Built from the belief that the music industry no longer serves artists or listeners, Mirlo is pushing for a radical, federated, and decentralized reimagining of how music is shared online.

[Editor's note: we interviewed Mirlo co-founder Alex Rodríguez last year. You can watch that interview here.]

Originally published at DIY Conspiracy

Trying to stay consistent at running a DIY punk website for years often brings me a weird kind of pressure and internal conflicts: the routine of reviewing as many records as possible, the inertia of keeping up with the endless stream of new releases. And while I always care about lyrics, politics, and the band’s overall background, message, and context, in the end most bands and labels sending me music still feel like they’re grasping for attention in a world where the collective attention span is almost zero.

Despite all the embedded politics in punk, DIY Conspiracy can still end up looking like just another music website with reviews and interviews, feeding free traffic and implicit endorsement to Bandcamp, YouTube, and other platforms. Smaller DIY bands upload their music to the same centralized, corporate infrastructures as everyone else. With today’s extractive capitalism and the ongoing enshittification of social media and everything else on the web, it often feels like punk is also losing its autonomy, and that most bands don’t really try to challenge the ways they distribute their music and message online.

What gives me hope, though, are not only the growing list of bands boycotting corporate platforms that invest in AI, military tech, and surveillance, but also the growing efforts to find alternatives in decentralization and federation; the attempts to reclaim control and autonomy through tools like Mirlo, Jam, Bandwagon, Ampwall, and others. What we need is not just another corporate structure with a different logo; we need to correctly identify the root problems as capitalism and extractive economies.

With this in mind, I reached out to Louis-Louise Kay of Mirlo. LLK is a French musician and organizer who has composed music for games, movies, and animation, and who also records solo under the moniker MOWUKIS.

Mirlo (“black bird” in Spanish) starts from a simple proposal: the music industry does not work for artists or listeners, and it needs a radical reimagining. Two years in, Mirlo hosts a small but growing community of artists, listeners, organizers, and coders who are trying exactly that: taking lessons from mutual aid and militant political organizing and applying them to a platform built cooperatively.

Today, Mirlo is building an online audio distribution and patronage platform that aims to be radical, accessible, open-source (free & prix libre), modular, and based on open standards. Let’s learn more about it.

For everyone who’s new to Mirlo, can you start with what it is and why you started building it?

