Introduction & Preface | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 9 | Chapter 10 | Chapter 11 | Chapter 12 | Chapter 13 |

Translator’s note:

Should every member’s vote be equal? One Member, One Vote is such a bedrock principle of cooperativism that the question itself seems heretical. Worker cooperatives are subject to constant pressure to abandon democracy and labor sovereignty, member power should be defended, not doubted. And yet, we have all seen the emergence of bureaucratic tendencies of separation of management from labor in worker cooperatives, loss of the cooperative spirit, formal democracy subverted by informal hierarchy. What are the sources of this tendency? How might they be addressed? Is affirmation of the egalitarian principle – OMOV – enough?

In previous chapters, the author made an argument for the rigorous measurement of member contributions to the worker cooperative enterprise, going beyond the simple measure of hours worked to take into account member contributions to equity as well as differences in skill and expertise. In the interests of fairness and efficiency, he argued, and in keeping with the principle of patronage, distribution of surplus should be made on this more precise, but less egalitarian, basis. In this chapter, Luis Razeto extends the argument to the realms of governance and management, proposing a system of proportional voting in an organizational structure in which decision-making power and participation are distributed differentially, based on member contributions, in accordance with criteria of efficiency, justice, and democratic participation.

Razeto is not the first to question OMOV. In an interesting episode, Mondragón founder Arizmendiarrieta, editor of the newsletter Trabajo y Unión, pseudonymously authored competing letters to the editor, for and against the “qualified vote.” One denounced the notion as a paternalistic fraud, a kind of “aristodemocracy” that would amount to “giving weapons to those who are already best armed.” The other argued that OMOV was “dehumanizing” because it treated members as uniform abstract units, disregarding their particular skills and qualities and ignoring the role of education in raising workers skill levels. Voting is a tool, it argued, not a dogma, and “effective and bold management” required giving greater weight to the views of leaders and the most skilled. (See Voting and Democracy at Mondragón, in Cooperatives at Work, pp. 60-62, Cheney et al. Emerald 2023.)

An economic theory adequate to the cooperative experience requires rethinking, even of concepts we hold dear. This is not to ask the reader to accept Razeto’s proposal, just to put dogma aside as you sort out your own position on this crucial question.

- Matt Noyes

Chapter 7

The power to govern and manage in a workers enterprise.

1. We now face the question of “power” and the right to govern and manage an economic unit, a question intimately related to the problematics of property, financial resources, labor, and the distribution of surplus. “One member, one vote” is an established part of cooperative doctrine, as the principle of governance most aligned with, and representative of, the democratic orientation of the cooperative movement and its social and moral values. And, if we consider a cooperative’s capital to be common property and assume that the work is equally shared by all members, egalitarianism would appear to be the obvious and theoretically apposite principle of management.

And yet, in practice, the problem of power is more complex, and at times obscure. How many cooperatives have little member participation? How many, in spite of the formal equality represented by the General Assembly of members, are run by bureaucratic groups at the management level or on the board? In most cases, the latter occurs not due to bad intentions or narrow individual or group interests, but because relatively efficient operation of the enterprise requires it.

Our purpose here is not to discuss the limits and problems particular to a system of management characterized by “direct and egalitarian democracy,” but to consider the theme of power from the point of view of the economic logic and rationality of the workers enterprise, in keeping with our overall approach. The adoption of an ownership structure and a mechanism of distribution of profits of the type we have suggested has indubitable implications for the management and governance of this type of enterprise, which must be made explicit. The problem is complex and needs to be examined carefully, avoiding the confusions to which an ambiguous and imprecise use of concepts can give rise.1

When analyzing the economic factors and categories of an enterprise we distinguish between the organization’s business activity and the specific function of administration and management of operations. The first corresponds to the organizing category, which determines the general objectives of the enterprise and subordinates or employs to its own ends the other factors that it incorporates and “hires.” The second is the specialized function of a particular economic factor that we have identified as “administration” or management.

