Unit I, Unit II, Unit III, Unit IV, Unit V, Unit VI

[Translator's note: Just how different a solidarity enterprise is from a capitalist business becomes completely clear in this final chapter. Labor, Profit, Surplus, Capital, the C Factor: the terms and framework are not the same. Likewise, the final tasks, writing a business plan and bylaws (which Razeto has pushed to the end of the course) appear to be conventional but embody the principles and practical applications of solidarity, “the great force of efficiency that drives solidarity enterprises.”

In Unit I, the emphasis was on the C Factor and the need to build a solidarity group capable of creating a successful enterprise, “on firm ground and not shifting sands.” In the journey through Units II to V the solidarity group continued exploring the C Factor and strengthening the group, as they analyzed and defined their business idea and goals, the factors of production needed and in what proportions, where and how factors could be obtained, and finally the possible sources of external financing.

In Unit VI the group began to establish the economic organization of the enterprise: choosing and defining forms of property, admission of members, and governance and management. In the final Unit they complete that process, determining how they will remunerate labor, capital, and the C Factor and distribute surplus. The emphasis is on proportionality, which Razeto calls the second “great force for efficiency that makes the solidarity enterprise grow and develop.” The goal is to establish a system that is “just, efficient, and demonstrates solidarity.” Participants will appreciate the manual’s methodical approach when they write their bylaws and business plan grounded in a robust collective process and a deep understanding of the theory and practice of solidarity at work.

Any manual is limited; a manual that took into account every problem and possibility would be like Borges’ 1:1 scale map, as large as the terrain it charted.1 Still, it would be interesting to extend the analysis here to new examples of solidarity enterprise: platform cooperatives, Distributed Cooperative Organizations, multi-stakeholder cooperatives, and commoning.2

Moreover, this manual is designed to help a group create a solidarity enterprise, so it ends at the beginning of the journey. Many questions will arise, along with new problems and challenges. But founded in solidarity and collective thought and action, the group should be well prepared to find its path. – Matt Noyes]

UNIT VII

ECONOMIC ORGANIZATION OF THE ENTERPRISE (2)

Remuneration of labor and distribution of surplus

Session 13

Plan

- Gather, welcome, ice-breaker, form a circle, choose a moderator for the meeting.

- Evaluation of Unit VI.

- Each participant reads aloud their answers to the individual evaluation form from Unit VI.

- Carry out the group evaluation as described in the group evaluation form from Unit VI.

- Break, snack.

- “Reading Seven.” (One or two people read out loud as others follow along in the text.)

- Questions for review and discussion. (Participants volunteer to answer one question each, raising their hands to speak. Other participants can add to their answers but it is best if nobody speaks twice before others have had a chance to speak.)

- Questions for the facilitator, exchange of ideas and free conversation on the theme.

- Suggestions for the Individual Task. (The facilitator will explain the content and purpose of the individual task, clarifying any issues and answering questions that come up.)

READING SEVEN

Having considered what the group members bring to the enterprise, the factors of production they contribute, their effort, labor, varied understandings and creativity, we now arrive, finally, at the question of their compensation for the contributions they have made and the work they have done: how will the enterprise compensate its workers and members? The last two elements of the economic organization of an enterprise are the ones we mentioned in the previous reading: Remuneration of Labor and Distribution of Surplus. Our task now is to determine, theoretically, which criteria are best suited to a solidarity enterprise and later resolve the practical questions regarding the application of these criteria to the enterprise, adapting them to the concrete conditions of the Solidarity Group.

The Remuneration of Labor

This is a decisive question for a solidarity enterprise because labor is the principal factor that its creators and members invest.

Now, when we analyzed the factors of production we saw that in solidarity enterprises the labor factor should be treated as an internal, not external, factor, to be remunerated not through a contractual set salary or wage but through the distribution of surplus or profits generated by the enterprise. Based on this criterion, remuneration of labor is not established as a fixed amount, but as a percentage of the surplus generated. If the enterprise earns more revenue, the payment to labor is greater, and if it revenue declines, workers have to make do with what they have managed to produce.

We said that the problem this system presents – the fact that workers need income on a regular and more frequent, typically monthly, basis (distribution of surplus is often done at the end of the year) – can be resolved by establishing monthly payments to workers known as anticipated distributions of the surplus reflected in the annual financial statement.

But the principal problem when it comes to remuneration of labor is not the way it is conceptualized (in reality, if set salaries were established they would have to be deducted from the earnings and the end result would be the same, the only difference being a greater uncertainty for the enterprise and more difficult accounting). The most important thing is to establish how much of the total surplus to distribute, based on the work each worker has done for the enterprise.

There are three possible criteria:

Option 1: “everyone is paid the same.”

Option 2: “to each according to their needs.”

Option 3: “to each according to their work.”

Which is most just? Which expresses the deepest solidarity? Which is most efficient? Let us see.

Option 1

In this case all members receive the same payment for their work, even if some work more than others, and even if members have different needs. “All members are equal” seems to be a criterion of justice and solidarity, but in fact it is not. How can it be just that all receive the same amount with no consideration of the needs of each individual or the work that they contribute? Should a dedicated worker with a large family to support get the same amount as a lazy worker who lives alone? Is that solidarity? A system in which all workers receive the same pay would only make sense if all workers did the exact same work, or, if not, if they rotated positions frequently; but it is easy to see that in this case the actual principle at work would be “to each according to their labor,” resulting in equal pay for all.

Option 2

In this case, payment varies with the greater or lesser needs of each worker and not the amount of effort each makes. “To each according to their needs” seems clearly to reflect a spirit of solidarity, but in reality it is unjust and, if we examine it closely, lacking in solidarity as well. Moreover, it is inefficient because it removes a stimulus for doing work of high quality and efficiency. On the contrary, this criterion stimulates the expansion of needs regardless of what the worker does to meet them. Nonetheless, this criterion can be applied in some cases in which the group bond is so strong that each member feels the needs of the other as their own, and the well-being of the group depends directly on the satisfaction of each member’s needs. In a family, for example, or an intentional community in which many goods and services are shared and many needs are met in common. It may also be suited to situations where the principle objectives of the solidarity group are social, cultural, or of shared utility, and the generation of profits to be distributed among the worker members is of little importance.

Option 3

To each according to their work signifies that payments are based on the quality and time of the labor each member performs, in other words, productivity: payment depends directly on the contribution made by each worker to the generation of surplus. This criterion is efficient, since it stimulates each worker to make a greater effort. It is also fair, in that each is paid based on their contribution. But does it meet the criterion of solidarity?

This is an interesting point because it raises another very important question: what is the relation between justice and solidarity? A full treatment of this would require a long exposition. We will limit ourselves to making three assertions, which we offer up for the group’s reflection.

First assertion: something can be just but not have the character of solidarity.

Second assertion: that which is unjust can not make for true solidarity.

Third assertion: it is the role of solidarity to correct injustice and make justice more perfect.

If we apply these three assertions, the first step would be to establish a system of payment that is just. In a spirit of solidarity, we can not accept that which is unjust, and have to correct any injustice. So, the first principle is “to each according to their labor” recognizing the productivity of each person, their effort and skill, and the contributions they make to the generation of profits for the enterprise.

But while this is a necessary condition for a solidarity enterprise, it is not sufficient. Though it might be just, does it amount to solidarity in remuneration of labor? It could lead, for example, to excessive differences between members, based on opportunities for professional training that some had but not others, or a situation in which privileges matter more than the will and effort of each person. The members need, then, to find a way to use solidarity to correct that which remains unjust and perfect that which is just, without negating the principle of paying each worker according to their performance and productivity.

Can the enterprise provide training opportunities to less qualified workers, in order for them to gain skills and thus raise their productivity and earnings? This would be an application of solidarity to the problem of unjust socio-economic differences.

Can the enterprise establish a solidarity fund, with proportional contributions from all members, with which to meet certain needs for which the income some workers earn is insufficient? This would be a case of perfecting a just payment system by infusing it with solidarity.

Each group has to think about how to resolve this equation, establishing a form of labor payment that is just, efficient, and demonstrates solidarity. We will come back to this theme; and later, in the exercises for this Unit, we will see how to apply these general criteria in practice.

But first we need to consider a more general question that arises from what we have said so far: if labor payments should be considered distributions of surplus, what is this surplus? How much of it should be used to remunerate labor? How much should go to other factors or to reinvestment in the enterprise for growth or improvement?

What is surplus and how is it calculated in a solidarity enterprise? Is it the same as profits?

We need to make a conceptual distinction between “surplus” and “profits.” Until now we have used the terms interchangeably but at this point we need to specify, based on our understanding of the nature of solidarity enterprises.

In solidarity enterprises, the concept of surplus is used to describe the result of the total revenues in a given period (usually a year), minus the total costs paid to third parties (outside the enterprise), such as fixed costs, rents, financing costs, raw materials, salaries for workers who are not members of the enterprise, payment of debts, taxes, etc. Surplus refers to the value left over, which belongs to the enterprise and its members and can be used to compensate the internal factors of production and for growth of the enterprise’s equity.

