Worker Cooperatives in a Workless Century

We jumped over utopia and plunged straight into technological dystopia. We might have done things differently, but there are no do-overs. Where can we go from here? How do cooperatives, particularly worker coops, fit into this brave new emerging society of virtual techno elites ruling over a jobless future? Elites with access to capital and resources do not need coops. Coops are for the rest of us. Based on sharing resources and knowledge, coops are geared toward bridging the gaps, empowering people to collectively improve their lives and situations. In the face of the current crisis, will our society create new options for work for all people, or will future generations all too soon face the specter of total social disintegration?

Coops based on virtual technology will surely be an important sector of the cooperatives of tomorrow, but they cannot begin to address the needs of the vast majority of humanity being displaced, who need flesh-and-blood coops, producing real goods and services that real communities need to sustain life and a prosperous future.

Since the very beginning of the industrial revolution, the benefits of technological advances have always flowed disproportionately to those who control the technology, and today's technology is changing so fast now that confident economic planning is already beyond the powers of government planners. In the big picture, corporations, oligarchs, and virtual grifters rule the roost. Combined with globalization, we're in a world with increasingly fewer jobs, but still based on money and privatized ownership of the common means of survival. Are we doomed to an economy beyond work as we once knew it? Some people turn in despair to populist authoritarian leaders waving false promises, while others see technology itself as the enemy and turn to neo-Luddism.

When I was much younger, I began studying the history of worker coops, to try to understand why this society offered me so few economic options. I came from a family who knew only one way of making a living: find a job and become an employee. For my dad's generation, a good job meant decades with a stable income and retirement benefits. But by the time I was ready to go into the workforce, that social contract had expired. I had to work from an early age, and I didn't mind the work so much, but the rules of employer-employee were much too oppressive. Becoming an employee meant having to rent myself for certain hours in exchange for a wage. I wanted more control over my work life, where I knew I would be spending a lot of my time.

