worker Cooperatives, began to meet informally. Women's Action to Gain Economic Security (WAGES), a nonprofit business incubator, was formed (See article on WAGES in this issue). In 1995, the Arizmendi Association of Cooperatives, a cooperative corporation, was founded. The organizers of the Arizmendi Association were three alumni of previous support organizations, and included a veteran member of the Cheese Board.

The organizers sought to overcome some of the obstacles made visible by previous worker cooperative development projects. One was the negative feedback dynamic of a fee-for-service income model: the more a cooperative needs help, the less they are likely to pay for it and get it. This influenced their strategy for membership and dues. The organizers also realized that attempting to develop an expertise in many different kinds of businesses was labor intensive and increased the chances of failure. They decided to choose a thriving worker cooperative, to become experts in that one business model, and to replicate it many times. In doing so the development and support services would get more efficient as more cooperatives were developed, not less, as they would if every business were very different. With that in mind, they recruited the help, and founding membership, of the Cheese Board Collective.

In the 1995 the organizers approached the Cheese Board with the idea of helping to create "the largest possible number of decently-compensated work opportunities in democratically operated businesses that function as part of an interdependent economic framework." With great generosity, Cheese Board Collective members offered their recipes, their organizational structure, startup funding, and use of their name in marketing. Over a decade later, when customers realize that the Arizmendi Bakeries are connected to the Cheese Board, the bakeries enjoy an immeasurable boost in value and legitimacy due to the "mother" store's reputation.

The Replication Cycle

The replication process can best be seen by looking at the structure of the whole organization. The Arizmendi Association of Cooperatives is a cooperative corporation with two membership classes. At present there are four corporate members: the Cheese Board, and three "Arizmendi Bakery" replications of the Cheese Board model that the Association developed. These businesses are independently owned, and are members of the Association on a voluntary basis - however, the use of the name Arizmendi and the right to trade secrets, such as recipes, are restricted by contract in the event a business should want to leave the Association. Each corporate member elects two delegates to sit on the board of directors of the Association, which we call the Policy Council. The Policy Council determines the aims of the Association, the level of fees required, and the services the Association will provide to its membership. The other membership class is for an internal staff cooperative known as the Development and Support Cooperative, or the DSC. This group also sends delegates to the Policy Council.

Corporate members contribute a portion of their income to the Association, the formula for which is set as a percentage of net profit for the first several years. This is a relief to the newborn cooperative when it has no profit in the first year or two, and also an incentive for the Association to create businesses that will become profitable as soon as possible. As the business matures, the formula transitions to a percentage of sales, modeled loosely on a franchise relationship. Often this means that the cooperative pays least when it requires the most help and more when it requires less help.

Annually the Policy Council mandates and budgets for the activities of the DSC. The DSC provides bookkeeping, legal aid, new member educational workshops, facilitation and conflict resolution services, organizes cross-Association communication, and contracts with outside professionals to offer the members tax advisement and other professional services. (Because of its special role as the original business model, the Cheese Board's fees and the services they use are negligible compared to the other members.) At present, the DSC's total labor hours hover around the equivalent of one full-time worker, currently divided by four members. While there is no fee-for-services equation to the fees contributed, there is also no limit to the intensity of services a member might request. A disproportionate amount of the budget might be used to help a struggling member if needed. Barring such a crisis, the Policy Council budgets for a surplus after offering support services. This surplus is used for another of the organizations aims: job creation.

When the Association is ready to develop a new cooperative, its staff enlarges to include trainers from the existing member bakeries. These trainers work in the new store for as much as six months, in order to communicate skills and demonstrate democratic communication to the new workers. At the end of this period, the trainers withdraw to their home bakery. The Association pays both for this training and for DSC development services, such as facilitating the work of an architect and contractor, negotiating loan and lease terms, incorporating the new cooperative, recruiting members, and offering financial and organizational training. The Association also puts in place a Contract of Association defining the relationship between the new and existing cooperatives. Finally, the DSC facilitates the lending of startup capital to the new cooperative. The debt will not be incurred by the Association, but by the new, independent business.

