[Editor's note: This is an excerpt from Elayne Archer's recently released memoir of living in a commune in Park Slope, Brooklyn from the early 70s to the mid 80s. You can order the book through your local bookstore, or purchase it online.]

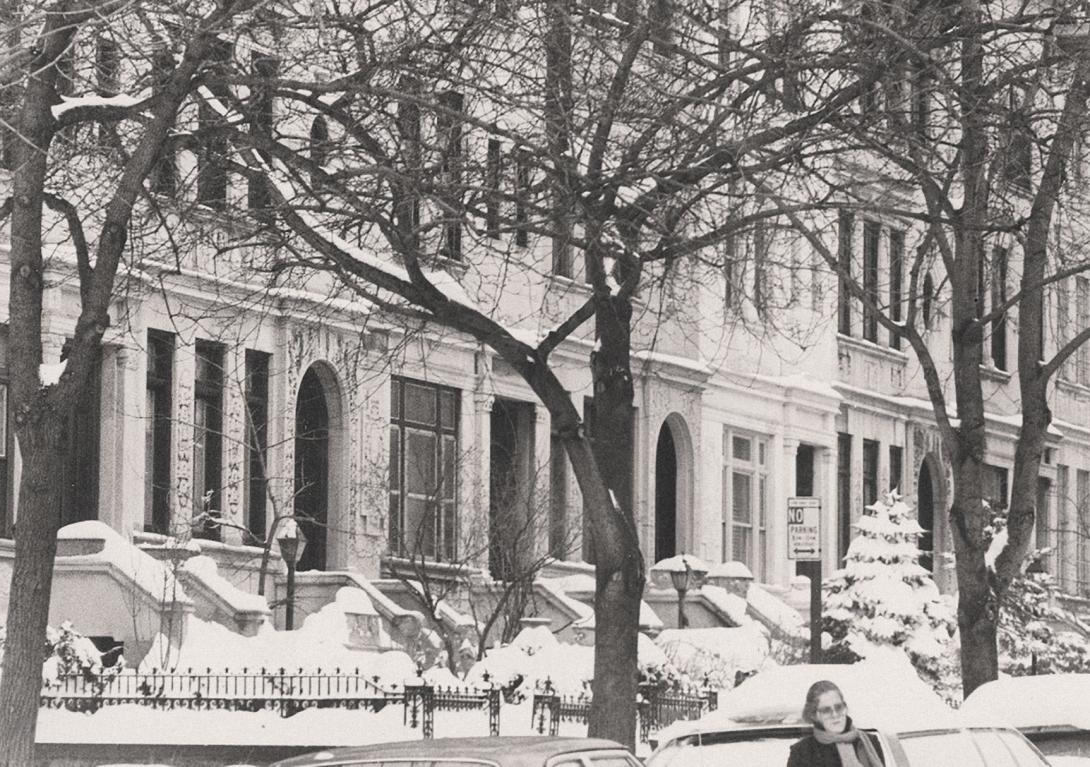

One cold, rainy, late fall day—December 1, 1972—three families (six adults and five children, aged 2 to 10) moved into a house in Park Slope, Brooklyn to set up a commune. The house was a two-family, four-story house, with two similar apartments, each with six rooms. As a commune, we would share the downstairs space and have nine rooms as bedrooms and studies for parents and children. We lived together as one family for almost fourteen years.

This was an urban commune—we did not raise chickens, we did not grow our own food, and we were not going back to the land. We shared childcare, housework, and cooking. We did not share income, we did not do drugs, and we did not read Mao and Che together. And most importantly, we did not share sex. But we did share expenses: each couple paid $500 a month, which covered mortgage, taxes, insurance, utilities, food, and, of course, childcare. This was not a small amount of money at the time but it was quite reasonable, given all that it covered.

The major need that the commune sought to address was childcare. At this time, there was little in the way of affordable childcare (kindergarten was half-day, and PreK was decades in the future.) We wanted to provide children with working mothers a safe and supportive environment in which to grow and flourish.

But it was not just the need for childcare that motivated us. We had what one grown commune child called a “communal mindset.” We believed that children would benefit from having siblings and from being raised by people other than their parents. We also believed that married life with young children took its toll on relationships, and that if couples could be freed from some of the burdens of childcare and household chores, their relationships would flourish.

The title of this memoir comes from an incident that occurred early one morning in the first year of the commune. One of my communal sisters, Suzanne, was rushing off to work. Her son, Robbie, was upstairs with his older sister. Just as Suzanne was about to leave, Robbie appeared on the landing somewhat disheveled—his shirt was unbuttoned, his belt unbuckled, and his shoes untied (no Velcro in those days). Suzanne hesitated. But Robbie, instead of looking to her, asked, “Who’s on today?” I was. I told Suzanne to leave, and I got Robbie dressed, breakfasted, and ready for the day. This is one example of how the commune worked.