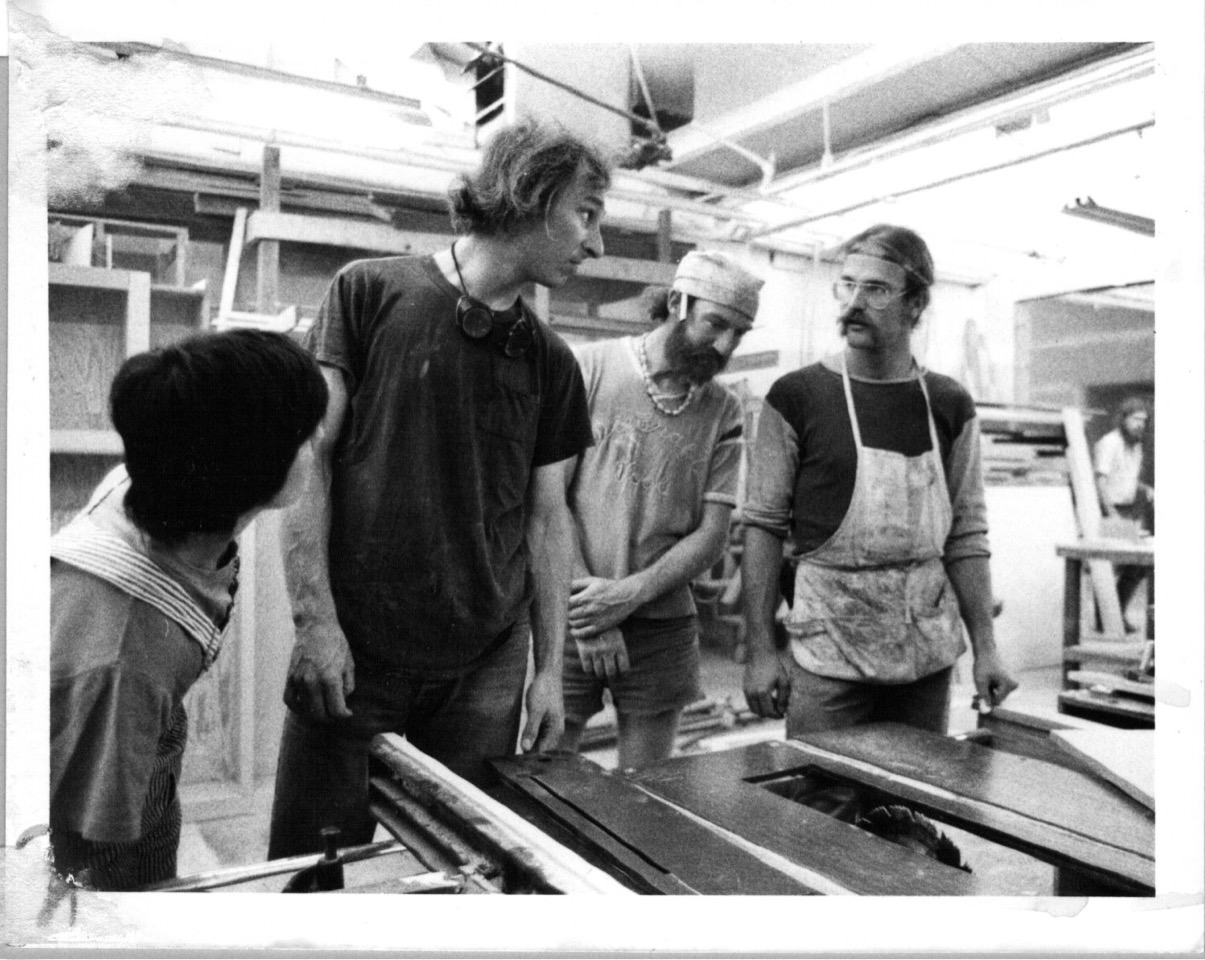

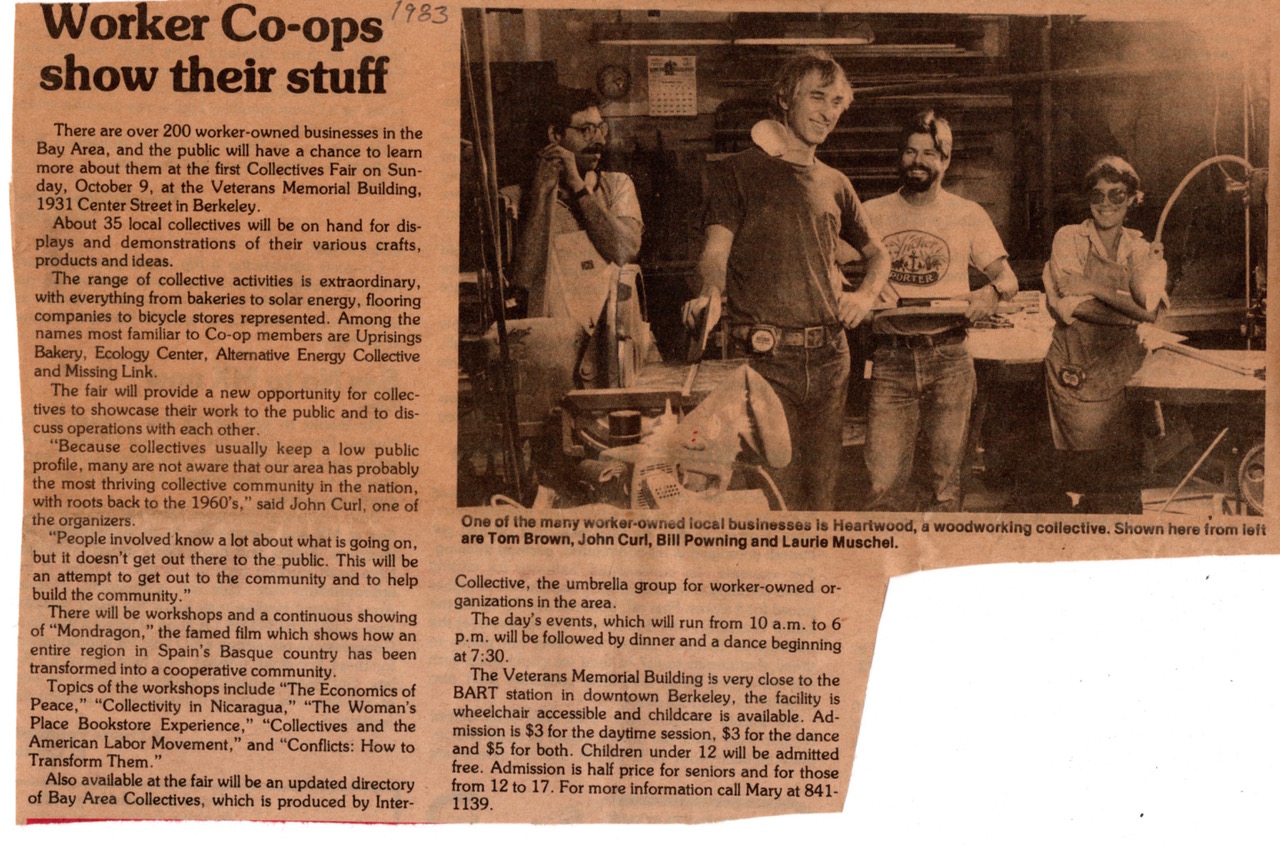

That led me to discover worker coops, and I wound up in Heartwood Cooperative Woodshop, where I worked for over 40 years until I retired. I thrived in that situation. I liked being my own boss, enjoyed working with the other cooperators, learned a skilled craft, and made a fair living.