To calculate the surplus one simply subtracts from the total annual revenues all costs paid for external factors and any expenses that represent transfer of money to entities outside the enterprise. Thus surplus includes payments for labor done by members, whether paid as anticipated distributions or in fact paid at the end of the year. It also includes the money dedicated to reinvestment in the enterprise such as purchase of machinery, technological improvements, amortization of debt, inventory of supplies and products, etc., anything that implies an increase in equity for the enterprise. This also includes the payments to members as recompense for their contributions of capital or other factors.

In practice, in a solidarity enterprise, surplus is not so different from profits but we will use the term profit only for current accounts as normally calculated, which is also the basis on which taxes are calculated. The main difference between profits and surplus, understood this way, is that to calculate profits one must also subtract labor payments and distributions to members. This concept of profit is useful for comparing the efficiency of a solidarity enterprise to that of capitalist enterprises which, obviously, do not include labor costs as part of profit.

Having defined surplus and profit in this way, the question is how to distribute surplus among the members of a solidarity enterprise.

Distribution of Surplus

This is the final and most complex aspect of the economic organization of an enterprise. We need to apply here the criteria of justice, solidarity, and efficiency and adapt them to the characteristics of the enterprise we are creating.

We have already taken a big step, defining the key criterion for payment of labor as “to each according to their work.” This criterion gives us the general pattern for distribution of surplus which is distribution to each in proportion to their contributions to the enterprise.

All factors contributed by members should be remunerated, not just labor, but financial contributions, materials, technology, management, and also the C Factor. Surplus should be used to recompense all factors and each member will receive a percentage of the surplus corresponding to the percentage of the factors they have each contributed to the enterprise.

The issue is determining the proportions in which each factor will be remunerated and then to see how much surplus goes to each member, according to the contributions they have made. Although it is not easy to understand and apply, it is fundamental that we understand this approach clearly and apply it rigorously: what is at stake is as much the special logic of the solidarity economy (the character of the solidarity enterprise) as the efficiency of operations, which depend on these criteria.

Remember, first of all, that each enterprise has its “theorem of defined proportions,” a particular combination of the six productive factors. This is important because the surplus generated by the enterprise should be distributed to each factor according to the specific proportions in each enterprise, according to its “theorem.”

We have already defined the “theorem” of our enterprise, not just in general or theoretical terms, but concretely: we know the quantity of each of the six factors to be employed. To determine the proportion of the surplus to be used to compensate each factor we need to know their productivity. This theme raises tricky theoretical questions that we will not address here, instead we will approach the question simply and pragmatically based on signals and indicators that we receive from the market. In effect, the market assigns prices to each factor based on its average productivity, the contribution that factor can be expected to make to enterprises. While such prices can be distorted, in practice they are the prices at which members of the solidarity enterprise can obtain or sell factors to other enterprises.

So, to determine the proportion of surplus going to each factor, we sum the market prices of each factor, then divide the price of each factor by that sum, giving the proportion in which each factor should be remunerated in the distribution of surplus.

But as the market does not operate according to the logic of solidarity economy, we need to make two adjustments:

1) We need to adapt to the market by simplifying the information about the value of factors, reducing them to two basic factors for which the market sets clear prices: labor power and capital.

2) At the same time we need to correct the market, adding a special remuneration for the C Factor, which the market ignores and does not value, but we know to be essential to the success of a solidarity enterprise.3

So we have to resolve three things:

1) How much of the surplus should go to compensate labor?

2) How much of the surplus should go to compensate capital?

3) How much of the surplus should go to compensate the C Factor?

The Remuneration of Labor According To Professional Qualifications And Management Roles

We begin by returning to the remuneration of labor, which we have partially addressed, adding a question: is the labor of an engineer more productive than that of an unskilled worker and should it be better paid? If so, why? Why is the labor of a department head considered more productive and better paid than that of a worker in the same department? In general, why are the contributions of workers with professional training considered more productive than those made by less skilled workers?

These questions may seem obvious but they point to a reality with which is familiar but should be questioned.

The labor power that an engineer or department head (more generally a professional and highly skilled worker) brings to the enterprise incorporates important elements of other factors, mixed together in the same person: in this case elements of technology and management. Said differently, three factors are present in the contribution that each person makes to the enterprise: labor power, technology, and management, and they are exercised simultaneously. The productivity of a member, or their contribution to the enterprise, is determined not just by their labor power but by the technology and management their work includes as well. So the different rates of pay or salary that workers typically receive in an enterprise, based on their skill levels and the degrees of management responsibility they take on, reflect in fact their contributions of three combined factors.

Based on the information we get from the market regarding the remuneration of labor power (which in fact includes elements of technology and management), we can determine jointly the proportions of surplus that go to each member based on their contributions of labor, technology, and management. Jobs with a higher technological content, or positions with greater management responsibility, will be recognized for their greater contribution to the enterprise and obtain a higher percentage of the surplus. We will do the specific calculations in the Exercises and the Jornada for this Unit. For now, on the level of theory, the key is to understand that we will determine the contributions of these three factors jointly based on the information provided by the market as to the normal levels of remuneration assigned to people based on skills, training, and the roles and responsibilities they assume.

The Remuneration of Capital According to the Amount Contributed by Each Member

As for the remuneration of capital, we use the same criterion: the information provided by the market. But we need to understand clearly what we are doing and why; it is crucial that we be convinced and sure that what we are doing is just and done in a spirit of solidarity and is not used as a cover for any form of capitalist exploitation.

First of all, we need to be clear about what capital it is that we are talking about. We are not referring to external financing that we obtained through borrowing. The payment of that debt is a cost for our enterprise and has to be paid as agreed with the agreed rate of interest and timeline. When paying these costs we are not distributing surplus but bearing the costs of borrowing, even if the loans were made by friends, family members, or even a member of the enterprise.

When we talk about remuneration of capital we are talking about the enterprise’s own capital, members’ financial contributions and the monetary value of the materials of production and other factors they contributed, individually or as a group, that are now property of the enterprise. We calculated the monetary value of the factor contributions made by each member so we know the total amount of this capital as well as the amount contributed by each member. What we need to specify now is what portion of the surplus generated by the enterprise will go to remunerate these capital contributions.

You may have heard of the old principle of cooperativism “limited interest on capital.”4 This principle signifies the intention to pay capital as little as possible. We reject this principle. We will forget it, ignore it, and not apply it, for two reasons: 1) because it is unjust, and 2) because it is inefficient.

The idea of paying capital as little as possible comes from the notion of capital as an external, hostile, force which threatens to subordinate and oppress us.5 This is true of capitalist firms but not solidarity enterprises. In a solidarity enterprise the members of the solidarity group themselves contribute capital which remains under their collective control. Their capital is the result of the effort and sacrifice made by members of the solidarity group on behalf of their enterprise. When a member contributes capital to the enterprise they are sacrificing other needs that could be satisfied with those resources or that money. They are contributing savings accumulated from their previous labor, not alienated labor they accumulated by exploiting others. The contributions of capital made by members deserve fair compensation. Above all they need to be properly valued: not only are they contributing their own accumulated labor and sacrificing other consumption and satisfaction of needs, but they are doing this for the benefit of the solidarity enterprise for which they are taking a risk. In effect, if the enterprise fails to generate the expected surplus, or is inefficient, the members risk losing everything they worked so hard to have. For this reason, it is right to provide fair compensation for these contributions of capital.

Moreover, if we do not compensate this capital fairly it will be more difficult to obtain. Our enterprise will never have much capital, our labor will not bear the expected fruit, and the operation will be inefficient. It is just to provide members fair compensation for the capital that they contribute. It is evidence of solidarity and it is efficient. The question is: how much of the surplus should go to compensate members for their capital contributions?

Again we can use the criteria of the market: what is the cost of capital in the market?

In the market, capital has two prices, the acquisition price and the borrowing price. The acquisition price is the interest rate that banks pay depositors. The borrowing price is the interest rate that banks charge borrowers. Which price should we consider when calculating the value of the capital contributed to the enterprise by members? The answer depends on how we look at it, from the standpoint of the member or from the standpoint of the enterprise. In one case, the member benefits at the expense of the enterprise, in the other, the opposite occurs. The simplest solution, and the fairest, is to take the average of the two prices. If the rate of acquisition (interest paid by a bank for deposits), is 1% and the lending rate (interest charged on loans, is 2%), a fair rate would be 1.5%. This is good for the member since they are earning more than they would have had they deposited the money and for the enterprise since they are paying less for capital than they would if they borrowed the money from a bank.

But watch out! We are not assigning fixed values, payments of predetermined sums, any more than when we set the payment for labor by the standard salaries set by the market. In both cases, the criteria we take from the market are only used to establish proportions of the surplus to be distributed to labor and capital.

