Unit I, Unit II, Unit III, Unit V, Unit VI, Unit VII

[Translator's note: In Unit III, the solidarity group began to operate as a work unit, considering the various factors of production – labor power, technology, management, materials, financing, and the C Factor – that will be needed in their enterprise and in what combination and proportion. Each member wrote a C.V. appropriate to the proposed solidarity enterprise and the group created a detailed Factor Canvas. In Unit IV, members determine which of the factors needed they can contribute to the group, creating a personal balance sheet and a making a proposal to the group. Having considered which factors it can develop through its own activity, the group reaches agreements with individual members about the factor contributions each will make and the terms on which the enterprise will accept them, an important step in the creation of their solidarity enterprise. – Matt Noyes]

UNIT IV

WHERE TO GET THE NECESSARY FACTORS

Member contributions and development by the group

Session 7

Plan

- Gather, welcome, ice-breaker, form a circle, choose a moderator for the meeting.

- Evaluation of Unit III.

- Each participant reads aloud their answers to the individual evaluation form from Unit III.

- Carry out the group evaluation as described in the group evaluation form from Unit III.

- Break, snack.

- “Reading Four.” (One or two people read out loud as others follow along in the text.)

- Questions for review and discussion. (Participants volunteer to answer one question each, raising their hands to speak. Other participants can add to their answers but it is best if nobody speaks twice before others have had a chance to speak.)

- Questions for the facilitator, exchange of ideas and free conversation on the theme.

- Suggestions for the Individual Task. (The facilitator will explain the content and purpose of the individual task, clarifying any issues and answering questions that come up.)

READING FOUR

Having created a solidarity group and identified a business idea, the members turn to the most important step in creating a solidarity enterprise: designing the basic equation of the enterprise – the “theorem” – on which achieving the efficiency needed for success depends.

Naturally, to define the theorem of an enterprise it is essential to know the quantity and quality of the factors that group can realistically hope to possess. We must, then, look at how solidarity enterprises obtain the factors they need. The distinction we made between internal and external factors leads us to two basic paths forward; the required factors can be acquired:

- By means of contributions from members of the enterprise themselves.

- By means of outside contributions, that is, from other people or organizations that decide to “place” factors in this enterprise.

But this distinction should be made more specific, in two senses.

On the one hand, it is possible for members, too, to provide factors to the enterprise “from outside” as it were, not as contributions to equity but as investments made in expectation of a return. If a member contributes a sum of money to the enterprise as a capital contribution it constitutes an “internal” factor, but if the money is provided as a loan that the enterprise must repay with interest in a specified time it is an “external” factor. In the same way, a physical space that a member provides, transferring ownership to the enterprise, becomes an internal factor. But if the member leases the space to the enterprise, it remains an external factor. Labor power itself can be integrated into the enterprise as a contribution or contracted externally in return for a wage or salary.

On the other hand, contributions made by third parties can be integrated into the equity of the enterprise, if they are made in the form of donations. But, if they are provided to the enterprise for a limited time, in return for periodic remuneration, they are considered external factors. If those external factors are amortized by the enterprise, they will gradually cease to be external and will in this way come to be internal. For example, financing obtained via a loan, or materials obtained through a lease cease to be external if the debt is canceled or the leasing contract is fully paid off by the enterprise.

The exact understanding of which factors are internal and which are external, of the distinct forms in which factors provided to the enterprise by members of the solidarity group and/or third parties are integrated, and the implications that these different possibilities have for the functioning of the enterprise is of vital importance for the creation and success of a solidarity enterprise. We must then take the necessary time to examine this question deeply, considering all the alternatives.

The associative enterprise based exclusively on external factors.

Theoretically, an associative and solidarity enterprise can be created exclusively with external factors. In fact such solidarity enterprises exist, and there are even authors who have recommended this model as the most suitable, under certain conditions. So, we should consider this possibility carefully.

Naturally, in order to create a solidarity enterprise of this type it is necessary that someone be willing to make the required investment. It could be the State, or a private entity or non-profit foundation that provides the resources.1 Certainly, creating a solidarity enterprise this way can enable the solidarity group to get access to resources; nonetheless there are certain problems to be considered.

If it is a matter of a loan on which interest will have to be paid the problem lies in the large portion of revenue that will have to be set aside for that purpose. Unless the enterprise can count on its own, internally sourced, factors, it will have to pay for all its factors directly or indirectly (servicing the loan) at normal market prices (or standard interest rates). As a result the enterprise is obliged to operate with a strict logic of maximization of monetary profits, risking the loss of its rationality of solidarity. And if, in order to obtain credit, the enterprise has had to provide guarantees that compromise the equity or the incomes of the members, the risk involved is terribly high. If the enterprise functions successfully, it means that the solidarity group is working with high efficiency… for the benefit of the person or entity that provided the financing. For this reason, this alternative, having been considered, should be discarded.

If the contribution of factors is made as a kind of grant, subject to the achievement of determined objectives established by the party making the contribution, with the enterprise retaining ownership of the resources donated (for which it does not pay), the obvious problem is that the solidarity group might fall into a relation of dependence with respect to the patron or funder of the enterprise, which will certainly exercise close control and oversight. Moreover, as the enterprise is not really owned by the solidarity group and its members it is unlikely that the members will be willing to invest money from their earnings in order to expand the factors available to an enterprise that does not really belong to them. The Yugoslav model of self-management faced this problem; it was the State that made the initial investment and provided the necessary factors for production and growth. The workers self-managed with some solidarity, but with very relative autonomy, and, lacking the right incentives to develop the enterprise, low levels of efficiency. This alternative, too, should be discarded.