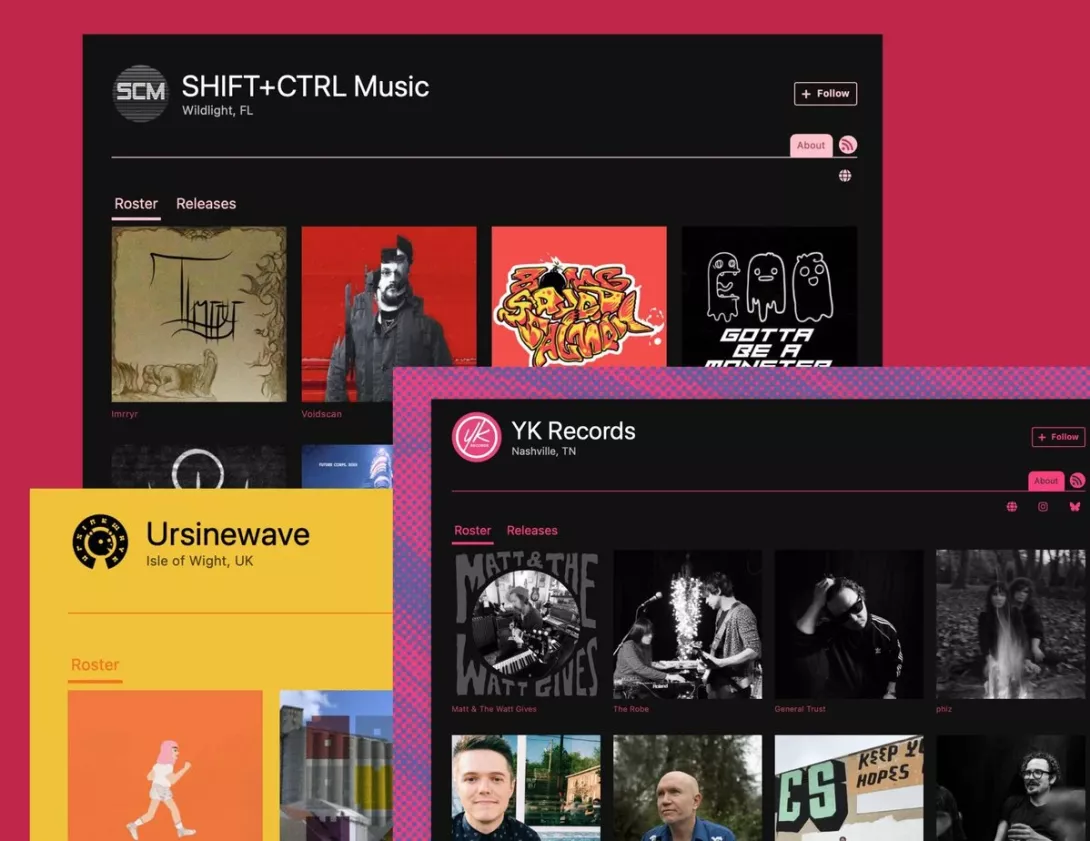

Mirlo is an alternative to Bandcamp. It is built free and open-source by a group of coop workers—we are set up as a coop—but also through mutual aid with the participation of many volunteers who’ve helped with marketing, user experience, design, code, and everything else about the platform.

We created it because we’d previously been involved in other efforts to build a better, more sustainable, more ethical, more user-controlled music distribution service at platform cooperatives like Resonate and Ampled (Ampled was a music focused subscription service à la Patreon; Resonate was closer to Spotify but with a different business model). The coop itself is based in the US, since its two worker owners, Alex and Simon, live there, and as a collaborator based in France since the inception of the project, I’m what we’ve decided to call “a Steward” of the coop alongside a couple of other steward members, a status that grants us equal voting rights despite not having shares in the worker coop. Ultimately we’re all unpaid volunteer workers though, the differences between the two statuses are more about the way we relate to the coop legally.

We started thinking about Mirlo around a time where both Resonate and Ampled were starting to have issues figuring out their future and we wanted to try out things that didn’t always feel completely aligned with what those platforms initially set out to do. After a while both projects eventually ended up closing or winding down. We felt it was the right moment to take what we liked about them—both conceptually and code-wise since we’d worked on some open-source code along the way—and bring it into a new space where we could try doing things our own way. We wanted to use our experience and analysis of what we’d seen there and in other works we’d done outside of the music ecosystem in militant and political spaces, cooperatives, or mutual aid groups, and bake all that into Mirlo.

The initial goal was to create something quite simple and build tools that artists could immediately use, so we decided to build a music distribution service that emulated Bandcamp. It felt the most reasonable basis to work from, because Bandcamp’s business model as an online digital music shop is ultimately quite straightforward, and we wanted to do something that already made sense, was proven to work for artists, and was perceived as a somewhat sound and ethical baseline. If we wanted to provide artists with something that could be meaningful in their lives right away, it felt like this was the best starting point.

So two years after launch, this is where we are now: we’ve got a free and open-source service run by a workers coop that emulates Bandcamp. People can choose the fee they want to give us, or keep all the money from their sales, it’s setup at 10% by default but they can manually set it to 0 and even decide variable fees for each of their releases if they want. The entire code the platform itself runs on being free and open-source means people could potentially even use it to build their own platform with it.

Now that we’ve reached that baseline and the service is almost becoming feature complete, we want to branch out into figuring out the things we’ve been thinking about since our days at Resonate and Ampled—federation, decentralization, experimenting with governance models, exploring how far mutual aid can take us and where it hits limits, and figuring out the best way to keep a platform like Mirlo running without needing to scale to huge proportions. “A free and open-source Bandcamp” was our starting point, but it was always just a way for us to build towards where we’d like to go next.

When Bandcamp started, they got a few million dollars of venture capital money. Most other “alternatives” today are repeating the same story and taking venture capital, while Mirlo is a completely different model based on mutual aid and the solidarity economy. But the biggest challenge for this model is sustainability. What makes the platform sustainable?

