Can Cooperative Land Ownership Enable Transformative Climate Adaptation for Manufactured Housing Communities?

[Editor's note: This article was first published in Housing Policy Debate, in February of this year. See the original for references. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND License.]

ABSTRACT

Residents of manufactured housing communities (MHCs) are disproportionately vulnerable to both hazards and displacement. The cooperative ownership model of resident-owned communities (ROCs) pioneered by ROC USA helps MHC residents resist displacement, but little research assesses how cooperative tenure impacts hazard vulnerability. To fill this gap, we conduct a spatial analysis of 234 ROC USA sites; analyze the co-op conversion process; and interview ROC USA staff, technical assistance providers, and resident co-op leaders. Although ROC USA communities, like other MHCs, face elevated exposure and sensitivity to hazards, we find that ROC USA’s model supports communities’ adaptive capacity by increasing access to financial resources, bridging formal and informal knowledge and skills, and improving social and institutional capacity. This networked cooperative model represents a scalable form of transformative adaptation by enabling low-income communities to address the underlying causes of uneven hazard vulnerabilities that are intensifying under climate change. We close with public policy and programmatic recommendations to enhance and expand this model.

We assess how cooperative land ownership and democratic self-governance impact the ability of residents of low-income manufactured housing communities (MHCs) to adapt to hazards, including those associated with climate change. Manufactured housing1 is the largest source of unsubsidized affordable housing in the United States (Durst & Sullivan, 2019), with 22 million residents in 8.5 million units (Freddie Mac Multifamily, 2019). Many residents face a dual burden of vulnerability to hazards and housing insecurity (Rumbach, Sullivan, & Makarewicz, 2020; Sullivan, 2018a). For instance, the land-lease model common in MHCs leaves residents open to lot rent increases and evictions that can cost them their homes, which are essentially immovable assets, despite being called mobile homes. Homes in MHCs are also often less disaster resilient than site-built housing because many were built prior to federal standards instituted in the 1970s, are sited in hazard-prone areas, or have vulnerable infrastructure systems.

Resident ownership of MHCs has become a growing alternative to private investor ownership and mitigates housing insecurity in the face of market speculation. As of 2019, there are 1,065 resident-owned communities (ROCs), constituting 2.3% of the approximately 45,600 MHCs nationwide (Freddie Mac Multifamily, 2019). ROCs help protect residents from eviction and result in lower rent increases compared with investor-owned MHCs (French, Giraud, & Ward, 2008; Ward, French, & Giraud, 2006), but there has been no systematic assessment of how resident ownership might impact hazard vulnerability and adaptation.

We therefore ask the question: How does collective land ownership and shared governance enable or inhibit adaptation to hazards among residents of MHCs? We focus on Resident Owned Communities USA (ROC USA), a nonprofit organization that has helped more than 250 communities cooperatively buy the land beneath their mobile homes. The ROC USA model, which incorporates elements of both traditional limited-equity cooperatives and community land trusts, has expanded rapidly over the last decade, creating the largest network of cooperatively owned MHCs nationwide. We assess how the model impacts hazard resilience by analyzing geospatial data on climate and socioeconomic vulnerabilities, documents on the co-op conversion process, and interviews with ROC USA staff, technical assistance providers, and co-op leaders.

Like MHCs in general, we find that ROC USA co-ops face heightened exposure and sensitivity to hazards because of peripheral and hazard-prone siting, the physical characteristics of their housing and infrastructure (which often reflect disinvestment under profit-oriented owners), and the demographic and socioeconomic disadvantages of residents. ROC USA helps communities reduce their vulnerability by: (a) improving access to resources such as low-cost loans and grants for capital improvements; (b) building capacity to assess infrastructure risks and leverage residents’ skills to make improvements; and (c) building institutional and social capacity to self-govern and self-manage. These findings suggest that networked, cooperatively owned MHCs, like ROC USA communities, are a promising model for people-centered housing resilience (Vale, Shamsuddin, Gray, & Bertumen, 2014).2 We argue this model provides a concrete case of “transformation” in the face of climate change (Pelling, 2011) by remaking the structure of residents’ relationship to land from precarious individual tenancy to cooperative ownership, which provides residents with the resources, incentive, and authority to adapt to hazard risks. ROC USA then melds internal community capacity with expanded access to external resources to help residents address risks and vulnerabilities.

Although this model helps low-income communities reduce environmental vulnerability, it has yet to systematically account for climate impacts through its recruitment, investment, and capacity-building strategies. Moreover, we find that in some cases, co-op ownership and governance can inhibit adaptation by reducing access to some forms of conventional financing and subjecting adaptation decisions to lengthy community processes, which can be marked by internal conflict and distrust. We close by offering recommendations for policy changes to help housing cooperatives like those created by ROC USA realize the potential of resident ownership in advancing transformative climate adaptation.

Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity in MHCs

Like residents of many forms of low-income housing, MHC residents are vulnerable to both environmental hazards and tenure insecurity. Low-income households and other marginalized groups are more vulnerable to environmental stresses, including toxic pollution (Pellow, 2007), natural hazards (Blaikie, Cannon, Davis, & Wisner, 2014), and uneven access to green amenities (Wolch, Byrne, & Newell, 2014). Climate change exacerbates these trends by making extreme weather events more acute or frequent (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2018), and worsening indirect stressors such as vector-borne disease (Parham et al., 2015), housing cost fluctuation (Bernstein, Gustafson, & Lewis, 2019; Indaco, Ortega, & Taşpınar, 2019), and infrastructure or utility costs (Diaz & Yeh, 2014; Hughes, Chinowsky, & Strzepek, 2010). However, only recently has research considered how poor Americans are impacted by climate change through heat stress in formerly redlined neighborhoods or exposure to hurricanes and floods in public or manufactured housing (Hernández et al., 2018; Hoffman, Shandas, & Pendleton, 2020; Pierce, Gabbe, & Gonzalez, 2018; Rumbach et al., 2020). Even less research has studied what helps disadvantaged groups adapt. For instance, we are not aware of research in the United States exploring the relationship between collective property rights and climate vulnerability in MHCs or other low-income communities.

MHCs are doubly vulnerable because of threats from displacement and hazards. Vulnerability to hazards is frequently described as a function of hazard exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2018). Exposure encompasses the probability of hazard events like hurricanes or heat waves impacting a place. Sensitivity depends on both physical conditions in the built environment (e.g., housing and infrastructure) and social characteristics of individuals, households, or communities (e.g., age, poverty, and citizenship status). Adaptive capacity is the ability of individuals or groups to anticipate, respond, and adapt to hazard exposure and sensitivity. Taken together, vulnerability reflects historical developments, societal structures, and decision-making processes that have shaped present-day hazard probabilities, sensitivities, and adaptive capacity (Wisner, Blaikie, Cannon, & Davis, 2004). Understood broadly, resilience encompasses not only the absence of hazard risks, but broader conditions of social well-being that enable communities to overcome past marginalization and thrive (Shi, 2020). The following sections characterize the vulnerability of MHCs along these dimensions.

Exposure

Regulatory exclusion, social stigma, and economic forces relegate MHCs to more environmentally exposed places. Around 46% of units are in metropolitan areas3 (Durst & Sullivan, 2019), where zoning practices ban them or restrict them to peripheral and nonresidential zones (Dawkins & Koebel, 2009; Mays, 1961) because many nonmanufactured housing residents and city decision-makers believe manufactured housing lowers surrounding home values (Beamish, Goss, Atiles, & Kim, 2001; MacTavish, 2007). De jure or de facto exclusion of manufactured housing from upper-class communities (Geisler & Mitsuda, 1987) means MHCs are more likely to be in commercial and industrial zones (Pierce et al., 2018; Sanders, 1986), poorer neighborhoods or municipalities (MacTavish, 2007; Pierce et al., 2018; Shen, 2005), and flood-prone sites (Baker, Hamshaw, & Hamshaw, 2014; Pierce et al., 2018). For instance, 32% of Vermont’s MHCs have land in a flood zone (Baker et al., 2014).