Thus, it is necessary to clarify first of all that in a workers enterprise control over general organization and governance, that is, “power” or maximum authority, rests with the category Labor (represented by the collective of worker members). In a community enterprise, it rests with the category Community (represented by the community members who organize the enterprise). In both cases, the risks are born by the organizing subjects, who suffer or enjoy the consequences of poor or effective operations. If the economic objective of the enterprise is the maximum valorization of Labor – or of the Community – then the only economically rational power structure is one in which ultimate decision-making power is held by the worker members, or the community, themselves.

Management and administration of operations can be assumed directly by the organizing category, but it can also be contracted out by hiring an executive director, manager, management team, etc. Without a doubt, managing also implies a certain level of decision-making power in the enterprise, following the guidance of the directors and always in alignment with the objectives they have set. If management is directly exercised by the organizers of the enterprise, either collectively or by one or more person, we say that the management factor is internal, belonging to the enterprise. If the organizers of the enterprise hire executives or managers from outside the enterprise, the management factor is external, a cost needing to be added to the firm’s operating budget. In either case, management is to be exercised in alignment with the objectives set by the organizing category.

Workers (or a community) who decide to manage the enterprise themselves or to assign that role to third parties, are making a choice, taking into account their own convenience, the costs implied by each approach, the benefits to be obtained, and their own degree of capacity to manage. Which approach is best is not, then, an important conceptual problem for all enterprises of this type, to be resolved on the level of theory, but a practical question requiring particular analysis of the efficiency and realism of each option, a question that must be answered by the organizers themselves.

The theoretical challenge, which deserves patient examination, is posed by the question of decision-making “power” in general. Since the category Labor is not embodied in one individual but in a group of workers, all of them, by virtue of being members of the organizing category, should participate in that power to some degree.

The same must be said with respect to the category Community, although with respect to Community the problem is simpler: since the subject is a collective one, its decisions are naturally expressed through governing bodies. Labor, on the other hand, is a category constituted cooperatively by the workers – a group of people who retain their independence and participate in Labor to different degrees. Let us take our time with this problem.

As we know, as the organizing category of the cooperative enterprise, Labor presents itself in two principal forms: as direct labor performed by the workers themselves and as labor that has been accumulated or objectified in the equity of the enterprise as an internal factor. As direct labor, it shows up in the different number of hours worked by each worker and the different functions they perform in accordance with their different levels of skill and types of technical qualification. As accumulated labor, it also differs in the amount belonging to each worker, as not every member participates in the equity equally. Some members have more accumulated labor than others due to their length of service as members of the cooperative or due to the greater or lesser contributions to equity each has made, measured in units of labor. The theoretical problem consists of determining if these qualitative and quantitative differences should or should not be reflected in different levels of “power” or governance authority in the enterprise.

In terms of strictly economic logic the answer must be positive, since the units of labor which each member contributes directly to the cooperative, or adds to the equity, determine the degree of personal risk that each assumes with respect to the operations of the enterprise.

This is more obvious in cooperative enterprises than in private corporations because “labor shares” have no commercial value, nor are they traded on the market. Thus, the income that the subjects obtain through share ownership depends solely on the results of business operations, that is, on the administration of the business. The same thing applies to the direct labor incorporated into the process, the remuneration of which is not predetermined, but instead varies with the sum of the surplus generated.

If we do not recognize a proportional distribution of “power” in accordance with the effective contribution of each member to the enterprise, the property rights in the product of one’s own work will remain limited to the possibility of withdrawing the value one has accumulated, when leaving the enterprise. The member will not have the right to direct the enterprise in proportion to their contribution. In such circumstances, members who contribute more to the property of the enterprise could find themselves pressured, in certain conjunctural situations, to withdraw from the cooperative, taking their “capital” with them, or they might threaten to do so as a means of pressuring others. The power they are not formally granted would reappear and make itself felt in distorted forms, with all the negative dynamics this implies. Thus, it is important that the logic of the model of the workers enterprise proposed here be clearly stated: “one labor share, one vote.”2

Note that a system in which votes are tied to labor shares (say, for elections of a board of directors or for votes in the general member assembly) is only superficially and formally similar to the system of power used in private corporations. The content and essence remain quite different.