We will learn how to calculate these proportions in practice in the Exercises and the Jornada for this Unit. For the moment what matters is just to understand the problem theoretically. And it is fairly simple:

1. You add up the values of the monthly payments that members would be paid in the market for the jobs that they do in the enterprise, resulting in a monthly total payment to labor.

2. You add up the value of all the valorized equity contributions made by the members, which constitute the capital belonging to the enterprise, and apply to that amount the monthly interest rate obtained by averaging the acquisition price and the borrowing price, which gives you a monthly payment for capital.

3. You add the two monthly payment amounts and calculate the percentages of the total for each amount which correspond to the proportions of the surplus that go to labor and capital, respectively. (Remember that both the labor and the capital we are discussing here are contributed by members.)

4. You then calculate the percentage of surplus distribution that goes to each member, according to their particular contributions of labor and capital.

What about remuneration of the C Factor?

We already know that in addition to the factors that we gathered under the main categories Capital and Labor, in a solidarity enterprise a third main factor is at work, making a relevant and indispensable contribution to production: the C Factor. In capitalist enterprises, too, the C Factor is present and contributes to production, but it goes unrecognized not to mention uncompensated.

In the solidarity economy, on the other hand, we recognize the C Factor as an essential factor that needs to be stimulated, kept alive, cultivated, and always maintained for its contribution of solidarity. It is often said that over time solidarity enterprises lose their initial mystique, the power of unity and solidarity that they had at the start. I believe this is closely related to the lack of recognition and compensation of the C Factor and failure to constantly stimulate its development. This is why we call attention to the C Factor, so often forgotten, even in the solidarity economy. We also include it in the calculation of the distribution of surplus in our solidarity enterprise.

So, if the C Factor is entitled to a portion of the surplus to be distributed, how much should it receive?

Here the market is of no help, because this factor is not valued or paid for on the market. We have no choice but to determine its price in our group, using our own criteria. The proportion of the surplus that we assign to the C Factor will vary with our appreciation of its importance in our enterprise relative to capital and labor. If the investment in capital and labor is very slight, we will assign a greater proportion of the surplus to the C Factor. If, on the contrary, the enterprise operates with a lot of capital and many workers, it may be appropriate to reduce the percentage of the surplus going to the C Factor.

The most important consideration is the quality of the C Factor. When we introduced it in Unit One, we noted that various studies of capitalist enterprises had shown that productivity could be raised up to 30% by improving internal relations, and that in solidarity enterprises it could be raised even higher, the C Factor being the principal factor determining the success or failure of an enterprise. As there can be wide variations in the strength of internal cohesion in a group, resulting in greater or lesser productivity of the C Factor, we urge each group to assign a percentage that takes into account as much the quantity of capital invested and the number of workers in the enterprise as the degree of unity of will and commitment to shared objectives. In any case, as a suggestion, and basing ourselves on the old cooperative practice of reserving 20% of the surplus for cooperative education and the cultivation of participation, we believe it is reasonable to assign to the C Factor between 20% and 30% of the surplus generated by the enterprise (no less than 10% and no more than 40%). Less than 10% and you run the risk of weakening the logic of solidarity, over 40% risks harming the efficiency of the enterprise in the market, by undervaluing the productivity of labor and invested capital.

Obviously, having determined the percentage of surplus to dedicate to the C Factor, the remaining surplus should be divided between the other factors, in proportions we have already shown how to determine. In other words, 100% of the surplus goes to these three factors: Capital, Labor, the C Factor.

Naturally, the portion of surplus going to the C Factor is not distributed directly to individual members but to the solidarity group, the collective of worker-members. It can be used to develop group activities, recreation, education, communication, etc., anything that helps increase and improve the group’s sense of solidarity. Part of the money can be used for solidarity by covering needs in case of health emergencies or other crises that can affect members, or to reward and encourage certain behaviors and qualities in members (a prize for the best member, bonuses for commitment to the enterprise, etc.). Finally, the money could also be reinvested in the enterprise, increasing the portion of equity owned by the group, assigning the group corresponding shares in the enterprise.

Having defined in this way the percentages to be distributed among the members and to the solidarity group as a collective, for their contributions of labor, capital, and the C Factor, we need to address a final question concerning the assignment and use of surplus:

How is the distribution carried out, given that it may be in the interests of the enterprise and the group to re-invest some of the surplus in the enterprise?

The question arises because we calculated the surplus by taking the total annual revenues and deducting only payments made or owing to third parties for external factors, based on the concept of surplus we have defined as proper to solidarity organizations. Thus, the surplus includes payments to members for their labor, whether paid monthly as anticipated distributions or distributed at the end of the year. It also includes money which is to be reinvested in the enterprise, for example by purchasing new machinery, technological improvements, amortization of debt, inventories of supplies or finished products, etc., which imply some increase in the equity of the enterprise or the factors in its possession. The question, then, is how to assign to individual members and to the collective that part of the surplus to which they are entitled but can’t be distributed in money form since it has already been reinvested in the enterprise or will soon be?

We need to be clear that, in the first place, the decision about how much to distribute to members in money, how much to invest in the enterprise, and how much to spend on activities that benefit the group, has to be made by the Member Assembly. This decision is made, definitively, when the Assembly approves the balance sheet and the income statement for the year and the budget for the next year. The only criterion here is what makes sense for the enterprise, the interests of the members, the needs they face from the market. Nonetheless, as a kind of guideline for evaluating the health and equilibrium of the enterprise and the decisions to be made, it may be helpful to think in terms of a certain balance between the product of each factor and that which the factor is due, based on its remuneration, i.e.:

- The money which is distributed to members should not differ too much from the amount that is assigned to remunerate the labor factor.

- The money invested in the enterprise should not differ too much from the amount assigned as remuneration to capital.

- The money spent for the benefit of the group and on solidarity activities, internal and external, should not be too different from the amount dedicated to remuneration of the C Factor.

As to the mode of distribution, based on the criteria we have examined, it is clear that all the money reinvested in the enterprise, and thus implying an increase in the equity, should be reflected in the ownership structure. Members will see their shares rise or fall at the end of each year according to the amount that they are due to receive (in accordance with the factor contributions they have made). Concretely this is expressed in the issuance of shares and their assignment to individual members. We will see how this is done in the Exercises and the Jornada of this last Unit of the Manual.

So we reach the end of the manual which has led us to the understanding that in solidarity enterprises every contribution and every remuneration is proportional. Economic justice is found in this proportionality, as is the great efficiency of this type of enterprise. It is due to this principle of proportionality that solidarity enterprises are so resilient in times of crisis, automatically adjusting when surplus falls and never taking on losses that lead to bankruptcy.

We have also understood that it is due to the application of this same criterion of proportionality that solidarity enterprises stimulate to the maximum the factor contributions of members and increase their productivity. Remuneration is proportional to contributions: every new contribution, every effort, every innovation is soon recompensed, and there is no fear that one’s contributions and the good they do to the members and the solidarity group will go unrecognized or that someone else will unjustly appropriate that which one has contributed.

In this way we conclude the theoretical part of this manual much as we started it. We began by showing how the principal of solidarity which takes material form in the C Factor is the great force of efficiency that drives solidarity enterprises. And we end by showing how the principal of justice translated into criteria of proportionality is the other great force for efficiency that makes the solidarity enterprise grow and develop. Solidarity, efficiency, and justice are the three pillars of solidarity economy, upon which successful solidarity enterprises are built.

So we have completed our study of the concepts and theoretical criteria that need to be kept in mind and applied to the creation, organization, and operation of a solidarity enterprise. If if we understood it well, and if we carefully apply what we know, we can rest assured that we are constructing our enterprise on firm ground and not shifting sands.

Questions for Review and Discussion #7

The following questions should be answered individually, in writing. Each participant will later share their answers during the group work, allowing for evaluation and correction of the answers by comparing them with the answers of other members followed by discussion.

- Why, in solidarity enterprises, are members paid a proportion of surplus for their labor instead of fixed salary?

- How should the enterprise resolve the problem that members need to be paid regularly, at least monthly, but the surplus is only calculated at the end of the year?

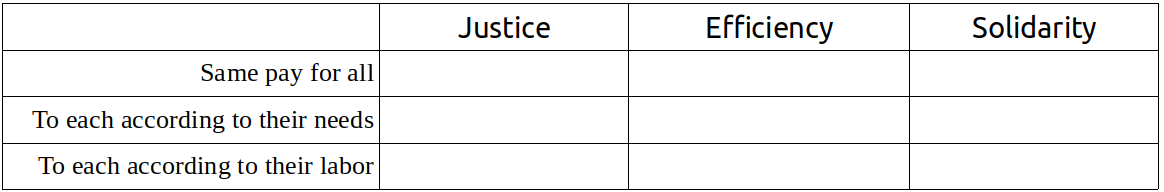

Check the box for each criterion that applies to the three remuneration systems that can be used in a solidarity enterprise:

- Why do we say that something unjust can not have the character of solidarity? How does solidarity correct injustice and improve justice?