Sensitivity

Manufactured housing residents tend to be more sensitive to hazards because of socioeconomic characteristics (Cutter, Boruff, & Shirley, 2003), physical characteristics of housing and community infrastructure (Salamon & MacTavish, 2017; Simmons & Sutter, 2008; Wilson, 2012), and reduced access to jobs, shopping, hospitals, and schools (Pierce et al., 2018; Shen, 2005). Many MHCs in disaster-prone regions also lack evacuation planning (Chaney & Weaver, 2010; Kusenbach, Simms, & Tobin, 2009). Their affordability (on average, half the per-square-foot cost of site-built single-family homes) places homeownership within reach of poorer households (Durst & Sullivan, 2019; Rumbach et al., 2020). Median household income for manufactured housing residents is less than $35,000, compared with over $60,000 for all households nationally (American Housing Survey [AHS], 2019). They have median assets valued at $45,000 compared with $213,000 for households in site-built homes (CFPB, 2014). Compared with residents of site-built homes, MHC households tend to be older (32% headed by a retiree vs. 24%), more likely to have members with a disability (33% vs. 20%), and less educated (33% have a degree beyond high school vs. 67%; AHS, 2019; CFPB, 2014). Latinx, Native Americans, and recent immigrants, all of whom may be affected by other historical and ongoing forces of oppression or insecurity, represent a larger proportion of manufactured housing residents compared with residents of site-built homes (AHS, 2019; CFPB, 2014; Hart, Rhodes, & Morgan, 2002; Schmitz, 2004). Shared class, political and demographic characteristics, and stigmatization once offered a basis for solidarity among residents (MacTavish & Salamon, 2001). However, diversification of MHC residents can lead to wariness of dissimilar others that—along with fear of crime and poor park management—can undermine community relationships (McCarty, 2013).

Physical and infrastructural conditions also render manufactured housing units and communities more sensitive to natural hazards. Older units are especially sensitive to environmental shocks like wind, fire, and heat waves because there was no common standard for structural integrity, energy efficiency, fire safety, or material quality in manufactured housing prior to the adoption of national codes developed by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in 1976 (Grosskopf, 2005; MHI, 2020; Pearson, Longinow, & Meinheit, 1996; Simmons & Sutter, 2008; Wallis, 1991; Wilson, 2012). Many MHCs were founded as campgrounds or semiformal trailer camps during post-World War II housing shortages. Accordingly, many operate their own infrastructure systems, including water, sewer, roads, and electricity systems, that were cheaply built and are especially sensitive to disruption from environmental hazards and stresses (Wallis, 1991). Where owners resist making repairs and infrastructure fails (because of natural hazards or other causes), local governments often close MHCs in pursuance of safety regulations (Baker, Hamshaw, & Beach, 2011).

Adaptive Capacity

The ability to adjust and respond to hazard exposure and sensitivity is frequently discussed in terms of adaptive capacity. McEvoy, Mitchell, and Trundle (2020) frame adaptive capacity as a composite of three related elements: mobilizable resources, institutional and social capacity, and information and skills.

Lending policies inhibit residents from mobilizing resources for household upgrades. For legal purposes, most states consider manufactured housing to be personal property (chattel), not real estate. This means that compared with site-built homes, owners receive shorter loan terms (often 10 or 20 years), have fewer lenders to choose from, and pay higher interest rates (30-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgages Since 1971, 2021; NCLC & Prosperity Now, 2010). Lenders are not required to provide foreclosure warnings to manufactured housing residents, who also are often not eligible for federal or state disaster aid. For instance, the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act protected mortgage holders—but not chattel loan holders—from losing their home because of the pandemic (Bourke & Siegel, 2020).

The ownership structure of conventional MHCs gives residents little agency to shape community governance or build social and institutional capacity. Typically, a private owner or investor owns the land, infrastructure, and communal facilities such as community buildings and playgrounds, whereas residents own or rent their unit and pay monthly lot fees. This halfway homeownership (Sullivan, 2014) or land-lease tenure model, which applies to approximately 40% of all manufactured housing units nationwide (Durst & Sullivan, 2019), creates a power imbalance between owners and residents that is ripe for exploitation (Ehrenfeucht, 2018; Genz, 2001; NCLC & Prosperity Now, 2021). It is often not feasible to move mobile homes—despite the name—because of their structural weaknesses, the high cost of relocation, and shortages of available lots (Freddie Mac Multifamily, 2019; MacTavish, Eley, & Salamon, 2006; Salamon & MacTavish, 2017). Residents have little recourse when park owners defer maintenance, raise lot fees, or close or redevelop communities (Desmond, 2016; Formanack, 2018). MHCs have become targets of acquisition by big investors (Freddie Mac Multifamily, 2019) precisely because the standard model provides MHC owners significant freedom to maximize profits. The two largest owners of MHCs nationwide are publicly traded real estate investment trusts and large privately held operators, which have rapidly consolidated MHC ownership (Petosa, Bertino, Edwards, & Herskowitz, 2020).

Lack of access to information regarding the for-sale status of properties limits residents’ ability to organize to prevent evictions or rent increases under new ownership. Twenty states require owners to notify residents of potential sales, give tenants an opportunity to purchase their community, or provide tax incentives for resident purchases (NCLC & Prosperity Now, 2021). The presence or absence of such protections is a major determinant of whether residents can effectively organize to resist displacement, including by purchasing their own community (NCLC & Prosperity Now, 2021). Where residents can purchase their community, aging infrastructure can add considerable costs and complications. Investor-owners have little incentive to repair infrastructure, leading to ballooning costs to redress code violations, unsafe conditions, and infrastructure failures (Ehrenfeucht, 2018; Rogers, 2020).

Cooperative Responses to Vulnerable Housing

In the United States, housing activists and scholars have advocated for shared-equity housing models, including limited-equity cooperatives (Saegert & Benítez, 2005), community land trusts (Davis, 2010; DeFilippis et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2020), and ROCs) (Ward et al., 2006) as promising ways to create and preserve affordable housing (Ehlenz & Taylor, 2019). A limited-equity cooperative owns land and housing (often a multifamily apartment building), and residents own a limited-equity share in the cooperative (e.g., through a membership fee; Ehlenz, 2018). Community land trusts are mission-driven nonprofits that own the land while individuals own or rent housing units. Both models typically restrict resale values, eligible buyer income, or both to maintain affordability. Research finds that cooperative property rights can slow gentrification, strengthen community stability and wealth creation, and build capacity to respond to market pressure (Choi, Zandt, & Matarrita-Cascante, 2018; Sazama & Willcox, 1995).

However, cooperative models have been difficult to scale up given land costs, lack of public subsidies, and reliance on volunteers for governance (Moore & McKee, 2012). Reflecting community land trusts’ slow growth, there remain fewer than 40,000 units of rental and homeownership housing in around 225 such trusts in the United States (Grounded Solutions Network, n.d.). Cooperative land tenure and housing schemes require multiscalar policies to support their establishment and continued functioning, and inadequate support can hinder their ability to flourish or grow (Ganapati, 2010). Moreover, cooperative ownership introduces new challenges, starting with defining who belongs to a community, who has decision-making power, and who benefits from investments and increasing property values (Bossuyt, 2021; Vidal, 2019; Vogel, Lind, & Lundqvist, 2016).

ROC USA responds to some of these challenges in the context of MHCs. It began as a program of the New Hampshire Community Loan Fund (NHCLF) in the 1980s, then became an independent nonprofit in 2008. It offers technical assistance for ROCs through a network of nine affiliated certified technical assistance providers that identify interested communities and guide them through the resident purchase process. ROC USA also operates a financing arm, ROC Capital, that provides low-cost debt financing for acquisitions, refinance, and capital improvements. Typically, residents seeking to buy their MHC establish a cooperative and take out a loan from ROC Capital or another lender for the cost of acquisition and initial capital improvements. Residents continue to own their units individually but buy a membership interest in the cooperative ($100 to $1,000 per household). The low share price reduces barriers to entry so that all residents can gain an equity stake in the cooperative and participate in community decision-making. However, the low share price also means that cooperatives take on heavier debt burdens, with loan-to-value ratios of up to 110%, to cover closing costs and capital improvements. This model requires mission-driven financing through ROC Capital, other community development finance institutions, or publicly subsidized low-income housing financing. Funding for ongoing technical assistance and training is also built into acquisition loans to support cooperatives for at least their first 10 years of operations.