Starting with only the Cheese Board and the DSC, the Association has replicated the business model three times in a decade. It accomplished this without the philanthropic grants; though it did receive some startup money from the Cheese Board and unsecured loans extended in good faith by individuals in the Cheese Board's community. Each development cycle has exhausted surpluses generated by member fees, and a fallow period without development activities has followed. These fallow periods will diminish as the Association develops more members.

[Article continues below diagrams]

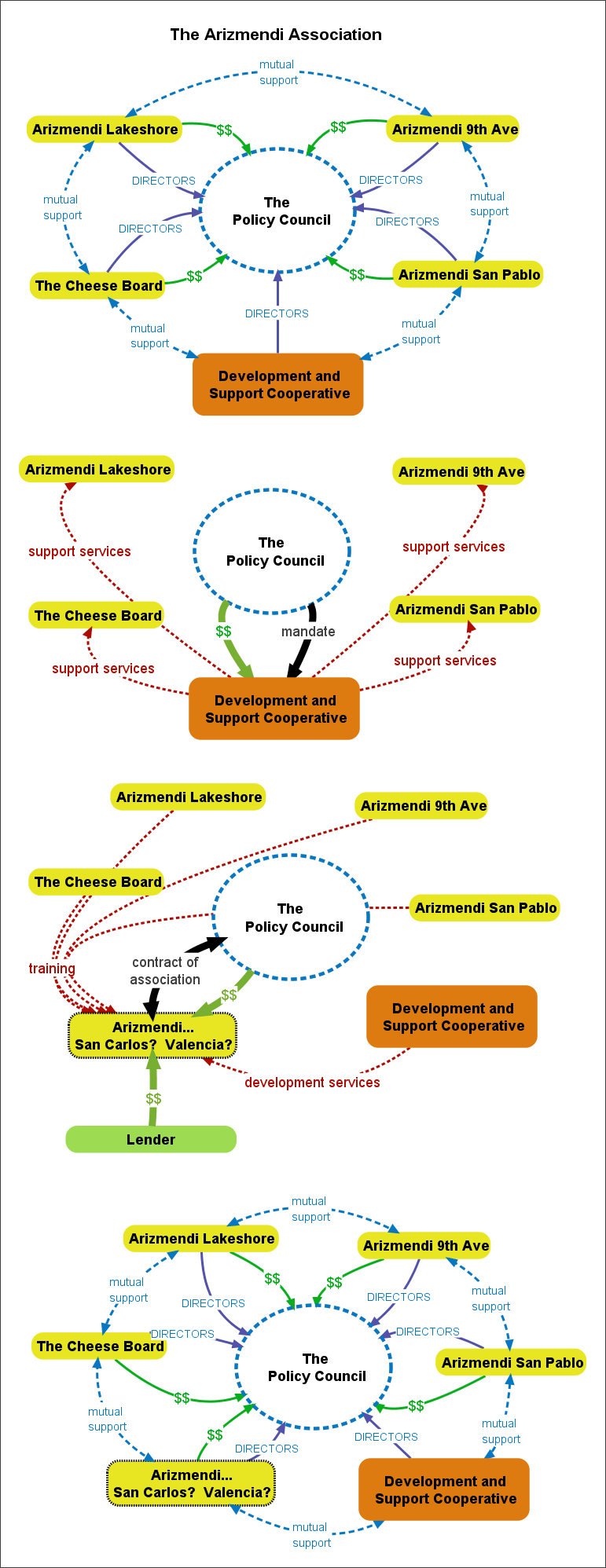

The Organizational Structure of the Arizmendi Association and the Cycle of New Co-op Development

1. The organizational structure of the Arizmendi Association. There are four bakeries in the Association. In addition there is an independent Development and Support Cooperative (DSC) that provides legal and business services for the bakeries and plans and organizes new startup bakeries. Each of the bakeries and the DSC elect members to the Policy Council which manages the Arizmendi Association.

2. The relationship between the policy council and DSC. The Policy Council mandates the goals and policies for the services offered by the DSC. The DSC provides legal and business services to the bakeries.