Two hundred years ago, in the early 1800s, workers who were being displaced and impoverished by the technological developments of the early industrial revolution began organizing coops and founded the coop movement. Until then, as long as hand tool production and artisanal crafts had prevailed, the dominant technology remained comparatively simple, inexpensive, and accessible to almost anyone. But hand tools of course could not compete with factory production, so the new technology, which held the promise of increased prosperity for all, was instead forcing self-employed artisans to become factory workers, employees. Some artisans/workers responded by becoming Luddites and smashing machines. Others responded by forming cooperatives. The earliest worker cooperatives, in America as in Europe, were basically mutual aid associations, organized by the early trade unions, through which union members pooled their resources and opened coop businesses in competition with their former bosses. These worker coops met with significant success for decades, until the rapid development of technology and the inexorable consolidation of capital increasingly put whole industries out of reach of any group of cooperating workers.

The Age of Failed Utopias

Since the beginning of the coop movement, it has often been proposed that cooperative principles could be generalized to transform all of society, and early cooperators envisioned coops grown so ubiquitous that a cooperative society based on social justice would supersede capitalism. Cooperatives are very practical and utopian at the same time.

Worker coops formed a core part of both the early socialist and anarchist movements, both of which began in the 1800s in response to the industrial revolution. Early socialists promoted coops as embryos of a generalized socialist system. The aspirational vision of socialism promised a better world based on workers' control their jobs, social or collective ownership of the basic means of production and survival, combined with social planning. Socialists often conceived of socialism as the extension of democracy to the economy. Early communists held to a more extreme version. Nineteenth century anarchists, inspired by a vision of a self-organized cooperative society, were opposed to any hierarchy, authority, and large-scale government social planning.

But how can we get from a network of coops to a whole economic social system? Although most people are usually very cooperative, individualism and competition are also parts of human nature, and we each contain all those qualities to varying degrees. While more cooperative people tend to view this world as a shared collective project, more individualistic people tend to view it as a zero-sum game.

Modern capitalism and democracy both emerged from an age ruled by the divine rights of kings, and both began as radical utopian ideas offering the possibility of a freer and more just world. The wave of revolts that began with the American and French revolutions were fueled at first by ideas of the "natural" rights of all people. These rights became the foundation of the "free labor" needed by the emerging industrial capitalist system, but in the Americas were antithetical to the plantation slavery of the American South and parts of Latin America. At the time of the early industrial revolution, the violent excesses of the French revolution of 1789 was still a living memory and a cautionary tale.

The industrial revolution was the spark of economic/political transformative ideologies that would compete for dominance of the world in the following centuries: democracy, socialism, communism, fascism. These ideologies each offered aspirational visions. Democratic socialism offered the possibility of a more just society arrived at through peaceful and parliamentary means. But the failures of attempts to transform society through economic and parliamentary means, led some groups to resort to violence. Some anarchists focused on destruction, based on the conviction that out of the rubble people would rebuild a better world without hierarchy and authority. At the other end of the spectrum were the authoritarians, both communist and fascist. Russian Communism offered authoritarian social planning by a centralized elite in the supposed interests of the working class. Nazi ideology projected the cancerous vision of a master race utopia with enslavement for the rest of us.

All of these ideologies have been put to the test of the real world over the last two centuries, and none has emerged in practice able to fully deliver their promises. Today the ideas of democracy and democratic socialism appear to me to be the only practicable ideologies left standing.

The most extensive social planning of a socialist cooperative society took place in the former Yugoslavia, which organized a successful Self-Management/ Market Socialism system between 1950 - 1980, until it was dismantled by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, finally disintegrating in 1991 into civil war among ethnic groups, and the finally dissolution of the nation of Yugoslavia in 2001.

But cooperatives are beyond all of these ideologies, because coops succeed on their own terms, whether or not they are part of a larger system.

The other side of technological dystopia brings us back to the source, the real physical world, the land, the peoples, communities working together — all our sisters and brothers in this world of flesh and blood — toward a better today and tomorrow.

Searching for role models for success of the coop movement in this technological dystopia, we would be well advised to emulate the traditional economic structures of the Indigenous people of the Americas.

Cooperation, reciprocity, and sustainability in balance with the natural environment have always been the basis of the wisdom of Native lifeways. In the Indigenous world, all is on a human scale, instinctively democratic and egalitarian, and community is at the heart of it all. Native traditions are antithetical to regimentation and mass production. Coops among Native people in both North and Latin America today, are still mostly coops of individual producers and extended families: crafts, hand production, art, farmers, fishers, beekeepers, weavers, potters; coops providing supplies, resources, product distribution, social services and healthcare.