There do exist experiences in which a solidarity enterprise is created with funds contributed by a “not-for-profit” entity which transfers ownership of the enterprise to the members when they have demonstrated the capacity to manage and develop it successfully. In this case, the solidarity group has a large incentive to contribute as much as possible to the enterprise and to manage it with high efficiency. Nonetheless, in fact, donations made to promote the creation of solidarity enterprises are often used in a different way: the contributions are oriented towards already existing solidarity enterprises or those in formation, in which the members have already made all the contributions they can. The donation is made to supplement the provision of the necessary factors.

Whether or not the enterprise has access to donations or credit, we can draw this conclusion:

It is essential that the largest and best contributions of factors to the solidarity enterprise be made by members investing their own resources.

The advantages to the enterprise are clear: direct costs are reduced, as are the risks, autonomy in management and operations is increased, and the possibility of operating with a coherent solidarity rationality is better assured.

So, in the case of solidarity enterprises, we can say that in order to assure the success of the initiative, members must generously contribute all the factors they possess that can enhance the productivity of the enterprise.

Each person possess multiple and various factors, of the six types: labor power; tools, equipment and other useful materials; knowledge, know-how, skills and creativity (the technology factor); their capacity for organization and leadership (management); payment of dues, savings, ability to get loans, to loan money themselves or to forgo collection of remuneration (finance); and their spirit of solidarity, their capacity to generate trust, fellowship and group integration (C Factor). All of these can be brought to the enterprise from within, as it were, providing it with as many of the necessary factors as possible.

Determining which factors members can provide is the first task to be done, before thinking about obtaining loans or donations. The possibility of the latter is strongly conditioned by, and often proportional to the former. When someone makes a donation or decides to make a loan to a solidarity group, it is because that group inspires sufficient confidence and seems likely to generate good results. It makes sense: why should an external person or entity put their trust in an initiative whose members themselves have not demonstrated their own commitment by making contributions, in which they do not have “skin in the game,” in which members have not made the contributions they alone can make?

Having clarified all this, we should still be aware that the decision of each member to contribute factors to the enterprise should be an economically rational decision. This basically means that the member can reasonably expect the contributions they make to the enterprise to benefit them, that is that the expected benefit exceeds the sacrifice implied by giving up that which they contribute to the shared enterprise. We should never forget that in the solidarity economy enterprises exist and work for people, and not the reverse as in the capitalist economy.

It is necessary, then, to evaluate as exactly as possible the sacrifices implied in the contribution of factors each member makes, as well as the benefits they might obtain. To this end we need to know and be comfortable with some key concepts.

Opportunity Costs and Lost Earnings

One often hears economists speak of opportunity cost, the sacrifice of income that can occur when a person or institution contributes to an enterprise some factor in their possession which is then no longer available to be used by the individual. For the person making the contribution, the opportunity cost can be measured by the income they would have obtained if, instead of contributing the factor they possess to the solidarity enterprise, they had offered it on the market and it had been employed in some other enterprise in exchange for money. The opportunity cost is the sacrifice of those earnings, which can’t be obtained because you contributed the resources to the enterprise. So, for example, the remuneration that you forgo, having decided to leave your job to work in the solidarity enterprise, is an opportunity cost. Likewise, the interest on money invested for a fixed term which is lost when those funds are used to finance the solidarity enterprise, or the rent on a property that one ceases to receive having turned it over to the solidarity enterprise.

But it should be noted that the opportunity costs can differ from the income that the factor could generate in the market, since there are usually costs associated with use of the factor and the acquisition of that income, which should be discounted when quantifying the opportunity cost. For example, from the remuneration of labor one should discount the cost of transportation, if this is no longer needed when working at the solidarity enterprise. The same applies to taxes paid on rental income and so on. On the other hand, there are also benefits that are lost when removing a factor from its current use. Those too should be quantified and in that case added to the income as their loss also implies an opportunity cost.

It is very important to make the most exact evaluation possible of the opportunity costs incurred when moving factors from their current use to use in the solidarity enterprise since the enterprise should provide net benefits to those who make contributions. For the individual member it only makes sense to contribute factors that they possess to the enterprise when the opportunity costs are lower than the productivity to be gained by the enterprise, from which the member can benefit in proportion to their contributions. It is the job of the enterprise to reach sufficient efficiency in the use of the factors contributed by members that its productivity exceeds the opportunity costs implied in moving the factors from their previous use.

It is important, now, to distinguish the actual and effective income which the contributor ceases to receive when a factor that is removed from its previous use or investment and placed in the enterprise, from lost earnings. Lost earnings consist of income that might possibly be obtained if a factor currently unused, and thus not generating income, were to be employed. From this point of view, the productive occupation of factors that the members are not using should be beneficial for them.

That said it is important to add that the decision to contribute a factor to the solidarity enterprise should not be based purely on a monetary calculation of opportunity cost and lost earnings. The solidarity enterprise offers other benefits to its members that are not to be evaluated in monetary terms. In Unit 2, we spoke of the fulfillment of objectives that transcend the strictly economic, such as the community meeting the shared needs, aspirations, and desires of its members; these considerations should also be taken into account when making this decision.

Nor should the economic calculation of costs and benefits stand in the way of personal generosity, or group solidarity. Knowing they are part of a common project in which benefits will be shared, members may make generous contributions to the enterprise, even if they involve short-term sacrifices of income or profit. They do this because they know that in the long run the gains they share in the spirit of solidarity, not all of which can be measured in money, can be enormous.

Still, and even if people are ready to make contributions for which the opportunity cost is higher than the expected personal benefit, it is important that the opportunity costs be rigorously calculated. On the one hand, because it is always helpful to know – and for everyone to know – what each member’s participation implies. On the other hand, it is important for the enterprise to have all the information necessary to allow members to evaluate its true economic efficiency. As we will see in Unit 6 where we examine the economic organization of the enterprise (its ownership structure and the distribution of surplus), it is essential to have an exact valuation of the contributions made by each member.

Five ways factors can be contributed to the enterprise.