There are few words are as loaded as the word “commune.” People think of communes as unstructured houses, often rural, with adults, often “hippies,” lying around doing drugs or out making the revolution, while children wander around unattended and partially unclothed. One communal child told me that whenever she told someone later in life that she had lived in a commune, the comments usually were: “Oh, you had a very unstructured childhood.” In fact, her childhood was quite structured—more structured than it might have been had her family lived alone in their Manhattan apartment.

The Commune Day

The heart of the commune was the schedule, and the biggest challenge we faced was making the schedule each semester. We had schedules for childcare, for cooking, and for housework. A typical day on in the commune was hard work. It meant taking care of the children for the entire day: making a full breakfast; taking the children to school (if another adult did not do this on the way to work); picking them up for lunch and at the end of the day; cooking dinner for the whole family; and doing the cleanup afterwards.

The commune day was hard work for the person on but the payoff was huge: you did it only once a week. On the other days, you could have breakfast with your child and leave for work without too much hassle. You did not have to wake your child early, as many parents must do today to get them to a childcare center in order to get to work on time. You left your child, knowing he/she was in good hands.

The schedule also meant that you did not have to rush home, buy food on the way, and throw together a dinner. On the contrary, you entered the house after a day at work to the wonderful smell of dinner cooking. Often, the children were relaxed—they had done their homework with the help of other children or the parent on and they didn’t run to you with demands for help as soon as you came in the door.

Christmas in the Commune: Just Like in the Movies

There were many celebrations in the commune: Thanksgiving, Hanukkah, Christmas, Easter, birthdays, and block parties. Most of these celebrations included a large meal, to which many friends were invited, as well as activities like playing the dreidel game, lighting the menorah, decorating the Christmas tree, playing charades, and dying Easter eggs.

One of my favorite commune memories occurred one Christmas Eve. Several commune members had gone to a carol service in the neighborhood and some of the children were playing in the basement. The group in the living room included me, my husband, my son, Matty, and one of the commune children, Joanna. We had just made Christmas cookies and were watching a Christmas special. It was a beautiful scene, especially with the tall Christmas tree shining bright with many lights.

At one point, Joanna looked around at all of us and said, “This is just like in the movies: It’s Christmas Eve, and the big sister and little brother are watching television with the mommy and daddy.” Then she paused and continued, “Of course, Matty isn’t really my brother, and Lainey isn’t my mother, and Neil isn’t my daddy. But apart from that, it’s just like in the movies.” And that’s what it was––just like in the movies.

The Commune’s Lasting Impact

Today, I am in touch with most members of the commune, especially the five children, as well as my communal sisters. I am also close to and babysat several of the communal grandchildren. In addition, my daughter Diana, who was not yet five when the commune broke up, has spoken of how the commune gave her a larger family. She is especially close to Joanna, who often takes care of Diana’s daughter, our granddaughter. The commune has been an extended family for my husband and me, which is a source of great comfort since we both come from small families.

Two commune children described the lasting impact of the commune. Leo describes his pride a having been raised in a commune.

Growing up in the commune created a bedrock view of the efficiency of the arrangement and the knowledge that I could always live communally again if I wanted to. I’m sure that there will be much more of this living arrangement among my daughters’ generation, and I think that’s a good thing. And I’m proud to have been part of a 1970s-1980s communal household.

In an essay written during his first year of high school, my son described the commune’s impact on the person he is today. It is a fitting conclusion to this memoir.

When I first moved into what I came to understand was a “commune,” I wondered what it was. It didn’t take me long to realize that I would be living with other families and other children. Adjusting to this was something that I had never experienced. I had to share all my toys, books, and sometimes clothes with people who had suddenly appeared one day. I had never had to share a bathroom, a bunkbed, or a kitchen before. I could barely grasp these concepts, but eventually I came out of my state of seclusion and opened up to these strangers.

I began to see the advantages as clearly as a three-year-old could. Christmas presents would be more abundant, and I would always have a playmate. As I grew older, I found it very enjoyable to live in a situation such as this. Whenever a commune parent asked me to do something, I felt greatly respected that they could trust me to do something for them. It was not like a chore but more of an honor that I could perform something for a non-relative as I could for my parents.

The disadvantages to this environment as I have found so far are only in regard to privacy. But this aspect is unimportant if you consider that these “strangers” are not at all that, but family. I think that twelve years in the commune have made me a more sharing, giving, and respectful person and that this experience will stay with me for a lifetime.

Who’s On Today: Life in a Brooklyn Commune can be ordered from Amazon or by taking the information to your local bookstore, which can order it from Ingraham, the national distributor.

Citations

Elayne Archer (2022). Who’s On Today: Life in a Brooklyn Commune. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/articles/whos-today-life-brooklyn-commune

Add new comment