3. Starting a new bakery. The Policy Council decides to start a new bakery providing some of the start up cost and a contract of association. The DSC organizes the startup. Startup activities include such activities as choosing a location for the new stores, arranging for startup capital, and coordinating training of the startup co-op?s members. Established bakeries provide trainers for the new co-op.

4. The new bakery joins the Arizmendi Association and elects members to the Policy Council.

In the future, there are different ways the Association could develop. While this structure has done well for us, it has also been a creative experiment adapted as needed. Our current strategy is to saturate the Bay Area with the one business model, as it is the most efficient use of our still-limited resources. However, the market for neighborhood bakeries is not unlimited. Before we are able to sense such a limit, the member bakeries themselves will probably choose to restrict replication, in order to protect their perceived territories. Some members envision selecting another business model to replicate. Others envision reaching a critical mass of bakeries such that we might create jobs vertically - a flour mill, for instance, or an equipment maintenance team, or even a lending institution to offer capital to new developments. In another vision the Association would replicate itself and begin to create Arizmendi Bakeries in another city ? but because the efficiency of our support services increases with our density, and because trainers for new developments have historically worked part-time in their own cooperative and part-time in the new business, such distant start-ups would pose new creative challenges.

Steps for Replicating a Worker Cooperative using the Arizmendi Association Model

Our Association's steps to starting a cooperative differ in some ways from those outlined by popular worker cooperative organizers' guides. Perhaps the most significant difference is that much of the groundwork for the new cooperative is laid before members are recruited. This would appear to contradict the need to inventory members' skills, objectives, and economic needs to assure that the cooperative will benefit them. To make this leap, we assume there are pools of potential members whose abilities and needs match those that the cooperative requires and offers. Because of the density of our urban area and the high competition for decent-paying food industry jobs, this leap has been easy to make. While it is still important to include founding members of a new co-op in decision-making to foster group cohesion and democratic initiative, for the sake of efficiency the Association makes some of the early business decisions for the new co-op. For example, in our first replication founding members worked together to discover and negotiate for a location. In the development now underway, the location will be established before members are recruited.

Below, our replication process is loosely laid out in steps, intended as a rough guide for those who might like to use our model. The process is based on a long-term vision but has evolved improvisationally over time. Our cooperative association model will inevitably be refined according to the needs and desires of the member cooperatives that govern it.

1) Establish an organizing group. This group will facilitate replication, but will not necessarily own the developed cooperative. In our current case the organizing group, the DSC, started as a volunteer study group. The DSC still works only part time on development, as our financial capacity to start a new business is not constant. One of the four of our current group has worked in a member bakery; the others have legal, financial, and organizational expertise.

2) Choose a business model to replicate. This involves not only choosing the right cooperative business, but also convincing its members to allow you to replicate it. What's in it for them? Would the replication compete with their business? Would it increase their visibility and therefore revenue? Is there any financial return? In our case the Cheese Board had the financial strength to request very little in return. The creation of more democratic jobs did align with their values, and the Association can now offer support services to them, but their willingness was primarily an act of solidarity and generosity. For other replications, including future business models the Arizmendi Association may pursue, the organizers may not be so lucky.

The business model we chose has many good things going for it. One was that it entails a lot of customer service, an area in which worker-owners out-perform employees, often establishing lasting relationships with customers. The product is high quality and relatively inexpensive, helping generate a large customer pool by word-of-mouth. The model can be replicated many times in the Bay Area before saturating the market. Morning bakeries function as neighborhood civic spaces, which reinforces the community spirit of the collective. One downside was that sale of imported cheeses brings lower returns than bread, and requires more intensive training. Because of this cheese sales were all but eliminated in our replications in favor of pizza, bread, and pastries. Another downside of this business model is that it does not create a large amount of jobs. Each of the three Arizmendi Bakeries is owned by around 20 members.

3) Decide what relationship the new cooperatives will have to the older co-ops. Our model is described above, but our structure has not come about without some challenging questions. Who will own the replicated businesses and the debt of their startup loans? What will their relationship to each other be? How will the replication process be funded, and how can this funding continue or escalate over time? What incentive is there for the new co-op to stay involved with the ones that generated it?