There are different ways in which members can make factor contributions to the enterprise, with significant impacts on ownership structure, cost composition, operational efficiency, use and distribution of surplus, strength of group cohesion, and more. As participation in the enterprise is a free and voluntary decision that each member makes, so the contributions they make and the way they make them depend on the sovereign decision of each member. To make appropriate decisions, it is important to know the difference and distinguish between the five principal ways in which members can contribute factors to the enterprise:

Donations

Members of a solidarity group can give or donate to a solidarity enterprise factors in their personal possession. They donate their labor power when they do voluntary or unpaid work; materials when they contribute tools, furniture, the use of a locale, etc. without compensation; technology when they contribute and share their knowledge and teach others in the group; management when they bring their organizing, administrative, and leadership capacity, without expectation of recompense; financing when they offer no-interest loans or access to credit; and the C Factor when they contribute everything that favors group integration, conflict resolution, relations with the community and other organizations, etc.

Contributions to Equity

Members of a solidarity group can contribute factors by transferring their property, so that it becomes part of the equity of the enterprise; but these contributions are not made as gifts or donations. They have a specific monetary value that is recorded in a member contribution account. In this way, the contributing members come to be owners of the enterprise in proportion to the sum of the values of the contributions each of them makes. Based on, and in proportion to, these contributions the members acquire certain rights with respect to the enterprise, basically the right to participate in the distribution of profits in proportion to the contributions made and to recover the value of their contributions if in the future they decide to withdraw from the enterprise. Money dues and capital contributions, materials transferred to the enterprise, rights to patents and inventions, are all of this type. Their value is calculated at market prices.

Non-Equity Contributions of Use and Usufruct

Members of the solidarity group can also contribute factors without transferring ownership to the enterprise, offering only their productive use. The contributed factor remains the property of the member but is used by the enterprise, which benefits from its usufruct. These contributions can be made in two ways:

- as donations members make to the enterprise which can use and benefit from them for a specified or unspecified period of time (normally in this type of contribution the contributing member is guaranteed the maintenance, repair, or compensation for damage, loss, or other costs implied by use of the factor);

- as non-equity contributions reported in the member’s account, entitling the member to a proportion of equity and profits. In this case, what is valued and recorded as a contribution is not the factor itself but the time during which it is used by the enterprise. For example, if a locale, a machine, or a fixed amount of labor is contributed, it is valued as a contribution equivalent to the rent or salary that would be paid, and this amount is entered into the books as a member contribution, with corresponding rights to a proportion of equity and profits.

Compensated Contributions

Members of the solidarity group can make factor contributions without those contributions being recorded in their capital accounts and without being paid as external factors, but in return for some compensation from the enterprise, the solidarity group, or other members. Such contributions are made according to an agreement between both parties and can take various forms and characteristics. For example, a contribution of factors can be compensated through certain services, such as child care, training, certain honorific titles, the right to use certain of the enterprise’s resources, etc. A very interesting way to stimulate compensated contributions, especially effective in the case of large groups, is through the circulation of solidarity units of account, or the emission of alternative currencies internal to the enterprise.2

Contribution of Paid External Factors

Members of the solidarity group can contribute factors to the enterprise for a given period of time on the basis of contractual terms or at market rates, those contributions being remunerated at pre-established prices. Using this form, members can provide the enterprise with credit, rentals, sales, leasing, etc. For the enterprise that needs to seek external factors, it may be more convenient to rely on external factors provided by members than by third parties, assuming that, naturally, they are provided at the lowest cost for which they might be obtained on the market.

As we have seen, members of the solidarity group have various options when it comes to contributing factors to the enterprise. But some factors that are better offered in one form than another. The C Factor, to be sure, should always be contributed as a gift or donation.

Technology and management factors are also especially suited to donation, with members sharing know-how and organizing capacities with all the members. Nonetheless, management and technological development can require special dedication of some people who contribute their skills professionally, making that their primary function in the enterprise. In such cases, it is appropriate that their contributions be made in the same form as other contributions of labor power, which we shall examine momentarily.

As for the finance factor, the most appropriate form seems to be an equity contribution. This is also true for contributions of material means of production, although in this case the non-equity contribution of use and usufruct may also be appropriate.

Contributions of the factor labor power in solidarity and associative enterprises deserve special analysis.

Treatment of labor power.

Labor power is inseparable from the people who do the work. As a factor that is always personal in this way, it can not, strictly speaking, be considered a factor belonging to the enterprise. Nonetheless, in the case of solidarity enterprises in which the members are the workers, the organizing subject of the enterprise – the solidarity group – constitutes the principal source of labor power on which the enterprise relies. As the enterprise belongs to the solidarity group, the group identifies itself with the enterprise in which it works, and in this sense the labor power becomes a factor belonging to the enterprise. Said another way, workers invest their labor power in their enterprise which then becomes one of their principal assets.

But there are various ways for workers in a solidarity group to incorporate their labor power into the enterprise, each resulting in a different way of treating the factor, economically speaking.

The choice is basically the following. If the workers set for themselves a fixed compensation, monthly or with another periodicity, that the enterprise is obligated to provide them, the effect is the same as if their labor power were an external factor. For the enterprise, labor compensation constitutes a fixed cost. This is not the best way to proceed because the enterprise can find itself obligated to make payments that exceed its capacity and may perhaps even fail.

The other way to compensate labor, which treats labor power as an internal factor, is through distribution of surplus generated by the enterprise in its operations. In that case, the compensation is not a fixed quantity but a percentage of the surplus. If the enterprise has good results, the compensation is greater, and it the results are poor, the workers have to settle for what their enterprise is able to generate.

This seems to be the most coherent way to make and compensate labor contributions. But there is a problem: workers need regular income in periods that are much shorter than the usual period used to calculate income and loss, typically the fiscal year. This can be resolved through monthly payments to workers that are considered to be anticipated earnings, distributions made in anticipation of the annual results that can be fixed or variable according to the perception of the condition of the enterprise. These anticipated earnings can also be partially fixed, with a guaranteed indispensable minimum, and a portion that increases incrementally in relation to the performance of the enterprise, in anticipation of a larger amount of surplus, for example.