- What is surplus in a solidarity enterprise? How is it calculated? Is surplus the same as profit?

- What is the main criterion that defines the general pattern of distribution of surplus in a solidarity enterprise?

- Why, in a solidarity enterprise, should capital be remunerated according to the same principle as applied to labor? Why is providing adequate compensation for capital an expression of justice and solidarity?

- How do you we explain the fact that the labor of an engineer is more productive and better paid than that of an unskilled laborer? Why is the labor of a department head more productive and better paid than a regular employee in the same department?

- Why do we use market prices of capital and labor as a reference when determining the proportions in which each factor should be remunerated in a solidarity enterprise?

- Why do solidarity enterprises also remunerate the C Factor? How do you determine the proportion of surplus that should go to remunerate the C Factor? Who receives the share of surplus assigned to the C Factor?

- How, in what form, do members receive their share of the value of the surplus that is reinvested in the enterprise?

- Who decides, and at what moment, how much of the surplus is distributed in money form to members, how much is reinvested, and how much is spent by the group?

- What criterion can we use to evaluate if we are wisely balancing our distributions of surplus between these three uses? (see prior question)

INDIVIDUAL TASK #13

To be done after the thirteenth session

- Study the Glossary at the end of Unit VII.

- Answer the “Questions for Review and Discussion #7” in writing in your notebook.

- Individual or Small Group Activity: Exploring Pay Structures in the Labor Market.

Individual or Small Group Activity:

Exploring Pay Structures in the Labor Market

In this activity, group members collect information about salaries and other remuneration for labor in enterprises of a similar size and type to their own, including differences in pay based on professional level, skill, and roles and responsibilities. This information will be used as a reference for determining the percentages of surplus to be distributed to members of the solidarity enterprise based on their different jobs and positions of responsibility. Members of the group should obtain as much information as possible, according to the type of enterprise and its area of activity. To the degree possible they should obtain complete pay schedules from businesses to the one they want to create, or businesses that are different but can still serve as a reference for the solidarity enterprise. It should be remembered that proportions are more important than amounts, so it is important to collect complete data about the whole pay structure in a given enterprise and not just data about particular jobs.

Each person or small group will organize the information collected in their notebooks such that it will be easy to share and analyze with the group.

Session 14

Plan

- Gather, welcome, thematic game, form a circle, choose a moderator for the meeting.

- Reading and commentary on the answers to Questions for Review and Discussion #7. (If the group is large, each participant will read only one or two responses.)

- Exercise #13. Determining the Pay Schedule.

- Break, snack.

- Exercise #14. Calculating Percentages of Surplus to be Distributed to Members for their Labor.

- Assignment of Individual Task.

- Reading and Organization of Jornada #7: “Organizing the Enterprise (II)”

Exercise #13

Determining the Pay Scale

Explanation

The worker-members of the enterprise carry out different jobs, each requiring specific skills and varying degrees of management and leadership responsibility. Because each job makes a different contribution to the enterprise they deserve different levels of remuneration. So it is necessary to determine the percentages of the surplus to be distributed to the different members as workers (that is, according to the work they do in the solidarity enterprise). Following the criteria we described above, they should take as a reference the rates of pay (salaries and wages) that apply to similar jobs in the market. We need, then, to create a pay scale for the various jobs that will be done in our enterprise. In this exercise, we will stick to establishing a pay scale for the different jobs and positions, assuming that each is done full time, without yet considering who will do the job nor how much time will be dedicated to each one.

The Flow

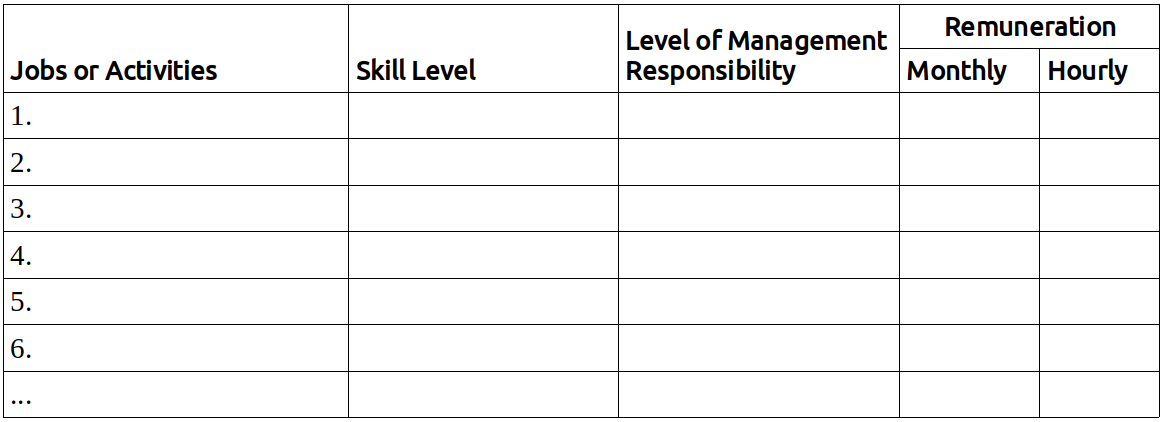

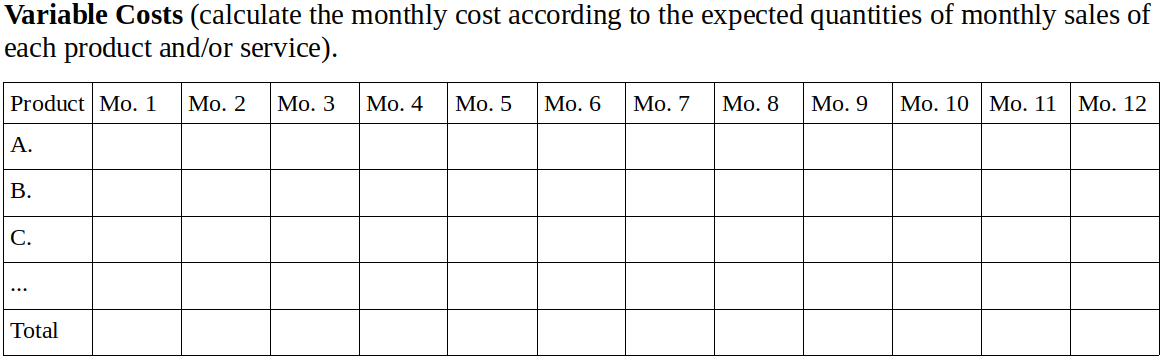

1. Prepare the white board or flip charts with this table:

2. In the column, “Jobs and Activities” write the different jobs and/or labor activities that need to be done in the enterprise and will be done by members.

3. In the column, “Skill Level” there are three levels:

a) Unskilled (not requiring special study or training)

b) Technical (requiring technical study or specialized experience)

c) Professional (requiring university study or higher education)

4. In the column “Level of Management Responsibility” there are also three levels:

a) No management responsibility

b) Medium responsibility

c) High responsibility

5. In the column “Monthly Remuneration” note the salary or wage paid for each type of work or activity in businesses of similar size and type, as well as the levels of skill and responsibility. Base these figures on the research done in the previous Individual or Small Group Activity.

6. In the column “Hourly Remuneration” note the hourly pay rate, which can be obtained by dividing the monthly figure by 200 (the approximate number of hours worked in a month).

Exercise #14

Calculating the Percentage of Surplus to be Distributed to Members for their Labor

Explanation

In this exercise the remuneration to be received by each worker-member will be established, based on the prevailing pay rates in businesses of similar size and type. Later, based on these figures, we will calculate the percentages (%) of surplus to be distributed to each member in accordance with their contributions of labor. As each worker-member may do more than one job, or may hold more than one position of management or leadership responsibility, the numbers of hours (per week) dedicated to each job or position need to be estimated. Later we will convert them into percentages of a full work day (based on a 48 hour work week). It is clear that later, in the exercise in which we calculate the percentage of remuneration for each worker-member, we will discount days and hours not worked.

The Flow

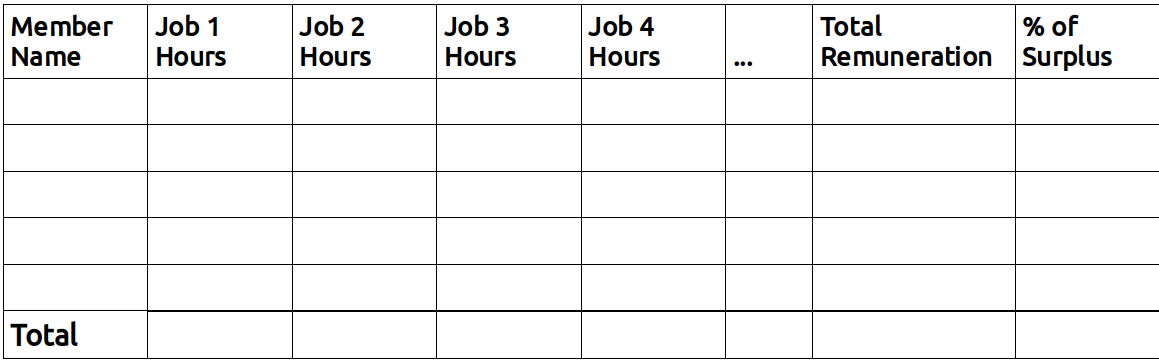

1. As in the previous exercise, a canvas is drawn on the white board or a flip chart:

2. Write the names of the worker-members and note the hours worked by each person in the various jobs defined in the previous exercise.

