by Ethan Miller

Previous: Part Two: "The Name of the Trap Is 'The Economy'"...

From Economy to Livelihood: Five Principles

The glimmers of a new economic story are emerging. These are concepts and intuitions that can help to free our imaginations from the grip of the old "economy" and to embark on new collective explorations of how we might live together in this coming age of uncertainty and change. Let's start with five principles for re-orienting our economic thinking that can help us to move: (1) from a singular notion of "the economy" to a notion of diverse forms of livelihood; (2) from an economy/nature divide to a restorative concept of ecological community; (3) from a stale choice between "the market" and "the state" to a creative political space within and beyond these institutions; (4) from the limiting logics of "economic laws" to the work of creating new possibilities through collective imagination and action; and, finally, (5) from the economics of the "experts" to economics as a practice of democratic organizing in which "we the people" make our own economies.

Principle 1. From "The Economy" to Diverse Livelihoods

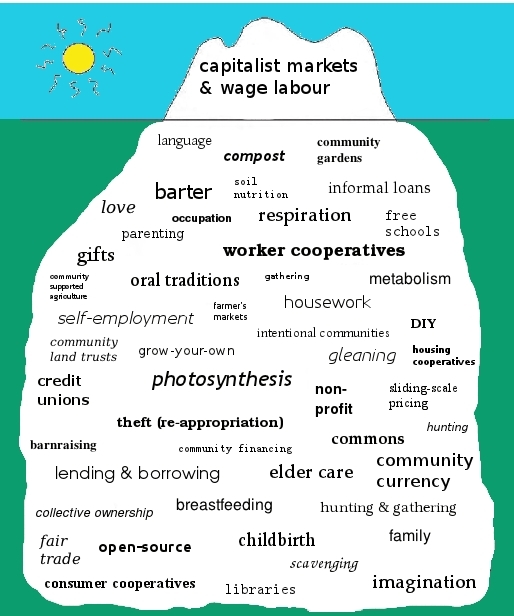

There is no single "economy," except as a story that is enforced by institutions to maintain the status quo. There are, instead, diverse forms of livelihood, multiple ways that we make our livings in relation to each other and to the living world of which we are a part.

The idea of a single "economic system" made of money and markets is a bankrupt story that serves only to make our economic possibilities invisible. In the real world-outside of the textbooks and the institutions who model the world on their ideas-we meet our needs through all kinds of different practices and relationships. It is time to move from a notion of "economy" to one of livelihood. This is not, any longer, about what the capitalist market demands of us. This is about how we make our living. How we make our lives.i

We are not just rational self-interest maximizers. We cooperate, we share, we identify with each other and create communities of care and support. Far from living in a world of cold business transactions, most of us live in worlds that are full of complex relationships, obligations, commitments, and forms of love. We fight tooth and nail to hold onto these spaces-the roots of our dignity-in the face of an economy that tries to rob them from us.

We do not just depend on jobs and money for our livelihoods. Our lives are more than our work, and our work is more than our jobs. We depend on each other, on our families and friends, on our neighbors and on the many communities of which we are a part. We depend on gift-giving and bartering, generosity and solidarity, lending and borrowing, sharing and holding resources in common. We depend on our own skills and the skills of others, on shared wisdom, and on shared forms of work within and beyond the workplace. These are the forms of livelihood, in fact, that keep us alive in the most difficult times. We don't rely on "the market" to provide us with our needs when the floodwaters rise, when the mill closes down, when the company downsizes, or when the hurricane strikes. We rely on each other, because we are the economy of life and community.

In a larger sense, we also rely on the ongoing labor of other living beings and the world itself, processes of livelihood which "the economy" cannot provide (and most often works to exploit or destroy): the plants that make our oxygen, the soils that grow our food, the insects that pollinate our fruit, the climate that turns our seasons, the clouds that bring the rain, and the wind that sweeps them away to reveal the sun. This is not "natural capital": this is our shared world. It cannot be turned into money.