Creation and development of factors by the solidarity group.

Once all of the factors that can be provided by individual members of the solidarity group have been identified and the contributions have been made, the enterprise may still lack some factors. How to obtain them? In Unit V we will examine how the solidarity group can obtain and integrate external factors contributed by third parties. But before that we must see how, in addition to individual contributions, the solidarity group as such can also provide its own factors, creating and developing factors through an active process.

In effect, there are elements and factors that the solidarity group can create or obtain through its own effort. For the success of the enterprise the group should explore this possibility in depth and make every effort in this direction, because the more factors available to the group when it begins to function, the lower will be its costs and the greater the surplus and profits produced. Which factors can the group create and develop for itself, and how?

Any of the six factors can be developed in this way. The labor power of the group’s members can be improved and upgraded, increasing its productivity, through training and a kind of apprenticeship in which members teach each other.3 The technology factor can be developed with study, application of group creativity and innovation, and reciprocal exchange of know-how. Some furniture, tools, instruments and other material means of production can be fabricated by group members and work teams. Management and administrative capacity can be developed through better group organization, improving internal communication, joint execution of administrative tasks, leadership and management training, etc. Some amount of financing can be secured by carrying out fund-raising activities like raffles, campaigns, community events, etc. And of course, the group can always expand its C Factor, growing in solidarity and cooperation and deploying active processes to broaden its social relations with the community and surrounding social environment.

Since we are thinking about creating a solidarity enterprise, it is decisive that the group make an effort to create and develop to the maximum its own collective resources and capacities, before recurring to external sources. This is as important as the personal contributions made by each member, or more so, since it favors the integration of the group, reducing costs and deepening the commitment each and all make to the common work.

INDIVIDUAL TASK #4

To be done after the seventh session.

- Study the Glossary at the end of Unit IV.

- Answer the “Questions for Review and Discussion #4” in writing in your notebook.

- Write your “personal balance sheet.”

Questions for Review and Discussion #4

The following questions should be answered individually, in writing. Each participant will later share their answers during the group work, allowing for evaluation and correction of the answers by comparing them with the answers of other members and ensuing discussion.

- What are the principal ways a solidarity enterprise can obtain the necessary factors of production?

- Is it possible to create a solidarity enterprise solely with external factors?

- Why is that not a good idea?

- Why is it better for the members of the enterprise themselves to contribute most of the factors?

- What is meant by “opportunity cost”?

- In the reading, what is meant by “lost earnings”?

- What are the five main ways members can contribute factors to the solidarity enterprise?

- What is a member contributions account? What is it important to calculate and record this information?

- What are the ways in which members of a solidarity enterprise can contribute their labor power?

- What is the most appropriate way to treat contributions of labor power in a solidarity enterprise?

- Why is it important that the solidarity group itself do as much as possible to create and develop needed factors through group activities and shared effort?

How to make a “personal balance sheet.”

The purpose of this task is to determine exactly which factors each person possesses, their possible utility and productivity in the solidarity enterprise, and the member’s willingness to contribute the factors the possess, taking into account potential opportunity costs and lost earnings.

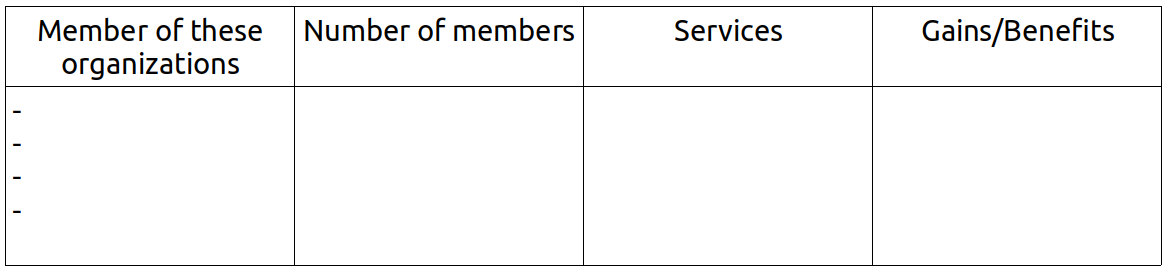

We call the analysis produced in this task a “personal balance sheet” because it resembles the information banks often demand of potential borrowers in order to evaluate their credit worthiness. In our case, the “personal balance sheet” deals with more than the usual aspects and is produced using a form that is structured differently. Each person should complete the following form:

Personal Balance Sheet

A. Personal information4:

-

- Full name:

- I.D. type and number:

- Mailing Address:

- Work Address:

- Email Address:

- Telephone:

- Birthdate:

- Nationality:

- Highest level of education completed:

- Marriage status:

- Number of dependents:

Full name of spouse or partner:

B. Labor Power

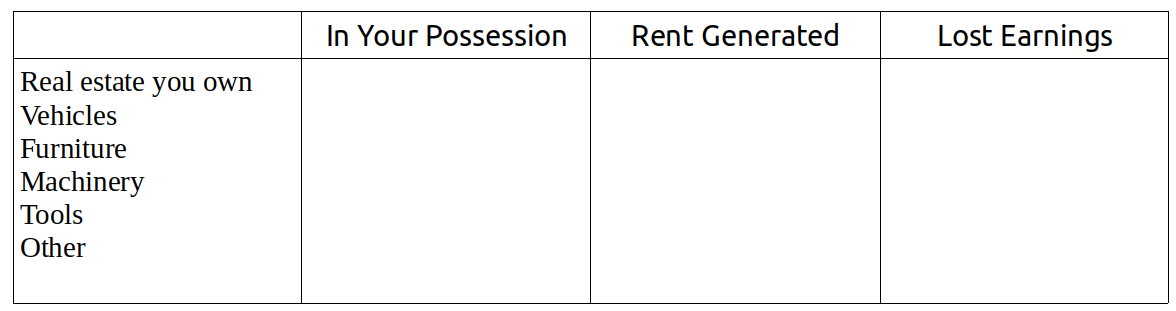

C. Material Means of Production

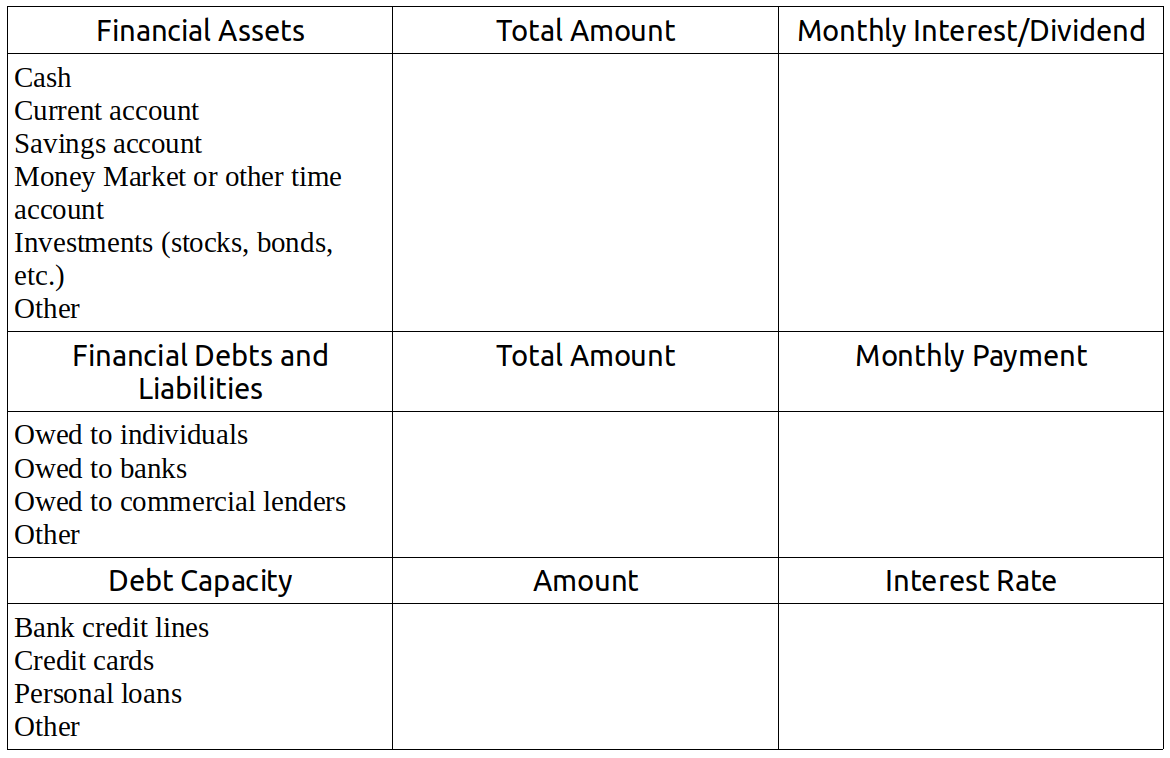

D. Finance

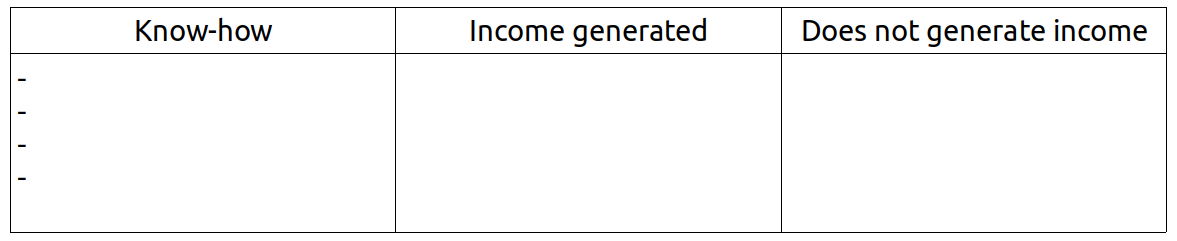

E. Technology

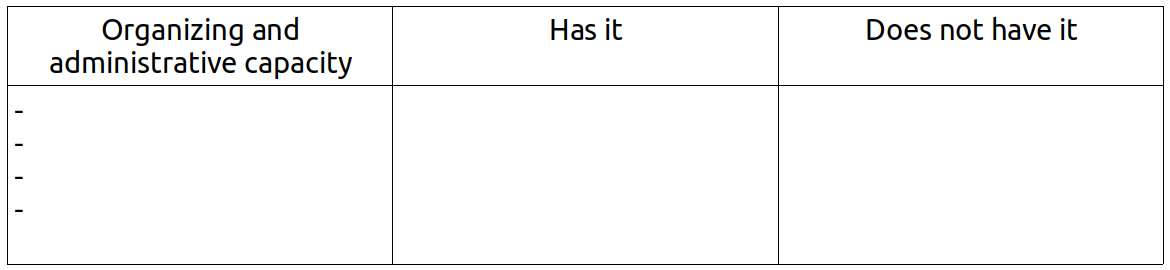

F. Management

G. The C Factor

Session 8

Plan

- Gather, welcome, thematic game, form a circle, choose a moderator for the meeting.

- Reading and commentary on the answers to Questions for Review and Discussion #3. (If the group is large, each participant will read only one or two responses.)

- Exercise #7. Sharing Personal Balance Sheets.

- Break, snack.

- Exercise #8. Planning the Development of Internal Factors.

- Assignment of Individual Task

- Reading and Organization of Jornada #4: “Deciding to Contribute.”