The ROC USA model allows residents to build equity in their homes while preserving affordability and stability through collective land ownership. The articles of incorporation for ROC USA cooperatives carry restrictions on the sale of a community’s land and infrastructure, requiring that profits of any sale be donated to affordable housing organizations in the relevant housing market. These restrictions remove the potential for windfall profits. To date, no ROC USA community has defaulted on its loans, sold its land, or reverted to private ownership. In most cases, ROC residents can sell their homes at fair market value. Common provisions in ROC bylaws state that low-income households on a community’s waiting list must be given priority access to purchase any homes for sale. Given that most ROCs do not impose price restrictions or buyer income restrictions on private home sales, the model largely relies on the “natural affordability” of manufactured housing to maintain affordability (Bradley interview). In some cases, specific sources of financing used for ROC acquisitions, especially state government affordable housing funds, do restrict sales of private homes by requiring ROCs to maintain a minimum proportion of low-income households. According to ROC USA’s internal data, 85% of households in reporting communities are low income (earning <80% of area median income, AMI) and 58% are very low income (<50% of AMI).

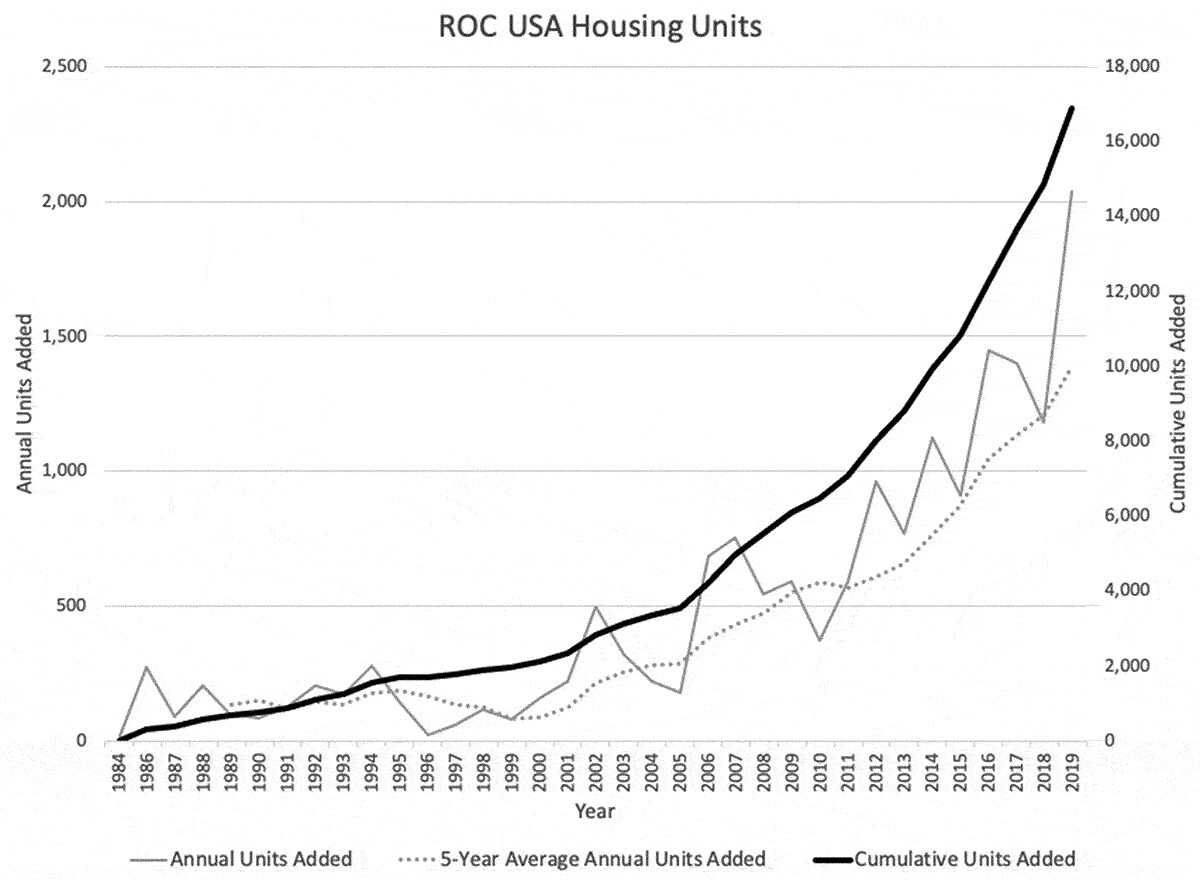

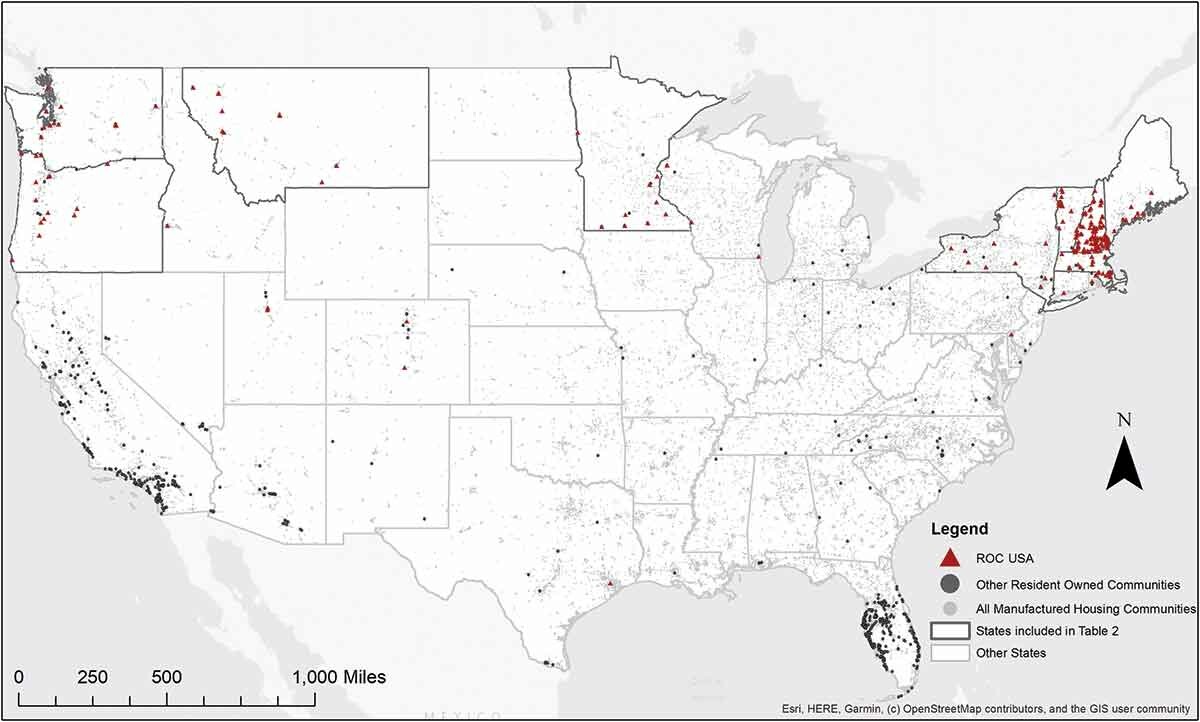

The ROC USA network is the largest affiliated group of ROCs nationwide and has spread quickly in recent years. By early 2020, the network included more than 250 resident-owned MHCs, home to almost 17,000 households (see Figure 1). ROC USA communities are most concentrated in New Hampshire (which represents 53% of all ROCs in the network) where the organization started and developed its model before diffusing nationally. ROC USA communities represent 45% of all MHCs in New Hampshire, a far higher percentage than in any other state (Department of Homeland Security, 2018; ROC USA, 2019).4 Other ROC USA co-ops are concentrated in the Northeast, Pacific Northwest, and Minnesota. By contrast, few are located in southern, Sunbelt, and western states, although these states have the highest number of MHCs overall (see Figure 2). Except for eight communities in Texas, Utah, and Wisconsin, all ROC USA co-ops are in states with at least basic legal protections for manufactured housing residents (NCLC & Prosperity Now, 2021). As of 2020, ROC USA communities collectively represent the country’s 12th largest holding of manufactured housing units (Petosa et al., 2020). Outside of ROC USA, 690 of the 1,065 ROCs nationwide are independent communities in Florida and California that are primarily market-rate co-ops, many of them age-restricted retirement communities (Freddie Mac Multifamily, 2019).