For us, not taking investor money early on was really important. And I don’t even want to say investor money, because investor money might imply huge sums, but we didn’t want to take any money at all beyond direct donations—we did make a Kickstarter campaign during our first year that got us 15k and that was it—if it would have meant taking away ownership from the people doing the work. We wanted to first figure out what we were capable of doing with as little as possible. One of the things we thought about early on was that we needed this to work on a very small scale. We needed to be able to host the music for a few hundred people, let them sell it, and have the business model already work as it was. The hope was to have a community of artists we could work with, experiment and try things out with, without feeling the pressure of answering to investors or catering to a huge number of people we couldn’t possibly manage this quickly.

Mirlo was always rooted in smallness. We wanted to keep things small for as long as possible, avoid the need to build momentum to release the product with a big bang hoping for massive adoption, and instead keep slow growth and openness at the core, working at our own pace while sharing what we’re working on, which includes sometimes sharing your struggles. We thought that if we tried to scale too fast, we’d quickly run into the issues you mentioned—figuring out business sustainability in a hurry, which can push you to make decisions that don’t match what you believed in and what you started this project for initially.

For now, this means we are mostly sustainable through donations. That is our main resource, and donations are what keep the platform afloat. The other thing we rely on is the work of volunteers. And then the question in these projects often becomes: how do you organize volunteer work? Free work is only sustainable until someone burns out and can’t do it anymore, so the human element is front and center in our approach.

That’s where mutual aid experience and being very mindful of the work volunteers put in becomes really important. We need to be organized in ways that make people’s work feel genuinely exciting to them. It shouldn’t feel too daunting, too depressing, too lonely, and people should always feel like they can just walk away from it and it’s ok. So this implies, on our end, that we need to also manage people’s expectations, and let them know that yes, it might take us a little longer to fix a bug, or to answer on socials, because we try to prioritize our own well-being and freedom.

And despite all that, working on Mirlo can still be very tiring, it’s a lot of work, so we’re really invested in figuring out more long-term strategies for this to not just be “our” project, and expand beyond the core team. We want other people to join us in figuring this out, or make use of what we build and expand on it by themselves, so that it grows in multiple ways beyond our original vision, while allowing us to still experiment with our own ideas.

Mirlo has recently received a grant from the Dutch foundation NLNet to federate and build Fediverse features, if I understand it correctly. For non-technical people, what does “federating” actually mean for musicians and labels, and what will this funding allow you to build?

I think that even for technical people this is an interesting question. Federation is not just Mastodon integration or ActivityPub. When we say we want to integrate with the Fediverse, that’s true, but it can mean different things. We want artists to be able to share blog posts and releases outside of Mirlo, and for people on Mastodon—and the Fediverse more broadly, which is full of artists—to be able to find, follow and interact with Mirlo from wherever they are. But that’s really just one aspect of it.

The other part is that we also want to figure out a way for different music platforms to connect with each other, and that’s a different kind of work. Right now we’re already seeing many platforms appear with different interesting takes on what “a better Bandcamp” could be, but they don’t talk to one another. They have isolated catalogs and search engines, and they’re all fighting to get people’s limited attention to grow their userbase, which in turn means that even if they don’t want to be, they end up competing for the same scarce resource.

On our end, the thing is, we are firmly anti-hegemonic—anti “one big platform to rule them all”—so this is not the kind of battle we want to be fighting, and in that spirit we’ve been trying to reach out to other platforms and figure out ways to build things more cooperatively. We’ve already had many encouraging conversations with other likeminded platforms like Jam, Ampwall, or Bandwagon about figuring more of these things together and helping each other out. This is where the ethos of federation can also become useful to us, despite the context not being social networks or Mastodon.

We’re trying to find a way to federate these music marketplaces and music distribution platforms so that you can follow, purchase from, support and search for artists across many different ethical platforms from many different places on the internet, and still have a painless music listening experience doing it. That’s very different from simply following an artist on Mastodon. It means platforms need to talk to one another, understand how each other’s technologies work, and find ways for actors who are not always used to collaborating to actually figure things out together. As you mentioned, the music industry and music distribution world often follow a startup ethos: get money, get users, grow big. This is the pattern we’d like to break from.

We’re trying to build with protocols and tools in mind, make things that people can install on their own websites or build their own collective platforms with, but that you could still access from Mirlo and other like-minded websites. Instead of one Bandcamp to rule them all, you’d have all sorts of music shops that could interact with one another, all living in one easily accessible ecosystem that you could reach from all sorts of places. And if the platform instance that hosts your music starts to do things you don’t like, you should be able to take your data out of it, transfer it to another instance, and not lose anything in the process. And once we figure that out, we can see where it takes us and how ambitious we can become about transforming the way online music distribution works.