Exercise #7

Sharing Personal Balance Sheets

Explanation

In the creation of a solidarity enterprise it is important that all members understand as clearly as possible the economic situation of their fellow members. This mutual knowledge has various meanings. On the one hand, it favors the concrete development of the C Factor, facilitating communication, increasing mutual trust and enabling transparent human and economic relations. On the other hand, knowledge of each person’s situation leads to awareness of the needs that the solidarity enterprise should help meet. And finally, it helps the group identify the contributions that each member can make to the enterprise and what the solidarity group can expect of each person. This exercise is designed to help build this awareness.

The Flow

- Taking turns, group members read aloud their respective personal balance sheets and explain with some detail (as much as is needed to understand the point) each of the different elements.

- After each presentation, the other group members can ask questions about points that were not sufficiently clear. It is important not to interrogate people about their personal situations in a way that violates their privacy or intimacy. The level of detail of the answers should be determined by the member who is presenting, without any group pressure.

Once all the personal presentations have been made, the moderator can open a discussion with the purpose of analyzing the economic situation of the group as a whole, the skills, potential, limits, etc. of the solidarity group.

Exercise #8

Planning the Development of Internal Factors

Explanation

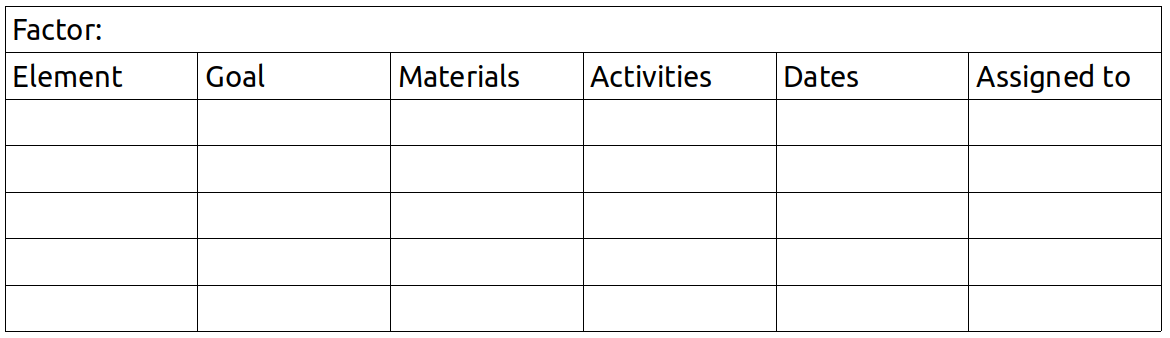

The solidarity group already knows which factors it needs to create the enterprise. They also know that the more factors contributed by the group itself, the greater the chances of success. Creating a solidarity enterprise implies planning the development of all the factors that the group itself can create or enhance through its own efforts, work, and study. In this exercise members identify as specifically as possible the factors that the group can develop internally, prior to launching the enterprise, and create a concrete plan of activities to do so.

The Flow

- Post the “Factor Theorem” canvas created in the previous jornada (with the index cards indicating all the indispensable elements for creating the enterprise) somewhere where it is visible to all.

- Discussion proceeds factor by factor, in the following order: labor power, materials, technology, management, financing, and the C Factor. The group reflects on each factor and discusses the possible ways to develop it and the means needed to do so.

- After general discussion of how the group can develop a factor, the next steps are to see if it is possible, and how to contribute to the creation or development of each elements identified on the corresponding cards.

On a flipchart or board, the group plans the development of factors, identifying for each element of a factor (noted on cards): the goal to be met, the means to used in meeting it, the relevant activities, the deadlines for completion, and the people to whom it is assigned. In this way, for each factor a planning table is drawn up:

- After completing the analysis of the six factors and all the cards, the planning tables are revised and a “development plan” summarizing the combined factors is made, in which the goals are integrate, realistic means, activities, and dates are determined, and personal responsibilities are fairly distributed.

- Each participant records in their notebook the “Development Plan for Internal Factors” highlighting their personal responsibilities. The fulfillment of this plan will be evaluated in the next session of the manual at which point necessary adjustments can be made.

Jornada #4

“Deciding to Contribute”

What is this practical activity about?

Having studied Reading 4, everyone now knows the importance of individual member contributions of factors to the solidarity enterprise as well as the way in which these contributions can be received by the enterprise.

The objective of this jornada is to identify in concrete terms which of the factors considered necessary for the enterprise will be contributed by members of the solidarity group.

In order for a necessary factor or element to be contributed by a member two decisions must be made: first, the person who possesses the factor decides whether to contribute it, under what conditions and in which of the forms we have considered; second, the solidarity group decides whether to accept the contribution in the form and under the conditions proposed.

In this jornada both decisions must be considered and when they match or agreement is reached, it is understood that the member will actually contribute the factor to the enterprise.

Which aspects should be taken into account, by the group and by each member, when deciding whether to offer/accept contributions of personal factors?

In the creation of the Curriculum Vitae and the Personal Balance Sheet, and in exercises 5, 6, and 7, the members of the solidarity group carried out a thorough assessment of the factors they possess. They also identified the combination of factors needed by the enterprise they hope to create, in the jornada “The Theorem,” including an estimate of the quantity and quality each factor needed, as well as the desired level of productivity.

All of this is fundamental information when it comes to making decisions with respect to the factor contributions to be made by members of the solidarity group. Not all the factors in members’ possession are necessary or useful for the enterprise and members may not be willing to contribute all the needed factors that they possess.

It is possible that members will want to contribute factors or elements that the solidarity group does not need, or that the group is not ready to accept them on the terms on which the member offers them. It can happen, for example, that a member owns a factor that they wish to contribute as equity, but values it at a level that that the group feels is excessive or is not viable for the enterprise. Inversely, it can happen that the enterprise needs a factor that a member has but is not willing to contribute, due to the excessive opportunity cost it implies.