In worker cooperative enterprises, ownership of equity and labor are not separated or separable, so these phenomena that characterize the practice of power in capitalist firms are not possible:

- transfers of property through exchanges on capital markets beyond the control of the enterprise (or even unknown to its members);

- processes of concentration of power in the hands of a few some of whom may be owners of minority shares (if ownership is dispersed across many small share holders);

- processes of separation of techno-bureaucratic management bodies which escape all effective control by those with a true interest in management.

The system of governance and power in proportion to the effective contribution made by each member of a workers enterprise offers, then, important structural advantages over the dominant system of private corporations, and over the traditional egalitarian cooperative governance system as well.

With respect to this last point, one of the advantages of this approach – which translates into economic efficiency – is that over time it maintains an equilibrium of influence among the “estates” or classes into which the labor force is divided: workers, administrators, and technicians. Of course, in this system, when the distribution of equity reaches a state of “equilibrium” the engineer and the unskilled worker as individuals have distinctly different amounts of decision-making power. But, if we compare the impact of workers as a group to that of technicians as a group, the two having potentially very different points of view and aspirations, the relative weight of each group notably tends to maintain an equilibrium. Obviously, this is because the quantity of workers is typically greater than that of highly specialized and skilled technicians, which makes up for the different economic valorization of the labor of each category or “estate.”

Let’s take an example: if an enterprise of 100 workers has six technicians whose labor compensation amounts to 25% of the surplus, 12 administrative workers who receive 15%, 40 laborers who receive 35% and 42 unskilled workers whose compensation equals 25% of the overall surplus, those four categories of workers who make up the labor force will participate in the management of the enterprise in the same proportions: 25%, 15%, 35%, and 25% respectively. This would be the “rational power structure” for this enterprise. If, in this same enterprise, an egalitarian principle were established, giving the engineer and the laborer equal decision-making power, we would have a structure in which 6% of the power would go to the high-level technicians, 12% to the administrative workers, 40% to the skilled workers, and 42% to the unskilled workers, a distribution of decision-making power that does not correspond to the effective importance of the different functions of each category. The unavoidable consequence of such an arrangement would be the emergence of a parallel techno-bureaucratic “clique” that exercised real decision-making power, submitting for general voting proposals that in many cases were already adopted and enacted.

Just like the proportional system of participation in surplus, this system guarantees that worker-members with the longest service, and thus the most experience, will have more influence in management. Those with the greatest commitment to the enterprise and its activities, with the most accumulated labor time invested, will have greater decision-making power than new members.

While the egalitarian principle, on the other hand, offers the same formal decision-making power to the founding member and the most recent recruit, it can lead to the formation of cliques of members based on differences in de facto power, for example members with the most seniority, thus impeding the integration of new members in the governance of shared business activities.

Proportional decision-making power not only prevents this severance of formal from informal power, it guarantees both continuity, which is indispensable, and the progressive renewal of leadership groups. It also secures the legitimacy of the Board or Administrative Council. And it does all of this without falling back on practices with dubious cooperative legality (which at times may be necessary in the traditional egalitarian context in order to maintain a minimum of efficiency).

2. The analysis of the problem of decision-making power in workers cooperatives, formulated in terms of strict economic rationality, can end here. Nonetheless, the problem and the solution proposed have profound implications of an ideological and political order that can’t be ignored. The principle, “one member, one vote” has its theoretical roots in representative democracy, a concept whose high moral and political content carries us beyond the sphere of the State and politics, to the terrain of grassroots economic organization. Cooperativism is a project of democratization of economic life, of bridging the chasm between the economic and the political in modern societies that is opened up by the contradiction between the formal recognition of the equality of people before the law and in political life, and the profound inequalities generated by economic life and the relations of production.