Can you talk about the self-hosting opportunities you mentioned, if I understand correctly?

Sure. Right now we’re focusing on making it possible for collectives to host their own Mirlo instance, that is, spin their own music distribution platform like Mirlo. But self-hosting for individual artists is definitely also on our mind. Currently, the best way to do this is a tool we have a lot of appreciation for called Faircamp—it’s a “static website builder”, which basically means that as a musician you take your library of songs, organize them into folders and in one click you can build that into a website. That website is like a simplified version of Bandcamp that you can self-host. It’s a great offer. We’ve talked several times with Simon Repp, the lead coder behind it, and we really admire his work.

What we’re trying to do with Mirlo is find the bridge between this approach, which we love, and Bandcamp’s affordance and simplicity for the listener—having an account with your collection on it, being able to browse all the artists using the service through one unified portal or a well-made app, being able to wishlist albums and follow artists and listeners, those kind of things. We’re trying to find the in-between. We want people to be able to self-host; several instances, several shops hosted by labels, single artists, or music webzine; And we still want one place where listeners can check their collection and search or browse across all these instances without needing to worry about the tech side of things. Figuring all this out will definitely be our big focus for next year.

I’ve heard that Mirlo has already attracted people from the Fediverse community and from the Creative Commons (CC) community, but this interview is for a DIY hardcore punk zine, and I still don’t see many proper punk bands on Mirlo. How do you envision Mirlo empowering small communities like local punk scenes, DIY labels, or just groups of friends who want to control their own digital music infrastructure?

We already have some DIY enthusiasts who are trying to set up their own Mirlo instance, so they’re basically going to make their own little version of Mirlo and help us test things out. The way we want to empower people is by giving them tools they can use to figure out for themselves how they want to organize at their level. We don’t want to dictate to everyone what the best way is for them to work together. It’s up to them to govern their instance and figure out how they want it to work.

My personal take on empowerment is that I’d rather offer strategic tools that can be used to help different communities build different things, than enforcing structures that I personally think are good on literally everyone just because that is what seems to work for me. Mirlo is set up as a cooperative of workers, because at our scale, we think it’s the best model we could use, and it has room for growth. The Mirlo cooperative takes care of the people doing the work at Mirlo, and that’s something I appreciate about the way we handle governance: we know each other and understand each other’s realities, we appreciate working together and figuring out the best way to collaborate within that structure. But if people have other needs or a different idea of how organizing their collective effort should work, we want to offer them ways to build alternatives easily with minimal effort, while remaining a part of the same music ecosystem.

I wouldn’t want Mirlo to scale to a point where it becomes powerful enough to dictate to a punk band somewhere I’ve never been how things should work just because I happen to own their data and need to keep them locked into my platform in order to secure my business. I feel like we got used to platforms being able to do that for the sake of convenience and I don’t see it is our role to go that way. I’d rather make it easier for everyone to be part of the same network made of many different labels, subcultures, and grassroots organizations, all figuring out their own structures. Then we can talk to each other and build a space where we facilitate discovering each other’s work more easily.

As for Punk music, I’d really like to see more of it on Mirlo! I’ve always appreciated the political aspects of the punk movement, the ethics behind it, and I feel like the music itself that we label as “punk” is more of a byproduct of that ethos than at the center of it all. There’s a lot of music that’s punk to me that people probably wouldn’t perceive as such. There’s a notion in it, that you should always think about the kind of compromises you can make for the sake of “art”, because your art practice should somewhat reflect what you’re aspiring to become as a person, and I like this idea that the “how” matters just as much than the “what”. I hope more people start thinking along those lines and think of how the way they distribute their music, the way they make their music, and the way they talk about their music all have an influence on the world—and an influence on themselves as well, and are ultimately part of the art they’re making. I really hope we can bring in more communities that try to be mindful of that. And it’s really not just punk music at all, although punk has historically been known for it.

One last thing I appreciate about the DIY punk scene is that sense of smallness I mentioned earlier. People organize best when they know each other through a shared reality. When it’s a small subculture that understands why things work, what makes it special, what makes it specific to a locality.