Neither money nor "economic growth" are the sole measures of our well-being. Even as we struggle and strive to earn it, we do not all believe in the idea that money actually measures "value." We have other values, too: our health, our time to rest, play and to be free, our creative expressions, our spiritual and religious lives, our family commitments, our relations with the more-than-human living world, our traditions and our stories, and the possibility of a future for those yet to come. These values do not die, no matter how many times the economists ignore them and the insurance companies try to quantify them for profit: they make us who we are, we live them, and we pass them on.ii

The story of "the economy" has hidden from us our possibilities. These are not just imagined, not just fantasies of what might yet be. No: the creative action of generations of economic pioneers has already given rise to a whole array of living possibilities in which we might participate, or on which we might come to depend: worker, consumer and producer cooperatives; community currencies; fair trade initiatives; housing cooperatives and intentional communities; volunteer rescue and fire squads; collective childcare and education networks; community-run social centers; public libraries; non-profit community development credit unions; free schools; cooperative forms of no-interest financing; community gardens; neighborhood care networks; open source free software projects; community supported agriculture (CSA) programs; farmer's markets; community land trusts- commons of all sizes and shapes.iii

These are not utopian projects. They are the imperfect shapes of our creative struggles to build different forms of livelihood in this actual world. They call us toward possibilities that we have only begun to explore and to fight for.

Next: Part Four: "From Economy/Nature to a Community of Life" (principle #2)...

- 8.5 x 11 size (this one prints out nicely on letter-sized paper)

- Booklet-size (this one is easy to read on a computer screen)

- Ready-to-fold 'zine version (you can print this version and distribute it in your community or at your #occupation!)

i For more on this shift in perspective from a monolithic "economy" to a diverse landscape of practices, see J.K. Gibson-Graham, A Postcapitalist Politics. University of Minnesota Press, 2006; and Jenny Cameron and J.K. Gibson-Graham, "Feminising the Economy: Metaphors, Strategies, Politics." Gender, Place and Culture, Vol. 10, No.2, p.145-157; also other work of the Community Economies Collective.

ii Massimo De Angelis offers a powerful framework for thinking about values and "value struggles" in his book The Beginning of History: Value Struggles and Global Capital (London: Pluto Press, 2007). He draws on David Graeber's concept of "value as the importance of action" in David Graeber, Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

iii To put a few numbers into the mix: A recent study by the USDA shows that 29,000 cooperative businesses in the U.S. employ more than 2 million people. This includes over 200 worker-owned cooperatives and 26,844 consumer-owned cooperatives (many of which are credit unions-- non-profit alternatives to corporate banks). These are all businesses "mutually owned and democratically controlled by members who benefit from its products and services." Additionally, there are more than 250 community land trusts-cooperatively owed and democratically controlled parcels of land to support affordable housing and other projects-in the U.S. (National Community Land Trust Network), and hundreds of local currencies and barter networks of all kinds (see Community Currency Magazine's directory for just a few of these). The Data Commons Project is working to develop a more comprehensive directory of alternative economy initiatives of all kinds. The in-progress prototype can be found at: www.find.coop

iv The"iceberg" image is derived from an original by Ken Byrne, published in J.K. Gibson-Graham, A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Gratitude to Kate Boverman, who inspired this piece and provided crucial ideas and support, and to Michael Johnson, Annie McShiras, Cheyenna Weber, Len Krimerman and Anne O'Brien for their excellent thoughts and edits.

Ethan Miller is an activist, educator and researcher working to cultivate and support movements for solidarity-based economic transformation. He works with Grassroots Economic Organizing and the Community Economies Collective, and has lived for the past ten years at the JED Collective and Giant's Belly Farm in Greene, Maine. Ethan is currently on a hiatus in Australia, working on a PhD at the University of Western Sydney with the Community Economies Research Group.

Email Ethan at: leaving.omelas (-at-) gmail.com

Add new comment