We will examine this problematic with some patience and rigor in Section Four of this book (Cooperativism and Democratization of the Market and the State). For now we limit ourselves to underlining the necessity of not confusing the principles of a democratic juridical and political order with the concrete reality of its historical organization and practice.

The election of legitimate authorities, in a process in which the will and choice of each citizen has an identical unit value, is a foundational principle of representative democracy. This principle is based on the belief that all people are citizens with equal rights that are prior and superior to the organization of the State itself.

Nonetheless, the concrete political organization of democratic states is the product of a structure of power in which the authorities selected through an egalitarian vote constitute only one part of a complex system of social power and control. Key to the State’s operation is the bureaucracy (civil and military) whose authority is legitimized not through citizen representation but by the possession of technical competencies, knowledge, and organizational and management efficiency which they mobilize in the exercise of authority and public service.

We can define the modern democratic state, then, as a representative-bureaucratic system of power and control in which the two constitutive parts are supposed to regulate and limit each other in the performance of their respective functions. (Representative-bureaucratic organization, with a different balance of the two elements, is characteristic of practically every modern organization, including political parties, cultural organizations, sports clubs, etc.)

It is important to grasp the reality of representative-bureaucratic organization so as to avoid the mistake of assuming that the principle of the egalitarian vote is in every case the only source of legitimate authority. Nor should it be taken for granted that the duality typical of modern organizational structures is the best, let alone the definitive, solution. The dual nature of the constitutive powers of the State and modern organizations produces a situation of permanent conflict between bureaucracy and representation, the presumed vehicles of technical efficiency and popular will, respectively.

This conflict is sharpened by the spontaneous tendency of the bureaucracy to separate itself and demand, in the name of technical competency and efficiency, an ever greater field in which to exercise its authority, thus contradicting the principle of representation. In parallel fashion, the organizations of citizen representation demonstrate a spontaneous tendency to arouse popular aspirations even when their satisfaction is not always technically possible given the means socially available, thus contradicting the principle of rationality and efficiency. And so, the system of power reveals its dysfunction.

As we noted, the practical application of the representative principle (“one member, one vote”) in the cooperative system, along with other aspects of its traditional organization, have led to the phenomenon of emergent bureaucratization, that is the emergence of leadership groups whose legitimacy is based on the need for organizational efficiency and the presence of people with certain technical competencies (whether real or just asserted). This is a source of dysfunction and conflict that also obfuscates the principle of democratic representation. We will return to this problem later on, but for now let us note that our proposal to create a proportional system of power and management in cooperatives implies that it is possible to overcome dysfunction and conflict by combining democracy and participation in a way that simultaneously meets the criteria of efficiency and representation. In our approach, while everyone participates in “power” or authority in proportion to their work and commitment to the economic organization, operational management is organized as a specialized technical function, always subordinate to legitimate authority.3

3. The relationship between the levels of “power” or governance, on the one hand, and management or administration, on the other, requires further consideration, because even if the difference is theoretically clear, in practice there are numerous combinations and ambiguities.

In effect, the theme of power and the problematic of governance and executive or management authority are intimately related. For example, it is well known that in large enterprises and corporations there is a separation between ownership and administration, a phenomenon that has been attributed to the subdivision of ownership of capital in these firms among thousands of small shareholders. But the separation is due less to the number of shareholders than to the phenomenon of separation and autonomization of capital markets in the larger economy. Shares are traded and circulate in a financial and speculative circuit which goes far beyond the individual firm, in which transfers of ownership of shares have little or no impact on the continuity of business operations.