Figure 1. Growth of resident-owned communities (ROC) USA-affiliated cooperatives by year.

Figure 2. Map of manufactured housing communities nationwide, by type.

Despite this growth, few studies have examined ROC USA and other cooperative manufactured housing communities. When comparing resident and investor-owned communities in New Hampshire, researchers found ROC members had lower lot fees, higher resale values, and less time on the market, and were more likely to have a fixed-rate loan. Residents’ feelings of stability, ownership, and control were stronger in ROCs than in investor-owned properties (French et al., 2008; Ward et al., 2006). A profile of ROC USA’s technical assistance provider in Oregon describes similar benefits to residents and highlights the relatively low cost of preserving affordable manufactured housing compared with traditional new housing construction (Catto, 2017).

Other research has analyzed the formation and operations of other types of cooperatively owned MHCs, including farmworker housing cooperatives. In the context of California’s 1992 Polanco Bill that allowed the development of farmworker housing on land zoned for agriculture, groups collectively purchased land to form informal cooperatives, referred to as polancos. Although some California farmworker housing cooperatives have a fixed-equity community structure similar to the ROC USA model, the informal nature of these communities can lead to challenges, including the lack of an established, legally recognized shared-ownership structure; lower standards of initial property and infrastructure development, with potential safety repercussions; and little access to traditional financing options (Mukhija & Mason, 2015). Although fixed share prices for buying into the community aim to retain affordability, unrestricted pricing of the individually owned manufactured housing units has put this housing out of reach of many low-income farmworkers (Bandy & Weiner, 2002).

Past research sheds light on the struggles and benefits of resident ownership for low-income MHC residents, but no research has considered the way these models impact how residents confront environmental hazards. As MHC residents face mounting environmental and tenure security threats, the ROC USA network affords an opportunity to learn whether and how ROCs address hazard vulnerabilities and how state and nonstate actors might support them in the future.

Research Methods

We focus on the ROC USA network because, as a Freddie Mac report on ROCs notes, the limited-equity form of MHC is “nearly synonymous with [the] ROC USA organization” (Freddie Mac Multifamily, 2019, p. 2). Given the research gaps above and the absence of data on ROC USA communities, we adopted a mixed-methods approach.

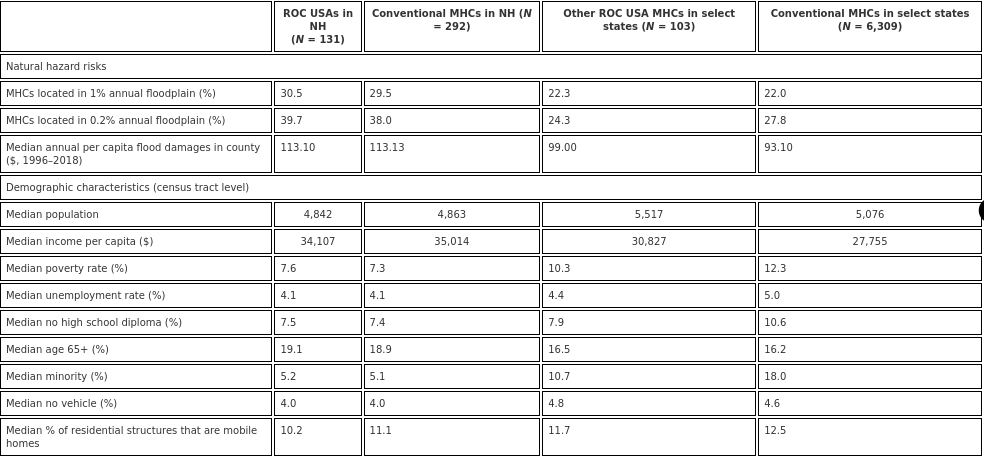

First, we used Geographical Information System (GIS) to map and characterize the 234 ROC USA-affiliated communities in nine states where the network had at least nine member communities (the median state presence) at the time of writing. We used data from ROC USA; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index; socioeconomic data from the 2018 U.S. Census; 100- and 500-year floodplains from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Flood Insurance Rate Maps; and the Spatial Hazard Events and Losses Database (SHELDUS). To measure comparative rates of hazard vulnerability, we compared the hazard risk and demographics of ROC USA communities with those of other MHCs in the same states. Table 1 summarizes these demographic, socioeconomic, and hazard exposure data. Because the concentration of ROC USA co-ops is higher in New Hampshire and because the state is generally less diverse and higher income than the other states in which ROCs are common, we disaggregate the New Hampshire data in Table 1.

Table 1. Natural hazard, socioeconomic, and demographic characteristics of resident-owned communities (ROC) USA and non-ROC USA MHC locations in nine states

Second, to better understand the policies and procedures guiding ROC USA formation and self-governance, we reviewed documents, including the extensive ROC USA Management Guide and a selection of reports on property conditions produced for MHCs as part of the due diligence process for co-op formation. We also observed two events: a meeting of the regional ROC USA Association and a ROC USA cooperative leadership training session. Restrictions on travel and in-person meeting because of the COVID-19 pandemic limited on-site fieldwork.

Third, we interviewed 27 people in 2020. Twenty-five were people in three categories of ROC USA stakeholders: ROC USA staff, including the organization’s founder and executive director, Paul Bradley (multiple interviews, n = 3); staff from each of the network’s 11 certified technical assistance providers (CTAPs, hereafter TA provider or just provider, some interviewed multiple times, n = 16); and resident leaders of co-op MHCs (n = 6) (see Table 2). The relatively modest number of resident interviews reflects the fact that field interviews were beyond the scope of this research phase, especially during COVID-19. Instead, we relied on TA providers and co-op leaders to describe the programmatic aspects of the ROC USA model and the diversity of contexts and issues they face. We also interviewed two TA providers who work with independent ROCs (not associated with ROC USA). The semistructured interviews used interview guides and ranged from 45 to 90 min. Nearly all interviews took place by phone or video conference, and were recorded and transcribed when permitted. Except for Paul Bradley, all interviews are anonymized to protect interviewees’ and communities’ identities. Interviews are cited as “CTAP interview,” “Co-op Leader interview,” etc.

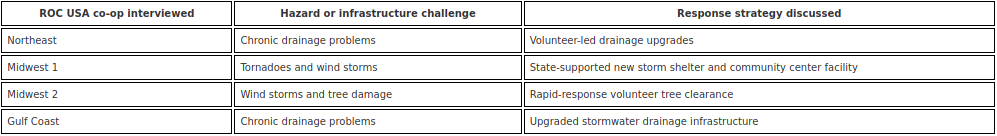

Table 2. Hazard-impacted ROC USA communities discussed in the article

Interview questions addressed the mechanics and challenges of converting conventional MHCs to ROCs, experiences of hazard impacts and infrastructure challenges, and processes used to support ongoing community governance and management. We sought examples of communities that had faced hazards and infrastructure challenges, including both those that had overcome challenges and those that continue to struggle. Following initial open coding to identify common themes and patterns, interviews were coded with particular attention to the three dimensions of adaptive capacity discussed above: resources, social and institutional capacity, and information and skills.