3. Multiplying the hourly value for each job by the number of hours worked, determine the amount of money that would be paid to each worker based on the standard market value.

4. Based on the total value of remuneration owed each worker, calculate the percentages of distribution of surplus to which each member is entitled, given their labor contributions.

Individual Activity #14

Research on Interest Rates Charged in the Financial Market

(to be done after completing Unit 12)

Do this as preparation for Jornada #7, as indicated in the instructions.

In this activity members visit banks to inquire about the interest paid on deposits and the loans, pretending to be potential customers. The amount to be borrowed or deposited is the total value of the capital owned by the enterprise, as calculated in Jornada #6. The members should organize themselves, dividing up the various banks to be visited, such that different members will visit each bank, one pretending to be a potential borrower, another a potential depositor. The information can usually be obtained by reading leaflets or displays in the bank, or on the bank website, but it is important that the members do this in person, especially those members who have never sought business loans, learning in this way not just the interest rates but the conditions required of borrowers. On top of the experience to be gained, it may turn out to be useful for future negotiations they do on behalf of the enterprise, enabling them to obtain more precise information, since the interest rates can be personally negotiated depending on the amount of money involved.

Jornada #7

Organizing the Enterprise (II)

What is this practical activity about?

This is the final Jornada to be done as part of this course on creating solidarity enterprises. There are three tasks:

a) Organize the system of distribution of surplus.

b) Do an individual and group evaluation of the seventh Unit.

c) Understand the Final Projects of the course and prepare to carry them out.

How to prepare and organize the Jornada

Just as in previous Jornadas the preparation and organization is done in the previous Session (#13), where the explanation is read, individual tasks are assigned, and the day of group work is organized following the instructions given below.

As the group has done several Jornadas already and is capable of proceeding efficiently, it is not necessary to go into too much detail. As in Jornada #6, the solidarity group will make binding decisions of great important for each worker-member of the enterprise that you are creating. For this reason it is crucial that all the members who are involved in the creation of the enterprise be present and contribute to the decision-making process. As in the previous Jornada, members who choose not to become members of the enterprise can still participate in the Jornada but should not participate in any decision-making by the people who will be the founding members of the cooperative or association.

What should members bring to the Jornada?

- Each person or small group should bring the information gathered in the Individual Activity on Researching Interest Rates for Borrowing/Saving.

- A pocket calculator (or phone app) for calculating percentages and other simple operations.

- All the materials from Exercises #11 and #12.

- All the materials and information from Jornada #6 “Organizing the Enterprise (I)”, and Exercises #13 (“Determining the Pay Scale”) and #14 (“Calculating the Percentage of Surplus to be Distributed to Members for their Labor”).

- The group symbol, logo design, and business idea.

- A flipchart.

- A large blackboard or other board.

- Plenty of index cards (10cm x 20cm) in six colors.

- Updated account information (personal and group).

- Handouts for each member:

- Individual and group evaluation forms for Unit VII

- Handouts for the final projects: “Creating Bylaws and Rules for the Solidarity Enterprise” and “Creating a Business Plan for the Solidarity Enterprise”

- All the information collected during the course, in the Exercises, Activities and Jornadas.

How should the jornada be carried out, what is the plan for the day of group work?

This jornada is essentially a work session that can be done in about four hours, though the group may decide to add other activities that they think would be good to include.

The jornada follows this plan:

- Gathering, welcome, thematic game. Installation of the group symbol in an appropriate place. Selection of a moderator for the meeting, as well as a “canvas manager” (person who manages the bulletin board or display used in the activities), and a note-taker.

- Set up the materials from Exercises #13 and #14, as well as Jornada #6.

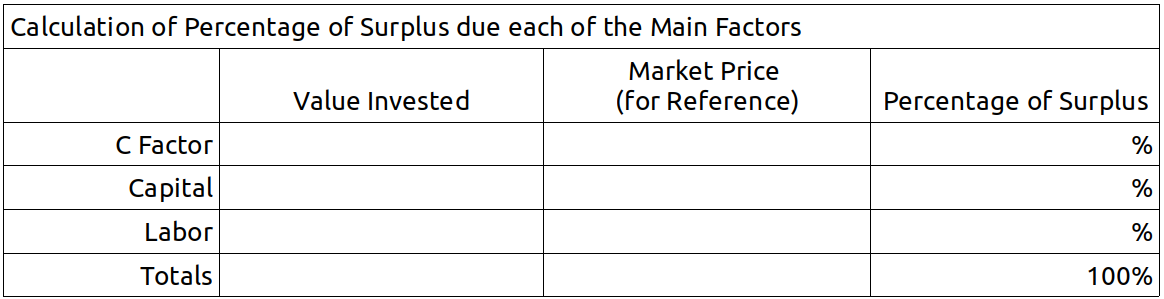

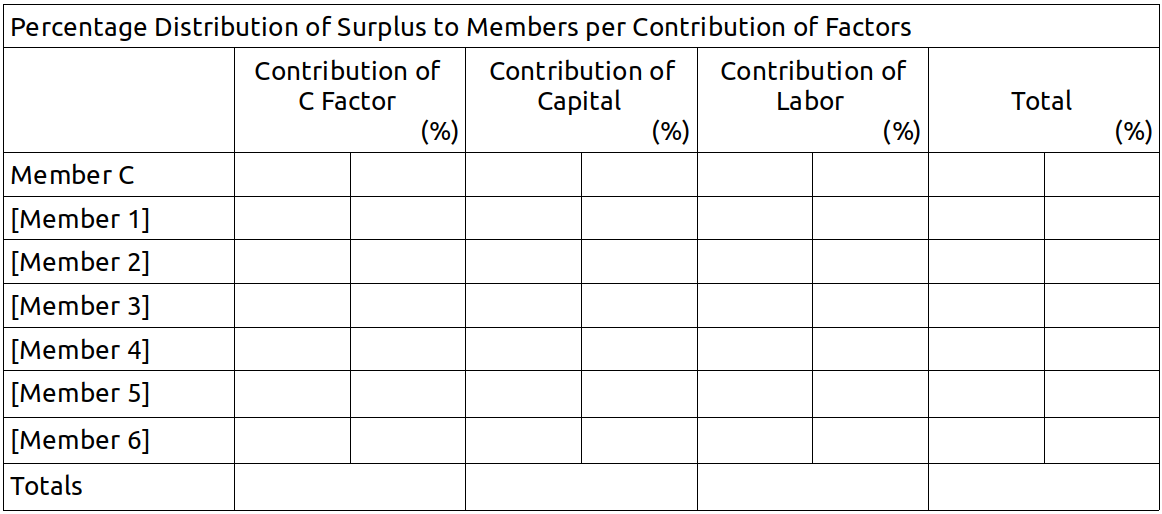

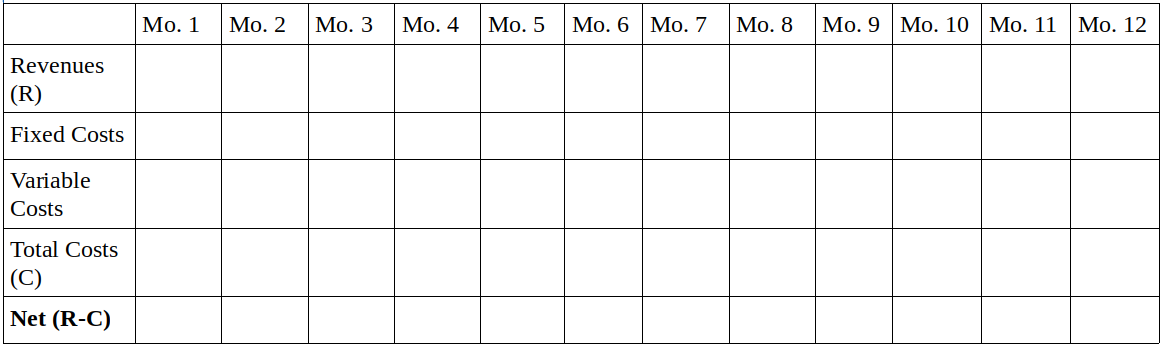

Preparation of the canvas for calculating the percentages of surplus going to the C Factor, Capital, and Labor, using this layout:

Preparation of the canvas for calculating the percentages of surplus going to each worker-member, using this layout:

- Activity 1. Determining the percentage of surplus that corresponds to each factor.

- Activity 2. Determining the percentage of surplus that should go to the members.