The process of identifying possible member contributions to the enterprise is delicate, because the desires and interests of each person need to be taken into account along with the needs and interests of the group and the solidarity enterprise. This process, then, has to be carried out with great transparency and the best C Factor, comradeship, and mutual trust that the group can muster. Nonetheless the theorem of defined proportions, which guarantees efficiency, must not be ignored. (Here we should caution that like other factors it is possible for an enterprise to have an excess of the C Factor, which unbalances the other factors. Such would be the case, for example, if the group, motivated by the desire to help a member, accepted their contribution of certain factors in a greater quantity than needed or accepted factors of insufficient quality.)

It may also happen that various members have and wish to contribute the same factor and that the resulting quantity is too much for the enterprise to handle. For example, the enterprise could need fewer hours of work that those that members are offering, or various members might offer as equity contributions multiple tools of a certain type when the enterprise needs only one. In these cases the question is which factors to accept and which to decline, based on what seems best for the enterprise, but keeping in mind that it is important to maintain a good balance among the contributions made by each member.

What are the activities to be done in this jornada?

Deciding to Contribute is a three part process:

a) Preparation and planning (this is to be done in the seventh session).

b) Doing the assigned individual task.

c) A day (jornada) of group work.

What is the individual assignment?

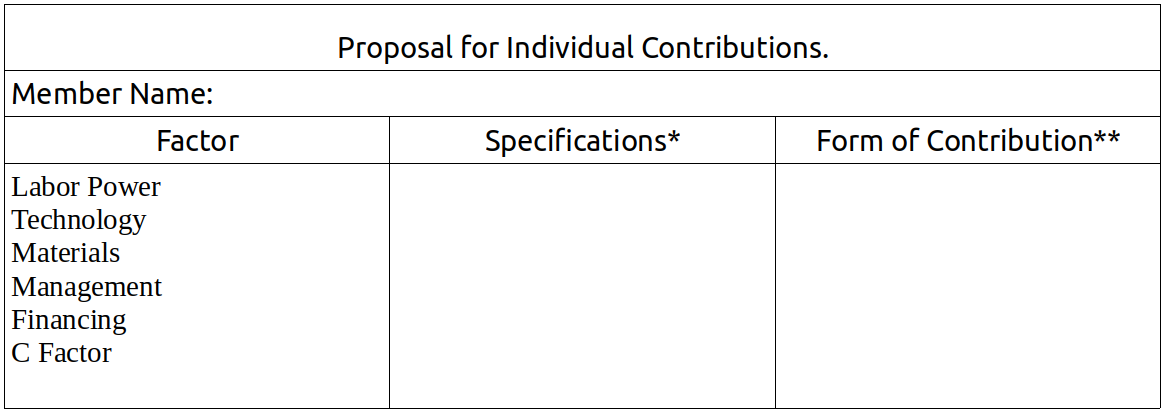

Each member of the group should come to the jornada with a clear understanding of the factors they possess, those they are willing to contribute to the group, and under what forms and conditions they are prepared to make the contribution(s). The individual task consists of writing a detailed proposal of the factor contributions they would like to make to the enterprise. During the jornada each person will present this information to the group so that the group can make collective decisions about whether to accept the contributions that each member proposes.

To write the proposal for individual contributions, each person should review their C.V. and their Personal Balance Sheet and complete the following form.

* The specifications are quantitative and qualitative. Specify age, brand, features, length of time it is available, and in general all the data that will help the group understand the value and productivity of the factor.

** The form of contribution should specify the conditions under which the factor is being offered to the enterprise. The alternatives are: a) donation; b) equity contribution; c) compensated contribution; d) non-equity contribution with right to use and usufruct; e) contribution for fixed compensation. (Indicate the conditions using the corresponding letter and provide details about the conditions, estimated value, etc.)

What should members bring to the jornada?

- Each person will bring their Curriculum Vitae, their Personal Balance Sheet, and their Proposal for Individual Contributions.

- The group symbol and logo design.

- All the materials from Exercises 5, 6, 7 and 8 in addition to the materials from Jornada #3, The Theorem.

- A flipchart.

- A large blackboard or other board for the canvas.

- Plenty of index cards (10cm x 20cm) in six colors.

Updated account information (personal and group).

How should the jornada be done, what is the plan for group work?

This jornada is essentially a work session that can be done in about four hours, though the group may decide to add other activities that they think would be good to include.

The jornada follows this plan:

- Gathering, welcome, thematic game. Installation of the group symbol in an appropriate place. Selection of a moderator for the meeting, as well as a “canvas manager” (person who manages the bulletin board or display used in the activities), and a note-taker.

- Set up the materials from Exercises 5, 6, 7, and 8, in addition to the materials from Jornada #3, The Theorem.

Prepare the canvas, using this layout:

- Activity 1. Offering contributions.

- Break and Snacks

- Activity 2. Accepting contributions.

- Activity 3. Making Decisions.

Contents of Activity 1

All members take a short time to write down each each factor they wish to contribute on an index card of the color corresponding to one of the six factors, as well as a second card of the same color describing the form and conditions of the contribution.

Taking turns, each participant presents their Proposal for Individual Contributions to the group and affixes their cards to the canvas.

Contents of Activity 2

Once all the participants have presented their proposed contributions, the group examines the usefulness and suitability of each for the enterprise, given the conditions and forms offered in each case. This analysis will enable the group to decide which factors to accept with an idea of how to integrate them into the solidarity enterprise.