For the generations of millions of young people who will be trying to make a good life in a jobless future, society and its laws and customs need to promote cooperatives of every type.

The following three cooperative projects are alive and active today, and each one indicates a possible successful direction for the movement in the coming decades: Tosepan, The Intertribal Buffalo Cooperative, and the new Constitution of Nepal.

Tosepan

Tosepan is an Indigenous community coop with 35,000 Nahua and Tutunaku members in 430 villages in 29 municipalities in the Sierra Norte mountains of southern Mexico. Comprising a network of eight cooperatives and three civil associations, La Unión de Cooperativas Tosepan Titataniske (“United We Will Overcome” in Náhuatl), founded in 1977, is dedicated to improving the lives of its members through constructing a holistic, sustainable, and democratically-controlled local economy rooted in indigenous culture and knowledge, promoting organic ecological farming, natural building, local healthcare, decentralized renewable energy, and local finance. The Tosepan coops promote dignified livelihoods and ecological security by helping their communities together secure their basic needs. Tosepan has successfully opposed globalization and resisted corporate development projects including a Walmart. Their projects include agroecological farming, both for community subsistence and for sale (primarily in local markets), of organic coffee, pepper, sugarcane, corn, beans, vegetables, allspice, melipona honey; small-scale, community-based eco-tourism; natural building using bamboo, adobe, and other local resources, incorporating solar dehydrators and water harvesting; providing local health care, with a focus on prevention and traditional herbal remedies; decentralized renewable energy with a goal of total energy sovereignty; and a cooperative bank for local finance to support the functioning of the entire ecosystem of Tosepan cooperatives.

Intertribal Bison Cooperative

The Intertribal Bison Cooperative (ITBC), also known as the Intertribal Buffalo Council, is a non-profit organization, of 82 federally recognized tribes from 20 different U.S. states, whose mission is "to restore American buffalo to Indian Country in order to preserve the historical, cultural, traditional, and spiritual relationships for future Native American generations."

Surplus bison from places such as Badlands National Park in South Dakota, Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, and Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona are relocated to member tribes. Collectively, the ITBC manages over 20,000 bison on over 1,000,000 acres of tribal lands. Their web site states, "The ITBC was created to reestablish buffalo herds on Indian lands in a manner that promotes cultural enhancement, spiritual revitalization, ecological restoration, and economic development. ITBC is governed by a Board of Directors, which is comprised of one tribal representative from each member tribe. The role of the ITBC, as established by its membership, is to act as a facilitator in coordinating education and training programs, developing marketing strategies, coordinating the transfer of surplus buffalo from national parks to tribal lands, and providing technical assistance to its membership in developing sound management plans that will help each tribal herd become a successful and self-sufficient operation."

Nepal's new Constitution

The small Himalayan country of Nepal, after a decade of civil war that replaced a monarchy with a parliamentary democracy, included the cooperative sector in their new Constitution of Nepal of 2015, which states:

51(d3). Policies of the State: The State shall pursue the following policies:

to promote the cooperative sector and mobilize it in national development to the maximum extent...50 (3). The economic objective of the State shall be to achieve a sustainable economic development, while achieving rapid economic growth, by way of maximum mobilization of the available means and resources through participation and development of public, private and cooperatives, and to develop a socialism-oriented independent and prosperous economy while making the national economy independent, self-reliant and progressive in order to build an exploitation free society by abolishing economic inequality through equitable distribution of the gains...

© 2024 by John Curl. All rights reserved.

John Curl was a founding member of Heartwood Cooperative Woodshop in Berkeley in 1974, and worked there as a professional woodworker for over 40 years. He was a board member of the Network of Bay Area Worker Cooperatives in 2014-2015. In the 1970s-80s he was an organizer of the InterCollective (an earlier network of Bay Area coops), and an editor of the Directory of Collectives. He is the author of For All The People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America (PM Press, 2009, 2012), and The Cooperative Movement In Century 21 (PM Press, 2009). "It is indeed inspiring to be reminded by John Curl's new book For All The People of the noble history of cooperative work in the United States." Howard Zinn.

Header image by RoberManners CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Citations

John Curl (2024). Dystopia Nepal Express: Worker Cooperatives in a Workless Century. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/articles/dystopia-nepal-express

Comments

Leslie Simon

May 26, 2024, 4:37 am

Thanks for this well-researched and insightful article. Sobering but also inspiring.

martin hickel

May 27, 2024, 7:36 pm

echo leslie's comment -- another related topic might be the legislative efforts in this country to suppress the co-op movement through taxation & insurance regulations. (also "co-op" scans better than "coop" -- which is where chickens & rabbits live)...

Add new comment