- Break and Snacks

- Activity 3. Preparation for Final Project #1: Writing the Bylaws and Rules of the Enterprise.

- Activity 4. Preparation for Final Project #2: Creating a Business Plan for the Enterprise.

- Evaluation of Unit VII

Contents of Activity 1

The calculation of the percentages of the surplus what will be distributed in accordance with the contributions of each of the main factors (Labor, Capital, C Factor) is based on information already in the group’s possession. This information will be gathered and processed in the canvas prepared as described above (Calculation of Percentage of Surplus due each of the Main Factors).

We proceed by the following steps:

First, fix the percentage of the surplus that should stay with the solidarity group as such, as remuneration for the C Factor. In the reading we already noted that this percentage needs to be established by the group itself between a minimum value of 10% and a maximum of 40%. Between these extremes, the percentage can rise if the cohesion and unity of the group is especially high and strong and the investments of capital and labor are not very high. If, on the contrary, those investments are large and the group does not have many aspects of shared life, the percentage going to the C Factor can approach the lower limit. Once the percentage has been decided, note it in the first line of the fourth column.

a) Continue by noting in the second line of the second column the value of the capital invested.

b) Calculate the percentage of surplus to be dedicated to capital, based on the average of the rates of interests offered/charged by the banks for one year, based on the information gathered in the Individual Activity, and, summing and dividing, find the average annual interest rate.

c) Apply the average annual interest rate to the total amount of capital invested and note the result in column two, line two.

d) Calculate the total annual amount of labor remuneration, multiplying by twelve the monthly amount of remuneration to worker-members calculated in Exercise #14.

e) With this data you can now calculate the corresponding percentages of capital and labor, which, added to the C Factor, amount to 100% of the surplus. Note the percentages in the second and third lines of the third column.

Contents of Activity 2

The calculation of percentages of surplus that will go to individual members should be a simple mathematical calculation, since you have all the information you need. But it is best to do the calculation together, as a group (or by one member in the presence of the group), so that all the members can clearly see how the percentages were determined and understand the theoretical basis on which the profits of the enterprise are to be distributed to members. (We say “theoretically” because in reality the contributions that each member makes can vary: the actual contributions of factors may be different from what they pledged. In particular, remuneration for labor is calculated on the assumption of no loss of labor time, for example due to absences from work. Obviously, at the moment of calculating each person’s share of the surplus absences and other gaps in factor contributions will be discounted proportionally.)

The calculation of percentages of surplus going to each member is done on the canvas, following these steps:

a) The percentage going to the C Factor is noted on the first line of column one (assigned to Member C, or the group itself) and in the total (last row of column one).

b) The totals corresponding to the capital and labor factors are noted on the last line of columns two and three and should add up to 100%.

c) Note in the corresponding cells the data for the labor and capital contributions of each member, using the data collecting in previous Exercises and Jornadas.

d) Calculate the corresponding percentages and verify the result, summing each column and the final total of member contributions, both of which should total 100%.

In this way the group has completed the calculations with regards to the main aspects of organization of the enterprise and each members knows the exact value of the contributions they will make and the corresponding remuneration they might obtain from the surplus generated by the enterprise.

Thus concludes the process of economic organization of the solidarity enterprise. Members can now proceed to the writing of the Bylaws, the norms that institutionalize and guarantee the operation of the enterprise. As we will see, elaborating the Bylaws consists of giving the enterprise a legal form corresponding to its economic organization. In other words, the “criteria” used to resolve the five aspects of economic organization are converted into “norms” in the Bylaws that define its juridical organization.

Contents of Activity 3

All that remain to be done are the two final projects: writing the Bylaws and creating the Business Plan. These final projects require the group to continue meeting until they are finished, at which point the enterprise can be launched.

The two final projects should be planned and prepared during this Jornada, following these three steps:

a) Read the material in the manual about how to write the Bylaws.

b) Discuss and assign tasks.

c) Set the date and place of the meeting where the Bylaws will be completed and adopted.

Contents of Activity 4

Having prepared and planned the writing of the Bylaws, the group should prepare the Business Plan for the enterprise, following the same steps:

a) Read the material in the manual about how to create the Business Plan.

b) Discuss and assign tasks.

c) Set the date and place of the meeting where the Business Plan will be completed and adopted.

Once this activity is completed, the group should proceed to the Evaluation of Unit VII, in the same manner as at the end of other Jornadas. This time, however, time should be allowed for each member to respond to the Individual Evaluation Form. Then, conclude with the group Evaluation.

GLOSSARY

Balance Sheet

A tool for general information that reflects the situation of an enterprise in a given moment, typically at the end of a year. Using the Balance Sheet we gather and share information about the Enterprise’s Assets (all the goods possessed by the enterprise), its Debts, and its Equity (the capital remaining after subtracting debts from assets).

Budget

An estimation or calculation of the expected expenses and revenue for a period of time (generally a year). The Budget is an important tool for planning, scheduling, control and evaluation of the operations of an enterprise. Normally the Budget is approved by the Member Assembly at the beginning of the year and its fulfillment is evaluated by the Assembly on a monthly or quarterly basis.

Distribution of Surplus

The distribution at the end of an accounting period of surplus generated in an enterprise during that period. In solidarity enterprises, the distribution of surplus is the means by which members are compensated for their contributions of productive factors, including remuneration for Labor, Capital and the C Factor.

Income Statement (Profit and Loss Statement)

A tool for accounting and information sharing that summarizes the operations of an enterprise in a given period (typically one year). It includes: revenues (the result of sales); expenses (costs incurred for production, administration, and sale of good and/or services), depreciation (the loss of value of assets over the period, counted as a cost); other income and expenditures; monetary corrections (gains or losses in value dues to inflation or deflation); and profits.

Interest Rate (on deposits)

The rate of interest paid by the bank or other financial institution on money the depositor makes available to the bank for a set period of time.

... (on loans)

The rate of interest paid by a borrower to a bank or financial institution for money borrowed for a set period of time.

Labor Management Responsibilities

The organizing and leadership activities and roles played by workers in a solidarity enterprise, implying certain special responsibilities that flow from the impact that their decisions can have on the operations of the enterprise and its efficiency. These management tasks and responsibilities imply a greater productivity that deserves recognition for the workers who do them, which should be reflected in their shares of surplus.

Profits

In standard economic terminology, profits, gains, earnings, and surplus are all essentially the same, expressing the positive difference between total revenues and total costs in a given period of time. In our understanding of solidarity enterprises, surplus and profits are different. We use the term profits for current accounts, as it is commonly used for calculating taxes. The main difference between profits in this sense and surplus is that calculations of profit are made by subtracting from revenues not just the payments to third parties but also compensation paid to members for their labor. This concept of profit is useful for comparing the solidarity enterprise to capitalist enterprises which, obviously, do not include remunerations for labor as part of their profit.

Remuneration of Capital

In solidarity enterprises, that portion of the surplus used to compensate members for their individual or collective contributions of capital. This remuneration is not a fixed rate paid on the amount contributed but is rather a “share of surplus” obtained in each period.

Remuneration of the C Factor

In solidarity enterprises part of the surplus is used to compensate or develop the C Factor for the important contribution it makes to the enterprise and its productivity. The rate of remuneration of the C Factor is determined by the members according to their own criteria and in the proportions they think best. The key criterion is that the remuneration be sufficient to stimulate the collective to maintain and improve its internal cohesion, that unity of consciences, wills, and feelings among the members of the solidarity group (members of the enterprise), which is the base of its creation and its special mode of being and operating.

Remuneration of Labor

In solidarity enterprises that part of the surplus that is used to remunerate members for their labor contributions. Remuneration of labor is not accomplished by paying a pre-determined fixed salary but as a share of surplus obtained in each period (year). Nonetheless, solidarity enterprises often pay anticipated distributions on a monthly basis (similar to salary, but the content is different), which is nothing other than a determinate quantity of money which can vary depending on the performance of the enterprise. At the end of the year, in light of the actual results the anticipated distributions are balanced against the shares of surplus going to each member.

Share of Surplus

The proportion of the surplus that goes to a member or factor of production as compensation for their contributions. The basic criterion of distribution is that the surplus goes to those who contributed to its generation, in proportion to their contributions.

Surplus

We use this term as a synonym for “gains” in the largest sense and distinguish it from “profits” which we use in a narrower sense. In solidarity enterprises, surplus is the final positive result that the enterprise obtains for the benefit of its members, normally calculated at the end of the fiscal year. This result is determined by the difference between the total revenues over the period and the total of payments made to third parties (external to the enterprise), such as rents, fixed costs, financial costs, purchases of raw materials, salaries paid to employees who are not part of the enterprise, payment of debts, taxes, etc. The surplus is used to remunerate and compensate members for their contributions of factors and to build the equity of the enterprise through reinvestment. Surplus includes remuneration for the labor performed by members, whether paid at the end of the fiscal year, or on a monthly basis in the form of anticipated distributions. It also includes money spent on investment in the enterprise, such as purchase of machinery, technological improvements, amortization of debt, inventories of supplies or products, etc. that imply an expansion of equity or of the enterprise’s productive factors. Surplus also includes the profits that are divided among the members in return for their contributions of capital or for any other ownership title.