This is a very delicate activity which should be undertaken with focus and careful attention. The analysis of each offer, about which a decision will later be made, should be done with transparency and maximum clarity, keeping in mind the enterprise and the common good of the group as well as the needs and interests of each member. In this sense, the group should be extremely careful in its analysis, and each member should offer their opinion with total sincerity and responsibility, for the good of the group and success of the enterprise. It is possible that differences of opinion will emerge at this phase, due to different judgments of the needs of the enterprise and the quality and productivity of the factors offered. Treating each opinion seriously and with respect, the conversation should focus on being as objective as possible, being careful to maintain the C Factor that should exist in the solidarity group.5

The “Theorem” canvas made in the previous jornada , which has a detailed categorization of the factors needed by the enterprise, is an important element that will help participants maintain the objectivity of their analysis. Referring to the “Theorem” canvas each person can see if their desired contribution or that of another fits with the group’s priorities. The canvas should be displayed somewhere where everyone can see it and use it to compare the factors offered to the factors already determined to be necessary.

In this analytical activity the group can propose changes to the conditions and modes in which members desire to make contributions, and each member will determine if the group’s proposals are acceptable or not. This can give rise to a kind of “bargaining” between the group and the individual members. Obviously, it is important to guarantee all members equality of opportunities and equity in treatment by the group.

Contents of Activity 3

Once the analysis of the offers has been made and the group has determined the utility and suitability of each, the time has come to decide whether to accept or reject them.

In this phase, and keeping in mind the analysis of the totality of factors offered by members and those needed by the enterprise, decisions will be made.

Each decision about the contribution of a factor and its integration in the enterprise requires the explicit enunciation of two converging decisions: that of the group, which decides whether to accept or reject a factor, and the individual, who decides whether or not to make the contribution. For each case (specific element), the group decision will be announced first, detailing the conditions, specifications and form of contribution that they feel are necessary, followed by the announcement of the individual’s decision to agree or disagree with the group’s decision.

All the decisions should be recorded carefully, in detail, on the canvas and by each member in their notebook.

The jornada is complete when each person and the group have defined exactly which factor contributions each member will make, and on what terms, when the time comes for the group to establish the enterprise.

GLOSSARY

Alternative currencies

Money or credit issued by associated economic subjects that circulates within groups conducting exchanges and barter on the basis of mutual trust.

Capital contributions

Member contributions in the form of money, materials, or any other factor of monetary value, that form part of the equity of the enterprise.

Cost-benefit analysis

The quantitative and qualitative estimation or evaluation of the costs and benefits expected from an economic activity over a determined period of time.

Leasing

A lease is a contract for the right to use an economic asset in exchange for a periodic fixed payment, implying the final transfer of the property upon completion of the payments. If the payments are not completed, the asset remains the property of the person making the contribution.

Lost earnings

The income or economic benefit that an economic asset could generate but is not being obtained because the asset is not being used.

Net profits

The global sum of economic profits generated in a given period minus all the costs and payments that must be made to third parties.

Opportunity cost

A term normally used to designate the sacrifice of income and other benefits implied by the application of an economic asset to a new use.

Rational economic decision

A decision is considered economically rational when it is made with the criterion of maximizing and optimizing income or profits in relation to costs or sacrifices.

Self-management

The system of management in an economic unit in which the workers collectively assume responsibility for management and administration.

Solidarity accounts

Quantitative registers of economic values transferred by some subjects to others within solidarity groups or circuits.

Usufruct

The right that an economic subject has to use an economic asset for their benefit and appropriate to themselves the benefits generated through its utilization.

EVALUATION OF UNIT IV

This evaluation is to be done both individually and as a group.

Individual Evaluation

Each participant should answer the following questions in their notebook:

A. Circle the answer that best matches your experience.

My understanding of the contents covered in Unit IV is:

Weak – Good – Excellent

My performance of the individual assignments in this Unit was:

Weak – Satisfactory – Very good

I consider my contributions to the group exercises to be:

Poor – Adequate – Outstanding

My participation in the organization and execution of the practical activity (jornada) was:

Passive – Relatively active – Very active

I think my overall contribution to the group was:

Very little – Could have been better – Ample

B. Reflect on the following questions and summarize your answers in writing.

- Did I create a Personal Balance Sheet that was properly structured, true, and complete? Did it help me discover and value the productive factors in my possession?

- Do I feel that the factors I possess can be useful to the solidarity enterprise we are hoping to create? Am I comfortable with the contributions I offered to the enterprise and those which the solidarity group accepted?

- Do the agreements on the development of factors that we came up with in the solidarity group make sense? Are there other elements that we could develop as a group?

Group Evaluation (to be done in the next session)

Seated in a circle, the whole group discusses the following questions.

- Did we know how to motivate members to contribute factors? Were we fair and efficient in our analysis of the offers made by the different members?

- Have we come up with a good plan for developing our own factors as a group? Are there other elements we can develop?

- Considering the member contributions and the development of factors by the group, do we have enough of our own factors? Can we say, realistically, that we will be able to acquire those factors that are still missing in order to create the enterprise?

- 1See Razeto’s Solidarity Economy Roads, Chapter 3, for an analysis of the “economy of donations.” https://geo.coop/story/solidarity-economy-roads-chapter-3 [-MN]

- 2Timebanking would be another example. [-MN]

- 3Members of workers collectives in Japan call this “tomoiku” 共育 or mutual education; it is a key element of the process they use to develop new collectives. [-MN]

- 4The solidarity group may want to revise the information requested to suit its context and needs. [-MN]

- 5It might be wise to have a “vibe checker” who can keep an eye on how people are feeling and intervene if necessary to address personal conflicts. - MN

Citations

Luis Razeto Migliaro (2020). How to Create a Solidarity Enterprise: Unit IV. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/articles/how-create-solidarity-enterprise-unit-iv

Comments

Addison

October 6, 2020, 4:39 am

These translations can't come fast enough. Thank you so much for sharing. I really appreciate Migliaro's approach.

In reply to These translations can't… by Addison

Josh Davis

October 15, 2020, 6:36 pm

We just posted the next unit: https://geo.coop/articles/how-create-solidarity-enterprise-unit-v

Add new comment