Most people don’t want to know anything about servers and hosting. They just want a new Bandcamp that won’t sell out to Epic Games, Songtradr, or some other corporation. So there are now alternatives like Subvert, offering similar features and usability while presenting themselves as more democratic and transparent. What do you think about them?

The first thing I want to say is that I completely understand the desire to build something that we already know works. It’s true most people don’t want to bother with tech or self-hosting. I think that’s one of the realizations of the last ten years on the internet. Many people have tried to get others to self-host things, and the global reaction is that most people are simply not interested. They don’t want to do it, and even if you explain the value in it to them, it’s still too much work—and at the end of the day, a lot of people just want to publish music online and haven’t chosen that battle. That was one of the reasons it made sense to start Mirlo as something that felt “just like Bandcamp.” and was rather centralized in nature.

Because for all our talks of federation, right now Mirlo is fairly similar to Subvert and other alternatives: you can come to Mirlo, create an account, create one or several artist pages, we host your music, and you distribute it through one platform that has your data and that you’re not directly in control of. You basically trust us not to sell out the way Bandcamp did, and not to do union-busting the way Bandcamp did, and hope for the best. We already offer that service, and I’d be fine if Mirlo in the future becomes just one out of several big instances in a network of similar services, much like you can create an email address on a number of services right now and people are fine with it. I can imagine one Mirlo instance per country, for example: if you’re in France, you join the big French Mirlo instance; One of our members is thinking of creating an instance in Chile and figure out what Mirlo could be like there because they have very different realities that need to be accounted for. Ultimately, joining these “big instances” and not bothering about the tech side at all will very much still be a possibility, much like most people I know who are on Mastodon have joined the bigger instances and in that sense, it’s still a partially centralized experience to them.

But “Decentralization” is a loaded word, and I think we should always remember that no matter how much a “tech” claims to be decentralized, other kinds of centralization mechanism will always happen through other means that are non-tech related but social, political, material, and we should accommodate that to some degree. For example, we could argue that right now, one of the most easily accessible forms of “Decentralization” would be for people to download the music they’ve bought, but the reasons they’re not doing it are not really tech related.

As for the idea of having one big platform to rule them all—whether it’s Subvert or another attempt—to replace Bandcamp with a more ethical version of it, I think that’s a different approach entirely. In Subvert’s case, the core idea seems to be “If Bandcamp were a coop, it would fix most of its problems,” that the problem with Bandcamp is basically its corporate ownership model.

Speaking for myself, while I do agree that Bandcamp’s corporate structure is a big issue and one of the reasons we find ourselves in that situation, my analysis as to whether making it a coop would entirely fix its issues is a bit different. For starters, if we disregard everything that’s wrong with its corporate ownership, Bandcamp as a service is not really broken, and it still functions pretty much the same, if not better, than before the buy outs. So in a way, it seems to resist enshitification so far, probably because its business model “just works” and its dominance ensures it doesn’t need to reinvent itself too much to keep growing.

So what you’re trying to fix is not necessarily the product itself, but how it’s managed. Which means the question becomes “is doing exactly the same thing but through one giant multi-stakeholder coop necessarily going to mean that people will feel more empowered and will have a better sense of ownership of their platform?”.

Based on my experience with coops, it’s important to keep in mind that they’re not magical and they’re extremely context dependent. I’d love for the cooperative movement to get stronger, and I’d love it if we could have more worker ownership of companies. I would actually love to see a world where coops are the default form of companies! But I don’t really buy into the idea that coops can solve all the problems in a world ruled by capitalism.

A coop still has to compete in the marketplace with capitalist entities. That doesn’t change because you’re a coop. You still have to deal with all the shit capitalism throws at you. That’s why I have my doubts that a new hegemonic platform to replace Bandcamp or Spotify or whatever is a solution in and of itself by virtue of being setup as a coop.

A governance model that handles thousands or even millions of users from all around the world, with vastly different material, financial, social, and cultural realities, each with competing desires—I can see it becoming very complicated very quickly. If you were absolutely set on creating “one democratic structure” for all these people through one business company, I’m wary you’d quickly end up creating something that looks like a sort of music “state”, with necessary elections, layers of hierarchy, people competing for positions of power within their own subgroups. These systems and companies exist, and some of them do function, but the bigger they grow, the less agency you get as a simple member and the people who are most fluent at managing this complexity will inevitably have more power than most.