ROC USA Communities and Hazard Vulnerability

Natural Hazard Exposure of ROC USA Communities

All ROC USA communities began as conventional MHCs. Many, like MHCs generally, therefore face heightened exposure and sensitivity to hazards like windstorms, tornados, floods, wildfire, and drought.

shows that ROC USA communities are as likely as other MHCs to be in or within 1,000 feet of a 100- or 500-year floodplain. ROC USA communities are also similar to MHCs in general with respect to recent flood damage reported in their host counties, suggesting a lack of substantive selection effects (creaming) with respect to the role of hazards in shaping which MHCs convert to cooperative ownership using the ROC USA model (see Figure 3 and Figure 4 for examples). In interviews, TA providers and co-op leaders discussed direct impacts from and exposures to a range of hazards, including windstorms in New England, tornados in Minnesota, torrential rains on the Gulf Coast, and nearby wildfires in Oregon.

Figure 3. A resident-owned community in the mountain west. Photo Courtesy of ROC USA.

Figure 4. Residents of a resident-owned community in the upper Midwest. Photo Courtesy of ROC USA.

Changes in ROC USA policies may make resident ownership less accessible to hazard-exposed communities. Since 2008, ROC USA’s due diligence process has excluded communities with more than a trivial percentage of their property in the 100-year floodplain (Bradley and CTAP interviews). This floodplain exclusion reflects an effort to strengthen pre-acquisition due diligence to ensure that hazard vulnerabilities are accounted for and, in some cases, avoided. For example, residents in a Vermont MHC could not become a ROC USA co-op because inspectors found severe hillside erosion that required an expensive retaining wall (CTAP interview).

Sensitivity of ROC USA Residents to Natural Hazards

Like other MHCs, ROC USA co-ops face elevated hazard sensitivity because of both social and physical characteristics. Table 2 shows the demographic analysis of census tracts that are home to ROC USA communities, which are comparable with those that are home to other MHCs in the same states. Whereas studies find ROC USA co-ops have a higher resale value compared with traditional MHCs in New Hampshire (Ward et al., 2006), there are no substantive differences in socioeconomic and demographic characteristics between the state’s census tracts that host ROC USA communities and those that host all MHCs. In other states with significant numbers of ROC USA co-ops, ROC USA communities are situated in census tracts with somewhat lower racial diversity than traditional MHCs, slightly higher incomes and education attainment, and slightly lower poverty and unemployment rates. Without longitudinal MHC-level data, it is not possible to make robust causal claims about the role of cooperative ownership in shaping socioeconomic well-being. Nor has ROC USA systematically tracked this information. However, the broad similarities in the demographic characteristics between census tracts hosting ROC USA communities and those hosting other MHCs suggest shared patterns of sensitivity to hazards.

Interviews highlighted that ROC USA co-ops, like other MHCs, struggle with the hazard sensitivity of community-owned and operated infrastructure systems and older manufactured housing units. Although ROC USA does not keep systematic data on the age of homes, many ROC USA homes, like those in other MHCs, were built before the adoption of national manufactured housing building codes in 1976 and have lower construction standards. Aging infrastructure systems in ROCs are increasingly stressed by climate change-implicated hazards. Drinking water wells in ROC USA co-ops in Vermont and Oregon have run dry during droughts. ROC USA co-ops in New Hampshire and Texas have suffered persistent waterlogging when heavy rains overwhelm inadequate internal drainage facilities (CTAP and Co-op Leader interviews). The infrastructural sensitivity found in ROC USA co-ops is often a function of inherited infrastructures that were inadequately designed or poorly maintained under previous ownership regimes. However, interviews suggest that resident ownership, especially in the context of a well-supported network of cooperatives, can enable residents to take action to address these vulnerabilities.

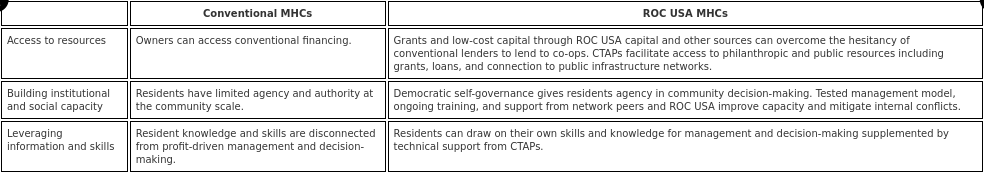

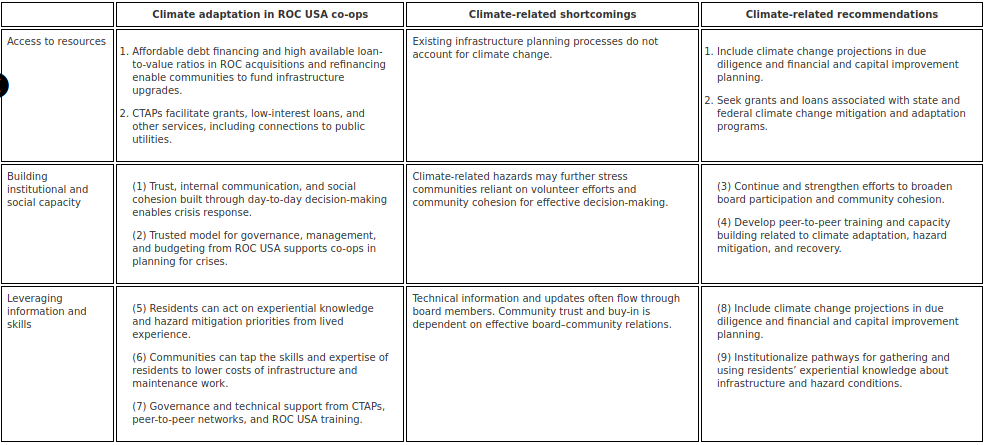

How the ROC USA Model Builds Community Adaptive Capacity

Although ROC USA communities share the hazard exposure and sensitivity of other MHCs, we find that cooperative ownership can increase communities’ adaptive capacity to reduce vulnerabilities. Building on McEvoy et al. (2020), we consider adaptive capacity to consist of three parts: (a) mobilizable resources, (b) institutional and social capacity, and (c) information and skills. The ROC USA model enhances the capacity of member communities in each of these areas by helping them obtain collective land ownership and leverage their collectivity for material and governance improvements. Table 3 summarizes these dimensions of adaptive capacity in conventional and ROC USA MHCs.

Table 3. Comparison of resident-owned communities (ROC) and conventional manufactured housing communities’ adaptive capacity

Access to Resources

Across U.S. affordable housing and community development sectors, networks of public, nonprofit, and philanthropic actors provide grants and subsidized loans to enable affordable housing acquisition, development, and operations. For most of these actors, MHCs are outside of their core areas of operation. Further, many such entities are not experienced in working with cooperatively owned and governed communities. As such, ROCs are doubly marginalized from conventional community development finance and grant-making processes. This marginalized status makes the work of ROC USA and their network of CTAPs all the more essential in facilitating co-op formation, ongoing operations, and hazard mitigation efforts. Facilitating access to low-cost debt financing for cooperative acquisitions, refinancing, and capital improvements is one of ROC USA’s central functions. With help from CTAPs and ROC USA, MHCs assemble necessary funds using commercial debt, grants and loans from public and philanthropic sources, and low-cost debt from ROC Capital, ROC USA’s affiliated community development finance institution. ROC USA’s record of zero defaults enables ROC USA to continue accessing low-cost capital from lenders who are often skeptical of cooperatives (Bradley interview). Loan-to-value ratios up to 110% allow new ROCs to make substantial investments in repairing and upgrading infrastructure as part of their acquisition financing. ROC USA acquisition loans are typically amortized over 30 years, but decadal renewals trigger reviews of community financial health and capital improvement needs.