Technological Content of Labor

The knowledge, information, skill, and special capacity that characterizes a particular labor activity and that when applied increases the productivity of that labor. More concretely, this refers to the technical and professional skills required for the performance of certain specialized jobs.

EVALUATION OF UNIT VII

This evaluation is to be done both individually and as a group.

Individual Evaluation

Each participant should answer the following questions in their notebook:

A. Circle the answer that best matches your experience.

My understanding of the content covered in Unit VII is:

Weak – Good – Excellent

My performance of the individual assignments in this Unit was:

Weak – Satisfactory – Very good

I consider my contributions to the group exercises to be:

Poor – Adequate – Outstanding

My participation in the organization and execution of the Jornada was:

Passive – Relatively active – Very active

I think my overall contribution to the group was:

Very little – Could have been better – Ample

B. Reflect on the following questions and summarize your answers in writing.

- Do I believe that the pay schedule we established for the different worker-members in our enterprise is just? Is it fair for each person, or have any members been harmed or others unfairly rewarded?

- Do I believe that the system of distribution of surplus that we have adopted is just and has the character of solidarity? Do I feel that all of us in the group are convinced that this is the right way to distribute surplus?

- We have now completed all seven Units of this manual: do I believe we are ready to make real everything we have learned? Are we ready to give our enterprise an official legal form and Business Plan?

Group Evaluation

Seated in a circle, the whole group discusses the following questions.

- Have we created a fair pay schedule for the different worker-members in our enterprise, that has the character of solidarity? Are we sure that we have not harmed or unfairly rewarded any member?

- Have we established specific criteria for determining the distribution of surplus? Do all members understand exactly how the enterprise will function in this respect? Are we all in agreement and convinced that this is the best system for distribution of surplus?

- Are we ready to formalize the legal structure of our enterprise, applying the criteria we defined in the course? Are we ready to elaborate our Business Plan?

- What is the state of our C Factor? Has it grown as we worked our way through the course, or has it stagnated or declined for some reason? Do we need to organize another Mitote?

Final Project #1

Elaboration of the Bylaws and Internal Regulations of the Solidarity Enterprise

WARNING: The following is a guide to elaborating the bylaws or internal regulations for a solidarity enterprise. This guide was prepared to help enterprises in the process of formation think about which of a variety of legal forms that are available in the country in which the enterprise is being created might be best suited to their size and characteristics.

Each country has its own laws regulating the formation of societies, cooperatives, and businesses. For this reason, this guide does not pretend to offer legal advice; it is only an instrument designed to help you gather and organize all the information normally required in order to acquire legal status for a society or economic organization.

The information you gather here should be delivered to an attorney or specialist who can guide the group with respect to the juridical form best suited to the enterprise, according to the laws of the particular country and the characteristics of the particular solidarity group.

We recommend that group members, having compiled the data required by this guide, seek the help of an attorney or legal expert who can help them determine whether it is best to create a legal entity or not and if it is, which of the available forms would be best suited to their purposes.

In any case, the form to be chosen remains the group’s decision, not the attorney’s. The attorney is there to assist the group, provide necessary information, answer questions and clarify confusing points. If the group chooses, the attorney can be tasked with drafting and editing the bylaws and carrying out the procedures for establishing the enterprise in conformity with the laws and procedures of the given country/state.

Enterprise Bylaws Structure

Article 1 About the Enterprise

Article 2 Objectives and Purpose

Article 3 Members

Article 4 Governance and Management Bodies

Article 5 Leadership Positions

Article 6 Ownership

Article 7 Changes to the Bylaws, Dissolution of the Enterprise, Conflicts among Members

Article 8 Internal Regulations

Article 1 About the Enterprise

- Date and location of the enterprise’s establishment.

- Full legal name of the enterprise, for government records.

- Common name or trademark to be used in promotion, etc..

- Legal form (workers co-operative, LLC, partnership, non-profit organization, etc.).

- Address for official correspondence.

- Duration of the enterprise (indefinite, or limited duration).

- Founding members of the enterprise. The following information should be provided for each member: full name, nationality, profession or title, marriage status, identification document, address.

- Official representative of the enterprise, member(s) of the enterprise with the right to represent the enterprise in negotiations, administration, and legal matters, and the right to use the official name.

Article 2 Objectives and Purpose

- General objectives of the enterprise as established by the founding members.

- Purpose of the enterprise: the economic activities to be carried out by the enterprise (detailed description of all the economic activities, production, sales, services, investment, etc. that the society can legally perform).

Article 3 Members

- Who can become a member.

- Requirements for membership.

- How to become a member.

- Obligations and responsibilities of members.

- Rights and powers of members.

- Revocation/withdrawal of membership.

- Penalties that members may suffer for failure to meet obligations.

Article 4 Governance and Management

- Governance and management bodies (for example, Member Assembly, Governing Council, Audit Committee, Management Council, etc.)

- For each body specify:

- Who will be on it.

- How members are selected/removed.

- What tasks the body performs.

- What are its specific powers and exclusive responsibilities.

- What powers the body can delegate and to whom.

- How often it will meet and how meetings will be announced, how members will be notified.

- Who can call a special meeting, how to call a special meeting.

- How voting will be done and the basic criterion (for example, one person one vote, percentage of ownership, etc.).

- Quorum for meetings and votes.

Article 5 Leadership Positions

- Positions held by one person (e.g., president, treasurer, general secretary, manager, etc.).

- How people are selected for each position (election, appointment, sortition, etc.).

- Powers and responsibilities of each position.

- Duration of the positions and how people holding them are replaced or removed.

Article 6 Ownership

- Sources of equity for the enterprise (e.g., dues and contributions from members, reinvestment of earnings, donations received, etc.).

- The amount of capital with which the enterprise is established (the amount of money to be used for initiating the enterprise and carrying out its activities).

- The percentage of the initial capital to be contributed by each member (the percentage of the total initial capital contributed by each member).

- The percentage of the surplus generated by the enterprise to be distributed to each member.

Article 7 Changes to the Bylaws, Dissolution of the Enterprise, Conflicts among Members

- The leadership body that can change or amend the bylaws;

- the procedures to be followed;

- the quorum needed.

- Circumstances under which the enterprise can be dissolved;

- who can make the decision;

- the procedures to be followed;

- the quorum needed.

- Continuation of the enterprise in the case of the death of a member. (E.g., the enterprise continues with the remaining members plus a representative chosen by the heirs or successors of the deceased member, who will only act to represent them in relation to matters such as distribution of surplus but without any administrative or other governance role.)

- Conflict between members regarding interpretation of the bylaws, their validity, the performance or non-performance by each member of their obligations under the bylaws, accountability of officers or representatives, etc.. (Use of an outside professional arbitrator, chosen by the members, some other mediation services, or the legal system.)

Article 8 Internal Regulations

- Identification of other aspects of group and enterprise functioning needing regulation.

- Organization of labor, assignment of tasks, hours of work, norms for performance of work, bonuses, incentives, penalties, etc.

- Other.

Final Project #2

Creation of a Business Plan for the Solidarity Enterprise

WARNING: The following is a guide to creating a business plan. It was designed to be useful for a wide variety of enterprises, from production to services, of different sizes and characteristics. Each solidarity group should adapt the outline presented here to their particular project, keeping what is useful and changing what is not.6

Structure of the Business Plan

1) Presentation of the group and the enterprise.

2) Description of the products and/or services to be offered, specifying their unique qualities and values.

3) Description of the potential market.

4) Marketing and sales strategy.

5) Business model and finance plan.

6) Organization of production.

7) Organization of sales.

8) Organization of management.

9) Partners and strategic alliances.

- Presentation

(Used to present the business plan to potential investors. It is also useful for explaining the enterprise to potential providers and clients. It provides a basic definition that can be used in leaflets, websites, or other promotional materials. It should include the following elements:)

- Name of the enterprise.

- Legal form.

- Legal representative.

- Date of establishment.

- About us (brief description of the members).

- Location (address and access).

- Our Mission (brief summary of the goals of the enterprise).

- Business Idea (brief summary)

- Our Products and Services

- What we produce (enumeration and basic description of the products and/or services the enterprise can offer).

- Current stage of development (specify what remains to be done to be ready to offer products and services).

- Production capacity (current possible monthly volume of production for each product or service)

- Quality of services and products (characteristics, functionality, technical specifications of products or services).

- Unique value proposition (needs met by the products, distinctive features or values, other details which explain how they differ from others offered on the market).

- Prices and conditions (list of prices, purchase conditions, guarantees, after-sales services, etc.)

- Potential Market

- Target markets for our products and/or services (identify customer segments by age, gender, geographic location, socio-economic level, etc.; or the enterprises, organizations, or other clients that might be interested in our products and/or services).