More importantly though, in the very case specific context of a music marketplace you would have to manage the fact that listeners, workers, shareholders, and musicians all have wildly different realities, capacities and needs. There’s no simple way to put them all into one structure and expect it to work for everyone. Cooperatives are usually structures that mostly handle workers, and that shared experience of “being a worker” is what makes the grouping meaningful, but musicians on a marketplace are a very different kind of entity to handle.

That’s why the way I view it, at some point it’s not really the governance system that causes the issues and frustrations for those who feel left out, it’s the scale of the entity that needs to be governed over. This being said, I get why “rebuilding Bandcamp but as a cooperative” remains an enticing ethical argument, so I don’t want to say projects like Subvert are making a bad call, it’s worth a shot, and there are many different ways that people are currently trying to tackle these issues. But I wanted to outline the reasons why I personally thought it was also interesting to be part of a project that explores other paths that break free from this approach.

And while we’re watching closely what others do, we’re also trying to be self-critical of our own limits. As you said, we do ultimately struggle with money too and still need to figure out how to exist within an increasingly hostile capitalist environment. We’d need more donations, more people buying music on Mirlo. Even at our current scale, we could use more support. Being a bigger platform would probably make funding ourselves easier, but what we want to figure out is how people can come together and govern over themselves—and their differences—without the need for massive fundings.

Either way, there will always be a problem to solve, and that problem is usually called Capitalism. And we’re all trying out different ways to figure ourselves out within that context.

From piracy like Napster and torrents to streaming platforms and now all the AI hype, musicians and artists are always affected by cultural and capitalism’s shifts. How do you see remuneration for musicians and artists on platforms like Mirlo?

The remuneration of artists on Mirlo is similar to Bandcamp. It’s very simple. Artists can promote their page, sell their records, and offer subscriptions where people choose a tier—something similar to Patreon. There are different ways people can tip musicians. Any time you listen to music on Mirlo, there’s a tip button where you can immediately support the artist if you like what you hear.

We try to keep it simple. We’ve aggregated a bunch of things artists already use—subscriptions, album purchases, merch shop, tips—and combined them into one interface that makes sense to us, to listeners, and to artists alike. There’s no complex, revolutionary system to fund artists. Every time I see a complex new business model claiming to revolutionize how artists make money, I tend to find it gimmicky.

At the end of the day, artists are struggling with a fight for attention and for people’s time, and there’s no way to make that disappear easily with a new business model. That’s why the solutions we offer are the same things artists have already been using elsewhere. Sometimes they work well; sometimes they don’t. We’re aware of that. We just want to find ways to at least make them work better when they do.

Maybe in today’s system there’s no way for an artist to make a living from any digital platform. There’s this constant struggle for attention, and in the end you just want to be able to play live/tour, sell some merch, and be known out there.

I think music, of all things right now, is the most devalued. Music has long been culturally considered something free, and today it’s not something people pay for anymore. And even though this is happening in other art forms, there’s still a difference. You still have to subscribe to multiple streaming services to access series or movies. You can pirate them, of course, but that can be cumbersome or complicated, e.g. you’re not sure you’ll find subtitles in the right language, one episode of your favorite series’ missing, so it becomes frustrating. And you still have to pay a substantial amount of money to access things like video games. Those things still have value, even if that value is decreasing over time. But with music, it’s very hard to find anyone—unless they’re an absolute music enthusiast who buys tons of new music—who purchases anything at all.

This creates a weird market. Live music, which you mentioned, is now congested. There are too many people trying to make it through live shows, and even some decently successful artists mostly tour because they enjoy it or because it’s a way to reach out to new audiences, make yourself known, and create connections with other artists or art workers. But touring itself doesn’t necessarily make them much money anymore. If they break even at the end of a tour, that’s already pretty good.

I think we’re in a moment where music is simply not a great way to make money. You can get lucky; you can make some money by having a big opportunity if many other things align or through copyright, which is one of the last remaining avenues that can make substantial gains without destroying your work-life balance. But other than that, it’s incredibly hard. What most artists end up doing is building a community around themselves that is not just about the music.

Because as it stands, most of the people I know who managed to build a life as musicians have subscribers or multiple revenue streams. They do other work like video, or do music for video games. They teach lessons. They run YouTube channels or podcasts. They are really multifaceted. If you describe the kind of work they do, music might not even be the main thing they spend their time on. It’s how they think of themselves, as musicians, but it’s not necessarily what they do most of the time.