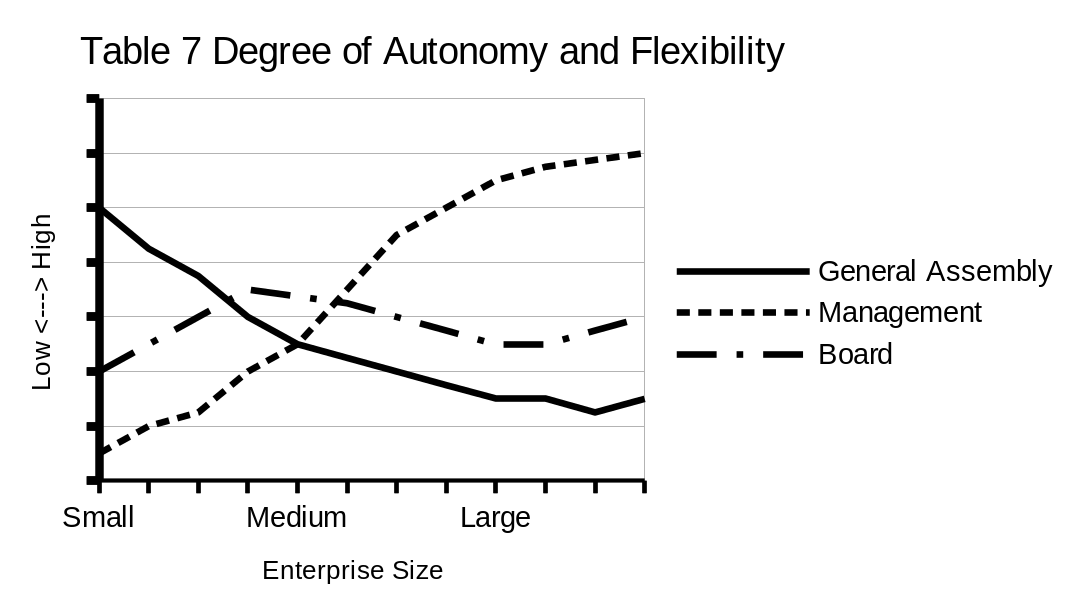

If this were the only cause of the phenomenon of separation, we would not expect to see it in the cooperative sector where ownership of equity is inseparable from work: the shares stay in the hands of the worker-members. Nonetheless, in the practice of traditional cooperativism, especially in the largest cooperative enterprises, it is well known that executive management often operates with autonomy with respect to the governance and representative bodies of the members, as illustrated in Table 7.

This phenomenon is typically explained away on technical grounds: business operations, it is said, require professional administration done on the basis of objective economic and technical criteria, and will suffer if the enterprise is managed in a collective and participatory way that provides ample space for member subjectivity. This is a valid point. It cannot be denied that many cooperatives have opted for a relative autonomization of executive management in pursuit of administrative and economic efficiency. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that this separation has been accentuated in “heterodox” forms of cooperativism developed in an effort to overcome the problem of capitalization and, moreover, by the manifestation of bureaucratic tendencies to which we have referred above.

In the model of cooperative organization that we have proposed, these latter causes of separation are obviated and it becomes possible to devise forms of participatory administration which resolve in a distinct way the need for efficient and objective administrative operations. But in order to resolve the problem one must first understand it correctly, using adequate concepts and avoiding the confusion that arises from the use of ambiguous terms like “decision-making power” (or authority) and “management” (or administration).

In effect, we must distinguish between two different situations in worker enterprises. In the first, there is a separation between “power” or authority (which resides with the organizing category, i.e. the worker members), on the one hand, and the exercise of management and administrative functions (by those who contribute the administrative or management factor, be they members or people hired from outside), on the other. In the second situation, which is quite different, there is no clear separation and to one degree or another, managers take power.

The first situation is normal and can be accepted without major concerns, as long as it is a matter of the worker members not possessing the capacities required to perform that function adequately. The contribution to the enterprise made by the administrators in this case is equivalent to that of any other external factor: technology contributed by specialists, financing obtained through borrowing, etc. As an external factor, it is employed by the organizers of the enterprise to fulfill their objectives and its contribution is duly remunerated. A social division of labor has given rise to a differentiation of factors; this is a positive development to the extent that it implies the perfecting of human (economic) capacities.