Beyond initial acquisition financing, TA providers connect co-ops with additional resources through place-based networks. In one Midwest ROC USA co-op, much of the funding for a new tornado shelter and community center came from a state grant facilitated by their TA provider. A provider reported that residents of ROC USA co-ops are generally “folks of modest means” and the provider sees it as “our job as an organization to hunt down resources to help” with infrastructure challenges and other problems (CTAP interview). Similarly, interviewees associated with several ROC USA co-ops reported that TA providers helped connect their communities to public utilities to avoid ongoing costs and hazard vulnerability associated with independent infrastructure. A provider reported that one of their primary functions is to provide “good relationships with municipalities or other support organizations” (CTAP interview). Providers and ROC USA often act as “fiscal agents” for ROC USA communities, enabling co-ops, which are typically not incorporated as 501(c)(3) organizations, to receive public or private grants that would otherwise be unavailable to them (CTAP interview).

Building Institutional and Social Capacity

To supplement and build a community’s internal capacity, ROC USA’s network of TA providers serves as its “boots on the ground” throughout pre- and post-acquisition challenges (CTAP interview). During acquisitions, they help residents grapple with complex real estate transactions. Afterward, they help residents form and elect a co-op board whose responsibilities include insurance and bookkeeping, setting and collecting lot fees, budgeting, making decisions on maintenance and investments, and emergency preparedness. Many co-ops contract with external property management firms to handle some financial and management functions, whereas others rely extensively on resident volunteers for both management and physical work.

In addition to technical assistance support, ROC USA also provides regular national and regional training, including the annual ROC Leadership Institute, to build community capacity for management, leadership, and self-governance. Co-op leaders reported that peer-to-peer learning opportunities are among the most valuable parts of their affiliation with ROC USA. One co-op leader said that co-op residents and leaders are “much quicker to pay attention to a peer who lives…in that same [co-op] world” (Co-op Leader interview).

In addition to formal technical assistance and training, ROC USA also relies on informal strategies for building internal trust and solidarity. One TA provider reported that being “resident owned has helped communities to bond in a way that they weren’t” under conventional ownership (CTAP interview). Some co-ops‘ boards oversee social activities, such as block parties, food drives, and volunteer cleanups (CTAP interview). A provider in the Mountain West emphasized the importance of informal social activities in building trust between co-op boards and residents, saying,

Once the co-op is formed, there can be a bit of separation between the board members and the rest of the community…. The board needs to encourage the social and community side of things. They have rules and bylaws that need to be enforced, but it is also important to take the time and spend a little money to have a potluck or hold a holiday event [like] trick-or-treating. (CTAP interview)

According to interviews, this mutual trust and social cohesion enables co-ops to mobilize to address problems. A Gulf Coast ROC USA co-op provides a clear illustration of the importance of what one TA provider referred to as “group cohesion and group identity.” According to providers and co-op board members, the community, in which nearly all residents are Spanish-speaking immigrants, is marked by a strong sense of community cohesion and social trust. A board member expressed that their choice to invest in expensive drainage and energy efficient street lighting was rooted in their commitment to long-term community well-being, saying “these are our children,” “we can’t be thinking about short-term [solutions]” (paraphrase of co-op leader from CTAP interview).

Social solidarity among co-op residents is especially important in times of crisis. During the summer 2020 COVID-19 outbreaks, many co-ops reported robust mutual aid efforts. One TA provider reported seeing “members step up and try to connect with the community…grocery runs, social committees sewing masks” (CTAP interview). According to providers and co-op leaders, preexisting social networks and relationships were essential to facilitating these mutual aid efforts, even as most ROCs were forced to transition to remote communication and meetings (CTAP interviews).

Interviewees overwhelmingly regarded democratic decision-making as increasing the agency and problem-solving capacity of ROC USA residents. However, many acknowledged that the self-governance structure can also make management and decision-making more complex. Several interviewees commented on the slow and cumbersome nature of co-op governance. As one TA provider said, “democratic decision-making is slow and annoying and you don’t always get your way…by definition” (CTAP interview). In most communities, only a small subset of resident owners regularly participate in meetings and decision-making. One provider reported that “limited participation is a huge issue” (CTAP interview). Another said that “member engagement is a struggle across the board…. Every board wishes more people would step up” (CTAP interview). Resident ownership and self-governance can place a heavy burden on the subset of community members who take on active roles. A previous study of ROC USA communities labeled this uneven burden “differential commoning,” a phenomenon wherein certain community members bear disproportionate burdens of community care and maintenance (Noterman, 2016). A provider mentioned that smaller communities with fewer volunteers can face challenges with long-term leadership, saying “people who volunteer don’t want to do so indefinitely” (CTAP interview). One Midwest ROC USA co-op leader reported that they had been president of their co-op board for nine years and said that this came with a personal cost: “our mental health tends to fall by the wayside as community leaders doing this year after year” (Co-op interview).

The institutional and social capacity of co-ops can also be negatively impacted by internal division and conflict among residents. One provider reported, “If you have a park with a diverse population—it could be personal, political, linguistic, religious viewpoints—people might say ‘I’m not going to take that extra step to reach out to someone who speaks another language.’” They also described how long-standing conflicts and personal disputes can get in the way of effective community decision-making, saying, “people can now have old conflicts that come out in the management and board structure” (CTAP interview).

Although resident ownership can be an effective tool for creating institutional and social capacity in support of adaptive capacity, there are wide variations between communities. Democratic self-governance can enable co-ops to address complex challenges, but it can also be inefficient, ineffective, and prone to disruption by unrelated social conflicts. These challenges reinforce the importance of support from entities like ROC USA that can both enable external assistance (e.g., training and technical assistance) and build strategies to support internal social solidarity within and between co-ops (e.g., peer-to-peer networking).

Information and Skills

Recognizing and addressing climate and other hazard vulnerabilities requires accurate information about the risks and relevant skills to manage and coordinate risk mitigation and response measures. The structure of the ROC USA model enables network communities to access both formal technical information and informal experiential knowledge related to their infrastructure systems and hazard vulnerabilities. Before acquisition, ROC USA provides forgivable preacquisition loans for legal fees and engineering studies, such as environmental assessments and property conditions reports that assess infrastructure systems, identify deferred maintenance, and project capital improvement expenses for 10 years.

Although any buyer of an MHC would likely assess the state of a community’s infrastructure, the ROC USA process is supplemented by residents’ own experience. As part of the property conditions report study, every resident in a potential ROC USA community is asked to fill out an infrastructure survey detailing their experience of infrastructure functions and failures, including issues like nuisance flooding and interruptions in water, sewer, and electrical services (ROC USA Infrastructure Survey). ROC USA’s director reports that although other, nonresident MHC buyers could “hire the same engineers we would,” they “wouldn’t have the residents’ insights…people know where the bodies are buried” (Bradley interview). In the words of one TA provider, these reports and capital improvement plans provide communities with “a crystal ball to see into the future to anticipate any issues” with their infrastructure systems and environmental liabilities (CTAP interview). Having accurate projections for infrastructure expenses is especially important for co-ops because, unlike large investor owners, ROCs do not have large portfolios of assets against which they can borrow if they face unanticipated capital expenses.

Unlike off-site property managers or absentee owners, co-op residents who own, manage, and live in these communities can draw on experiential knowledge about their infrastructure and priorities. After years of suffering from regular ponding on roads, the predominantly Latinx co-op discussed above prioritized improving their drainage infrastructure once they gained ownership. With these investments in place, the community avoided the substantial flooding that beset neighboring areas during Hurricane Harvey. In another example, a TA provider reported that, for one upper Midwest ROC USA community, the need to improve their storm shelter was “part of the collective consciousness of the community because they had a devastating tornado [come] through in the 1990s” (CTAP interview). A board member in another upper Midwest ROC USA co-op noticed a downed tree blocking the entrance to a home after a storm early on a weekend morning. As resident owners, they did not have to wait for off-site property managers to call in outside contractors to fix the problem; they mobilized several co-op members with chainsaws to remove the tree within 15 min (Co-op Leader interview).