That’s why I like the way UMAW (Union of Musicians and Allied Workers) is reframing this problem lately, basically saying that if we want a fairer landscape, it’s not about a new business model or a new fairer company taking over, we also need to take it to state legislation and rethink the law around how money made from music is redistributed, so that we figure out as a society the kinds of limit we want to oppose to extractive capitalism in the art world.

This makes me think that, in the end, the struggle is for autonomy—and decentralized platforms like the ones you’re building are tools for musicians to regain that autonomy from corporations that have been using their music to get rich.

Yeah, we’ve been talking about empowering DIY punk scenes, and I often like to think of the kind of tools that could help generate or encourage new behaviors. For example, if there was a DIY Conspiracy instance of Mirlo—a DIY Conspiracy music shop—I hope it would help people there feel more closely connected to each other because it would be “their own place”, establishing a direct relationship out of building something together.

Maybe you’d start figuring out your own ways to pool money and redistribute it at your own scale. Maybe the DIY Conspiracy instance has only 100 people, but everyone is putting in work to make that instance function so you set up your own donation and fee system that goes to support DIY Conspiracy, pool the money, and try to redistribute it within your community, in ways that might work better for you. The idea is that people can figure things out at this sort of medium scale.

It’s not redistribution at a scale so enormous that it becomes hard to grasp, manage and interact with. It’s doing it with a group of people who know each other to some extent, who share a common interest or are part of a local community, and who want to use this tool to provide for each other. I think in a lot of contexts that’s just more manageable. You can feel more empowered at that scale. And it’s easier to redistribute because you actually know who is around and what they’re in it for.

That’s how I see this idea of changing the narrative. The problem for an artist joining one big platform is that precisely because the platform is so big you kind of end up on your own. It can be both a good and a bad thing. Something I appreciated while working on Mirlo, was getting to know who the people around me were. Mirlo might be somewhat small, but because of it you still feel surrounded by people you can understand and build community with. In that sense it felt less lonely to be on Mirlo—even if it only has a little over a thousand artists—than on a big platform with all the music in the world. Nurturing that feeling and figuring out how we could expand while preserving it is part of our goal.

So my hope is that grabbing these tools and building things together can help people decenter themselves and think of what they’re doing as more of a collective effort. And that it will push them to think about governance, money, cooperation, at scales they can meaningfully manage: How do we finance this thing we don’t want to see die, because we like being together, we like hanging around together, we like doing things together? This feels to me like the sort of impulses musicians already naturally have when they start a collective, form a band, make a label, and that they have to abandon once they need to setup a shop and distribute their art.

That’s how I hope decentralization can bring people into new mental spaces—rethinking what they’re doing when they post music online. Thinking of it as doing it with other people, rather than isolating themselves, and trying to game a system that is designed to have more losers than winners.

I guess you still need quite a lot of support. What are the ways people can help and support Mirlo?

The main way to support us is simply by purchasing music on Mirlo. Many artists kindly choose to give us a fee on their sales, so anytime you buy their music, we get some funding from that and it makes us happy because it means musicians are actually making money in the process.

The other way is donations. Early on, we thought it would be great to use the same tools we offer to artists to help sustain ourselves. So we created our own Mirlo page, and people can donate and support us through Mirlo itself. Part of the reasoning is that by using Mirlo’s own tools to empower ourselves, we’re constantly testing and using our own platform—and it pushes us to keep improving it in ways that are aligned with actual use cases.

For example, we recently added crowdfunding features, out of sheer necessity because at some point we needed to crowdfund something and we didn’t want to go through another crowdfunding platform. Now we can make that feature exist for everyone. So the way to support us is to go to mirlo.space and hit the donate button on our page. You can tip us once, or you can donate monthly; obviously monthly helps us the most. I would really love to have more supporters, because that’s the best way for us not to depend on complex grants applications, to be able to maintain the platform and put in the kind of work we want to do.

Comments

Offerz

January 28, 2026, 2:25 pm

I'd definitely give it a try. Both Bandcamp and Spotify have disappointed me.

Josh Davis

January 28, 2026, 3:07 pm

Check 'em out here: https://mirlo.space/

Add new comment