The Arizmendi Association model uses the analogy of an "upside-down franchise." The new cooperatives stay involved because they are offered the kinds of services most efficiently provided centrally: financial, legal, educational, and other technical assistance services. The cooperatives govern and define these services, determining the rate of fees they contribute. Owned independently, the cooperatives are given the autonomy to adapt creatively to their needs. As owners of their own debt, they have incentives to make their business succeed. Meanwhile, non-debt development expenses are covered collectively by the Association and fees are contributed, in part, to perpetuate the development cycle. As more members come in, resources to create more members also grow.

4) Set up the "turn-key" operation. In preparing to open a new worker co-op, the Association incorporates the new co-op prior to recruiting new worker co-op members. Thus, members of the Association are temporarily also the membership and officers of the new co-op. They must find a site for the new business and acquiring capital from a bank or a group of individual lenders in order to buy equipment and renovate. Getting a bank to lend to a business whose real members are not yet known can be difficult, and because the Association does not own its member cooperatives, it has little collateral to offer banks as security. Our track record and the social missions of the lenders we have worked with have helped to overcome this obstacle. For a new Association without any track record, lenders within the worker cooperative community may be needed.

5) Recruit and train new workers. We recruit new workers during renovations about six months before the anticipated opening. The recruiting committee is made up of veteran members of existing bakeries. For the first months we do weekly organizational trainings, and several of the new workers are placed in internships at the existing bakeries. Working committees are formed during this time to do marketing, establish relationships with venders, and prepare other aspects of the startup. Once renovation is completed, new workers will train in baking bread for about two months before the store opens.

Our training team is made up of bakers from the existing member businesses. These bakers will work part-time at their home bakery and part-time in the new development. Having a pool of trainers available part-time every few years when development is in motion is a great resource, eliminating the need to hire an external team. The trainers oversee new members' work, working alongside of them for as long as six months. They demonstrate best practices in production, and set the tone of shop-floor communication and problem solving. We often think of this as a "sourdough" method of education: the culture of the veteran workers is the "starter" that creates the flavor and structure of the new workers' culture. Toward the end of the training period, the new workers will form a committee to recruit replacements for the trainers, who return to their home bakery.

6) Repeat. Every replication will teach valuable lessons about what to do and not to do. Make sure to have a good evaluation of the process which included the views of the developers, the training team, and the new cooperatives members. Consider the long term as you hone your process.

Challenges

It has been a slow journey. Originally, the organizers of the Association had hoped to develop a new bakery once a year. Instead it has been at around a quarter of that speed. Our model has been very resource efficient, but has a slow growth curve. For many years only the first replication was contributing significantly. The Association staff, the DSC, could only afford to work very part-time or as volunteers. A decade later, three member cooperatives are now contributing significant fees. As we grow into a more robust organization, our former lean years will seem more and more foreign, but for organizations following in our footsteps adaptations may be available to accelerate the development process.

Conclusion

The replication of the Cheese Board Collective model into three Arizmendi Bakeries (with a fourth in progress) has been successful. All of the businesses are profitable and have support services ready should they falter. The quality of the food is high, earning multiple critic and reader awards in the local press. The average labor compensation is almost twice the industry average. Worker turnover is low. The original generosity of the Cheese Board and the excellent business model they offered (which itself was refined over several decades) has helped put the Arizmendi Association in a good position. We will continue to replicate bakeries for the next several years, and when we reach a saturation point we will adapt and innovate.

Joe Marraffino is a cooperative organizer for the Arizmendi Association of Cooperatives, a network of worker-owned bakery cooperatives in the greater San Francisco region of California. He is also a worker-owner of the Arizmendi Bakery in San Francisco. He is a board member of the California Center for Cooperative Development, and former board member of the Network of Bay Area Worker Cooperatives. He has a Master's degree in Culture, Ecology and Sustainable Community.

When citing this article, please use the following format: Marraffino, Joe (2009). The Replication of Arizmendi Bakery: A Model of the Democratic Worker Cooperative Movement. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter, Volume 2, Issue 3, http://www.geo.coop/node/365

Add new comment