In age-restricted communities, retired residents often have skills and time to help manage co-op affairs. One provider reported that communities with many retirees benefit from having “people with a background in different fields, they step up to tackle infrastructure challenges” (CTAP interview). A co-op in the Northeast reported mobilizing their extensive resident volunteer capacity to install and maintain stormwater drainage infrastructure in response to chronic nuisance flooding (Co-op Leader interview).

Whereas residents of investor-owned MHCs likely have significant relevant information and skills that could be useful in informing infrastructure and hazard mitigation decisions in their communities, they lack the authority or incentive to put those skills and knowledge to work for their landlords. Resident owners in ROCs have a direct incentive to use their expertise to improve their communities and reduce capital and operations costs. Peer-to-peer support through ROC USA supplements each community’s internal skills and knowledge by linking it to a growing network of similar communities with ever-deepening problem solving expertise. Finally, ROC USA’s robust systems for due diligence and technical support further supplement community skills and knowledge with outside technical expertise where necessary.

Networked Cooperative MHCs as Sites of Transformative Adaptation

Despite the fact that the ROC USA model does not explicitly focus on climate change adaptation or hazard mitigation, but rather focuses on improving tenure security and self-governance for low-income MHC residents, the model clearly enables what Pelling calls “transformative adaptation.” The adaptation benefits that we observed in co-ops, however, are largely limited to the scale of an individual community. Nonetheless, becoming a cooperative represents a “radical change” “that shifts the balance of political and cultural power” (Pelling, 2011, p. 84). This approach addresses underlying structural causes of climate vulnerability and enables ongoing adaptation that is simultaneously community-driven and linked to broader state and nonstate institutions.

ROC USA’s model makes use of cooperative land ownership and networked governance and support to build community adaptive capacity. Reflecting findings from other research on cooperative land tenure, resident ownership offers MHC residents security from eviction and an incentive to apply their own knowledge and skills toward improving community resilience. Since ROC USA’s formation, no affiliated community has defaulted on a loan, returned to private ownership, or been redeveloped, displacing residents. The model still allows residents to build equity in their home in line with market dynamics. The sense of security, stake in the community, and decision-making power allows residents to prioritize household-level and community investments according to their own experiential knowledge and tolerance of risk. ROC USA co-ops rely on community self-governance, which empowers (and obligates) residents with relevant skills to contribute time and effort toward management, maintenance, organizing, and social cohesion. Experiences with effective self-governance can then build confidence and social capital in tackling larger-scale challenges, including public health crises and environmental disasters.

This strategy does not rely solely on the heroic self-sufficiency of low-income communities to solve their own problems. ROC USA co-ops rely extensively on outside support, including, most fundamentally, state legislation enabling cooperative purchase of MHCs; technical assistance from a network of regionally based providers; affordable financing from ROC Capital and elsewhere; and infrastructure assessments and capital improvement planning from ROC USA’s due diligence process. Although many efforts to promote the resilience of low-income and urban communities have been critiqued as advancing broader processes of state retrenchment and neoliberal privatization of risk (Davoudi, 2018), the ROC USA model does not represent an alternative to public sector infrastructure investment and hazard mitigation. Rather, cooperative ownership under the ROC USA model often enables more effective connections to public sector institutions and resources, including increasing access to public sector grants and loans and facilitating connections to public infrastructure networks.

Nevertheless, current ROC USA co-op formation, due diligence, and management processes do not explicitly address changing climate conditions. The robust due diligence process provides ROC USA-affiliated communities with safeguards to encourage them to build adequate reserve funds for infrastructure maintenance, repair, and replacement. However, ROC property conditions reports and capital improvement budgets are based on historical conditions and do not account for climate change. Moreover, safeguards are typically only in place during the first 10 years of each co-op’s loan. Unless a community refinances with ROC USA, technical assistance generally ends after 10 years and co-ops are free to adopt less rigorous standards for capital improvement planning, maintenance, and reserve funding, creating vulnerabilities to hazard events or infrastructure failures.

For many MHC residents facing the dual burden of hazard vulnerability and tenure precarity, the ROC USA model represents a promising alternative. Yet trends regarding which MHCs become ROC USA cooperatives raise troubling questions about the future segmentation of hazard risk among MHCs, especially as climate change impacts mount. Given that investor owners frequently underinvest in MHC infrastructure and sell when looming investments are required, cooperative MHC formation can provide a mechanism for private owners to offload financial liabilities onto cooperative communities. ROC USA limits its risk exposure by substantially excluding MHCs with especially high environmental risks and infrastructural liabilities from the network. What happens to the highest risk MHCs where the need to address environmental hazards and infrastructure liabilities make both private investor purchases and cooperative formation through ROC USA nonviable alternatives?

Future Research and Policy Directions

Poor communities worldwide struggle with the double burden of unaffordable, insecure housing and mounting threats from climate change-exacerbated environmental risks. Residents of MHCs face these dual challenges in acute terms. The ROC USA model presents a promising pathway for low-income households to create stable, self-governing communities. The model has scaled quickly because it enables access to resources that helps preserve housing stability and affordability while giving low-income people agency in shaping their own communities. Building on these findings as well as interviewees’ own suggestions, we identify areas where co-op support entities, like ROC USA, can better account for climate change, how public agencies can help scale up and support cooperative formation and adaptation, and avenues for further research.

Future Directions for Technical Assistance Providers and Networks Supporting Co-op Housing

This research suggests that the networked form and function of the ROC USA model is an important part of its success and scalability. We offer three recommendations for how technical assistance providers and network support organizations like ROC USA might explicitly address mounting climate change threats. Although the recommendations below are rooted in research on the ROC USA model, many suggestions are equally relevant to other forms of alternative tenure and cooperative housing, including other limited-equity housing cooperatives and community land trusts, seeking to address mounting climate change vulnerabilities at scale. Based on our research, we recommend technical assistance providers take the following steps to explicitly address climate change action and reduce vulnerabilities in shared-equity communities:

-

According to interviewees, ROC USA has developed a robust, resident-informed due diligence process. Even so, changes in climate conditions are already placing unanticipated stress on infrastructure systems above and beyond those anticipated during property conditions surveys. We recommend TA providers incorporate climate change projections into planning for capital improvements, infrastructure, and maintenance during due diligence processes to anticipate changing environmental conditions and plan necessary upgrades.

-

Interviewees suggest resident owners in ROC USA communities are more empowered to share and act on their experiential knowledge of hazards and infrastructure conditions than they would be in an investor-owned community. We recommend that ROC USA and the CTAPs further institutionalize processes for gathering and using resident-owners’ experiential knowledge, both during the acquisition due diligence process and throughout the operations of the community.

-

We found that ROC USA currently excludes MHCs with significant floodplain exposure from joining the network. Although rational, this precludes many MHCs that might benefit from resident ownership. We recommend that ROC USA develop dedicated funding strategies to provide targeted assistance to enable communities with known environmental vulnerabilities, like flood risks, to pursue resident ownership. Mitigating hazard risks in these communities would likely require additional public and philanthropic support, but collective land tenure would enable communities to reduce their vulnerability to hazards by supporting within-community relocation, whole-community resettlement, or even spreading risks, costs, and development opportunities across multiple member sites.5

-

Finally, our interviews suggest there are promising opportunities for ROC USA co-ops to mobilize around both climate change adaptation (vulnerability reduction) and mitigation (decarbonization). Several models for low-carbon manufactured housing have emerged in recent years, including the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Energy Star for New Manufactured Housing standard and the Vermod line of net zero modular homes, which was initiated by philanthropic and nonprofit entities after Hurricane Irene in 2011. Community-scale opportunities for decarbonizing MHCs include relatively straightforward changes like switching to energy-efficient LED street lighting and more complex options like investing in renewable energy production on community-owned land or buying into off-site renewable energy projects, both of which have been done by ROC USA communities (CTAP interview). Similarly, co-op MHCs can support household and community-level adaptations to climate risks through such mechanisms as providing the security of tenure to encourage homeowners to invest in upgrades like more secure foundations and improved insulation and mechanical systems for thermal comfort; enabling collective investments in upgrading community infrastructure systems including water, drainage, and sewer utilities; and facilitating shifts in settlement patterns to relocate homes away from hazard-prone sites.