- Customer segments (make lists based on objective criteria for segmentation)

- Market size for each customer type or segment.

- Principal factors determining growth of demand for each segment.

- Most attractive market segment.

- Size of potential market (quantity of prospective customers and volume of demand).

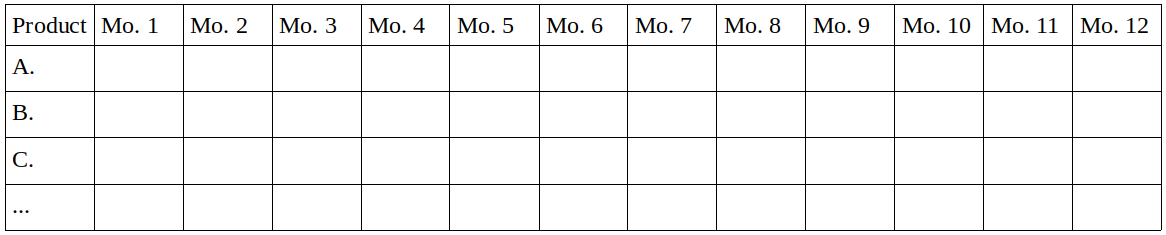

Expected volume of sales (for each product or service estimate the quantities to be sold each month over the course of the first year).

- Target markets for our products and/or services (identify customer segments by age, gender, geographic location, socio-economic level, etc.; or the enterprises, organizations, or other clients that might be interested in our products and/or services).

- Marketing and sales strategy

- Positioning of the enterprise and its products (specify how your enterprise and its products and/or services will be made known to potential customers. Describe in detail the plan for a launching campaign, identifying all means to be used.).

- Advertising and publicity to maintain and expand the customer base and the demand for your products and/or services. Specify the strategy to be followed for recruiting the desired number of customers and the cost involved:

- Channels for communication with potential customers

- Providers of publicity or advertising with whom you intend to work.

- Price policy (specify the price policy to be used in order to position your products in the market and expand demand, guaranteeing the expected profits).

- Business model and financing plan

- Revenue streams (it is not only necessary to have a unique value proposition for your products and/or services, you also have to specify the various sources of revenue, detailing each expected source and stream of revenue).

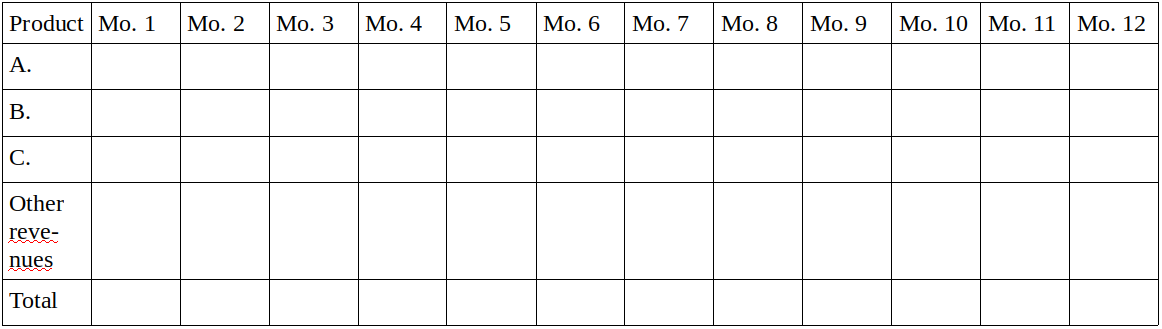

Expected revenues (calculate the monthly revenues based on the volume of sales defined above (3c) and the other sources of revenue).

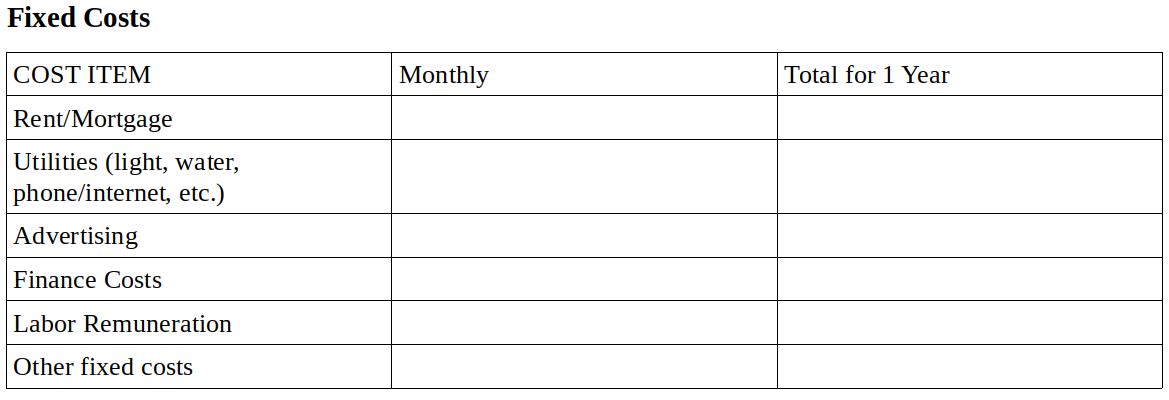

Cost items (specify all the fixed costs to be incurred by the enterprise in its regular operation and all the variable costs that depend on the level of production needed to satisfy the demand calculated in (3c) above).

Expected Income.

- Organization of Production

- Current state of development of the products and/or services (prototypes of products, previous provision of services, completed models and designs, necessary tools, sufficient workforce, sufficient supply of inputs or identified supply chains, etc.)

- Physical organization of the enterprise.

- Scheduling of production.

- Launching plan (specify all the activities necessary in order to launch the enterprise, including a calendar, principal activities and people responsible, landmarks and deadlines, linkages between activities).

- Organization of Sales and Commercial Relations

- Current customers and contacts (elaborate a list of potential customers, analyzing in each case the status of the commercial relationship and the modes of establishing and enhancing it).

- Organization of advertising and sales.

- Scheduling of sales and commercial activities.

- Plan for implementation (make a plan that includes all the necessary activities for improving sales, including a calendar, principal activities and people responsible, landmarks and deadlines, linkages between activities).

- Organization of Management

- Design the Enterprise’s Organizational Chart

- Describe the principal leadership functions and positions.

- List the people responsible for each function and how they are assigned.

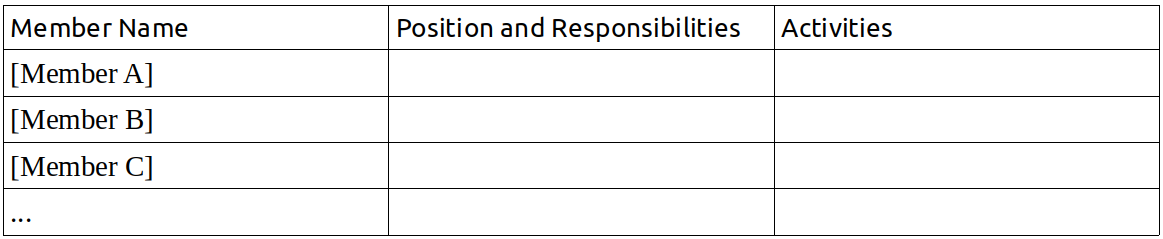

Organizational Structure

Complete the following table of responsibilities and activities for each member of the enterprise.

- Design the Enterprise’s Organizational Chart

- Partnerships and Strategic Alliances

It is important to identify all the contacts and relations that will be useful for the functioning and development of the enterprise, in both its commercial (suppliers, distributors, related enterprises, etc.) and social-institutional (public entities, non-profit organizations, community organizations, etc.) aspects. These relations need to be cultivated so it is useful to define the networks, coalitions, associations in which the enterprise will participate, as well as the opportunity to implement strategic alliances that will be most helpful to the enterprise and the people who make it up.

- 1“On Exactitude in Science.” Borges, Jorge Luis. https://www.openculture.com/on-exactitude-in-science-by-jorge-luis-borges

- 2See the Platform Cooperative Consortium https://platform.coop/, DisCO.Coop https://disco.coop/, Multi-stakeholder Cooperatives (article) https://thenextsystem.org/learn/stories/multi-stakeholder-cooperative, and FemProcomuns https://femprocomuns.coop/.

- 3Readers familiar with the “DisCO Manifesto” in which three categories of labor are recognized and remunerated – Livelihood, Love (Pro Bono), and Care – can see how the same purposes can be achieved in Razeto’s framework by treating Love and Care work as C Factor activities. https://disco.coop/manifesto/ [– MN]

- 4One of the original Rochdale principles. [– MN]

- 5Razeto’s language echoes the Mondragon principles which insist on the “instrumental and subordinated character of capital” and the “sovereignty of labor.” [– MN]

- 6Elements 2 - 9 should be subject to periodic assessment and revision by all the members as part of an ongoing strategic planning process. [– MN]

Citations