Whereas funding sources for supporting climate mitigation and adaptation in low-income housing are extremely limited, there are likely to be increased resources available through both federal and state governments in the years to come. Consistent with the goals of the 2019 Congressional Green New Deal resolution (H.R. Res. 109, 2019), recent legislation in several states (e.g., New York’s 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act) explicitly targets resources for climate action and adaptation in low-income and minority front-line communities. As climate change-related public funding increases, TA providers are well positioned to help co-ops access and use these resources.

Table 4 summarizes benefits, challenges, and recommendations for building adaptive capacity in ROCs. Although interviews with technical assistance providers in the ROC USA network suggest that some network organizations are beginning to consider climate change threats more explicitly, we are not aware of any efforts to institutionalize these efforts in the ways that we suggest here.

Table 4. Adaptive capacity features, challenges, and recommendations for resident-owned communities (ROC) USA

Future Directions for Public Policy

This research affirms that cooperative ownership and self-governance are not replacements for a functional public sector in addressing climate and hazard vulnerability in low-income communities. On the contrary, well-designed public policy is essential to the growth of resident ownership and the success of ROCs as they address hazard vulnerabilities and other challenges. We offer three recommendations for shifts in local, state, and federal policy to support adaptation in cooperative communities.

-

The ability of the ROC USA model to spread is substantially shaped by state legislation. We recommend states adopt legislation to encourage the formation of more ROCs through such measures as improved notice-of-sale requirements, tenant-opportunity-to-purchase laws, and tax incentives for sales to residents, following guidance from the National Consumer Law Center (NCLC & Prosperity Now, 2021). Programs can directly subsidize resident purchases of MHCs through grants or low-interest loans, like those provided through California’s Mobilehome Park Rehabilitation and Resident Ownership Program.

-

To boost adaptive capacity in communities that need it the most, we recommend policymakers provide financial and technical support to help co-op MHCs mitigate hazard risks and invest in climate action, for instance by training TA providers to incorporate climate change into capital improvement plans, targeting Green New Deal-oriented funding toward MHCs, or creating new lending instruments through entities like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to fund community or household-level infrastructure investments.

-

The ROC USA network structure includes a central body for coordination, training, and network building, a network of certified technical assistance providers to deliver place-specific problem-solving expertise for communities, and peer-to-peer learning between co-op resident owners. This structure effectively supports member communities in building their adaptive capacity. We recommend that policymakers fund and build the technical capacity of low-income housing support networks like ROC USA, which can act as platforms for rapidly integrating climate impacts, awareness, and long-term planning into the complex institutional landscape of affordable housing.

Implications and Future Research

The success of ROC USA’s networked cooperative housing model holds insights to inform practices in other housing subsectors, including multifamily housing. Much as the consolidation of MHC ownership by large, well-capitalized investor-owners threatens the housing stability and affordability of MHCs (Sullivan, 2018a), urban revitalization, the financialization of single-family housing, and the COVID-19 pandemic have accelerated evictions and increased the precarity of residents of other forms of housing. These threats, along with climate change, compel researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to identify viable alternatives that protect housing affordability and advance community control.

Future research could more systematically compare ROC USA communities with standard MHCs and independent co-op MHCs, whether through fieldwork, large-scale survey data, paired case studies of ROCs and nearby nonresident-owned communities, or longitudinal studies following communities before and after co-op formation and before and after hazard events. Such studies would offer deeper insight into the strengths and weaknesses of co-op MHCs. Research could also explore the feasibility of extending ROC USA’s network-supported cooperative model to multifamily housing.

Scholars of climate change adaptation have long advocated for transformative adaptation that goes beyond hazard mitigation to address the root causes of uneven vulnerability (Pelling, 2011). Such transformations “depend on who has the power to act” (Romero-Lankao et al., 2018, p. 754). Regardless of their ownership model, manufactured housing communities face elevated vulnerability to hazards because of their heightened exposure and sensitivity. These vulnerabilities make it all the more important that residents can respond effectively using their own agency and external support. By enabling the transformation of MHC residents from precarious halfway homeowners (Sullivan, 2018b) into empowered self-governing resident-owners, the networked co-op model advanced by ROC USA supports low-income communities in developing the power to act in the face of climate change and other crises to come.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Lawrence Vale (MIT) for his early and sustained support for this project, Carolina Reid (University of California, Berkeley) for her comments on a draft of this article, and Natasha Cheong (University of Toronto), Osamu Kumasaka (MIT), and Logan Leeds (Cornell) for their research assistance. We also appreciate the staff at ROC USA, technical assistance providers, and housing cooperative leaders who shared their time and knowledge with us. We sincerely thank Michael Donnelly and Steven Guggenmos at Freddie Mac for sharing data from their 2019 report. Finally, we thank the two anonymous reviewers whose close reading and comments helped us to clarify and strengthen our arguments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Funding from the Leventhal Center for Advanced Urbanism at MIT, along with Cornell University’s Department of City and Regional Planning, University of California, Berkeley’s Department of City and Regional Planning, and University of Toronto’s Department of Geography and Planning, supported this research.

Notes on contributors

Zachary Lamb

Zachary Lamb is an assistant professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at University of California Berkeley. His research focuses on how urban design and planning shape uneven impacts from and adaptations to climate change.

Linda Shi

Linda Shi is an assistant professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at Cornell University. Her research examines how land governance institutions shape the equity and justice of climate adaptation.

Stephanie Silva

Stephanie Silva is a Master in City Planning candidate in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT. Her work focuses on the design and implementation of more equitable climate adaptation and housing plans.

Jason Spicer

Jason Spicer is an assistant professor in the urban planning program at the University of Toronto. He researches alternative economic ownership and governance models.

Notes

- 1According to industry groups, some 37% of new manufactured housing units are placed in manufactured housing communities (MHCs), also known as mobile home parks or trailer parks. The remaining 63% are on private land (MHI, 2020).

- 2The concept of climate resilience has been critiqued as glorifying self-sufficiency among the poor (Davoudi, 2018), but grassroots and other advocates have embraced the term and define it as addressing underlying drivers of climate vulnerability (Shi, 2020).

- 3Census-defined metropolitan statistical areas include less dense, exurban areas. Nonetheless, at the regional scale, the housing and labor markets of these exurban areas are closely related to those of more conventionally defined, high density urban areas, which is one reason why they are identified in White House Office of Management and Budget metropolitan statistical area classifications.

- 4The ROC model’s strength in New Hampshire exemplifies path dependency in planning and development processes (Sorensen, 2015). In the mid 1980s, leaders at the NHCLF and the University of New Hampshire developed the co-op model using a supportive state legislative environment and access to philanthropic capital from a religious organization. After the success of early co-op conversions, the adoption of the model accelerated because of a change of state law requiring MHC sellers to provide residents with notice and an opportunity for purchase (Bradley interview). A recent podcast episode produced by ROC USA tells this story in greater depth (ROC USA, 2021).

- 5Whereas some observers may regard the presence of relatively high-density MHCs in hazard-prone environments as problematic, the relationship between density and vulnerability can be complex. In many cases, increasing local density can actually reduce the per-household cost of collective hazard mitigation (e.g., fire suppression or local flood mitigation infrastructure).

Comments

Penny Dever-Reynolds

June 6, 2024, 4:16 pm

This is very helpful ... we are an over-55 MHP in urban Albuquerque, suffering under private investor landlords. We hope to encourage NM legislators to pass legislation enabling ROC. Thank you for this useful study!

Josh Davis

June 6, 2024, 4:42 pm

Glad you found it useful! Neighborworks and ROC USA are great groups to connect with, if you haven't already. Best of luck on the legislation!

Add new comment