Obviously, it is preferable for the factors to belong to the enterprise, and not be external, and in that sense it is normal for workers to want to take possession of this factor and take steps to that end, through member training for management roles or through the incorporation of managers as members of the cooperative enterprise (such that the activity they carry out is seen and valued as one form of labor, treated the same as the other forms). This involves a process of recomposition of social labor which, if said in passing, is one of the profound meanings of economic cooperation and self-management.4

It should be noted that the treatment of this administrative factor presents distinctive features when compared to the other factors, insofar as it is a human factor (a condition shared by the factors labor and community, and, to some extent, technology) and not an objectified factor (like finance and means of production).

As a human factor management relates in complex ways with the other human factors; relations between human economic factors are always also social relations with cultural and political connotations.

Moreover, it is in the nature of management or administration that its exercise involves an organizing and leadership function (in a technical sense) with regards to the operation of all the factors, including labor power. Thus it can happen that those who play a management role place themselves in a hierarchical position with respect to the workers, who are in fact the enterprise’s members and owners. Theoretically, this authority and hierarchy remains limited to a purely technical or operational level, but it is easy to understand that it can generate complex situations, and even give rise to the second of the situations we mentioned above, that is, the assumption of some degree of power by those who exercise the management or administrative function, power that in every way – legally, justly, and in as a matter of economic rationality – belongs to the workers.

In such cases, we can say that the external administrative factor is usurping powers that legitimately belong to the category Labor, which is the organizing category for the enterprise.

4. It may be helpful to refer to a simple schema that distinguishes among the attributes of the different intervening organisms or subjects, based on a certain rationality. The schema takes into account both the need for efficient management (which may require acquiring the factor externally) and the value of a progressive assumption or appropriation of that factor by the organized workers of the enterprise (its organizing category). At the same time, it recognizes that there is a tendency for the administrative function and the exercise of “power” or authority in an enterprise to bleed into each other (an intermixing that is even more accentuated when management is an internal factor exercised by worker members who take on that role).

The systems of leadership (“power” or “authority”) and management that are implemented in an enterprise should correspond to the types of decisions involved and the levels at which they are made. In other words, as the decisions are of different types, made at distinct levels, the mechanisms and forms in which they are adopted can also be expected to be different.

The participation of the labor collective in the adoption of decisions of different types and at different levels is in turn conditioned by the degrees of complexity and objectivity involved in each occasion, it being possible to establish different mechanisms which balance the goals of maximizing participation and optimizing efficiency.

We can divide decisions into two broad categories: strategic economic decisions, related to the enterprise’s “economic organization,” and conjunctural operational decisions, which concern “functions and operations”, the transitory and changing situations that shape daily operations.

We can also distinguish between decisions depending on whether they affect the enterprise as a whole or just one part or section of it. Global decisions refer to the functioning and the dynamics of the whole enterprise, while partial decisions affect only one part of the enterprise, be it a department, section, or subsection. We combine both criteria in the following table.

Strategic planning includes the most important business decisions, decisions affect the whole enterprise in its medium or long term development. It involves the identification of the enterprise’s general and specific political, economic, social, and cultural objectives as well as the ensemble of decisions that make up an integrated and coherent plan utilized by the organization to accomplish those objectives.

Typically, an initial strategic plan is created, then periodically evaluated, revised, and reformulated (usually every year or two). Strategic planning includes:

- analyzing the internal situation and the context in which the enterprise operates,

- setting flexible objectives,

- establishing functional and hierarchical structures and modes of organization for the economic unit,

- determining the economic treatment to be applied to the different factors,

- selecting and designating the people responsible for representing, coordinating, directing and executing the various aspects of the project,

- determining uses of the surplus generated,

- choosing paths of growth, contraction, or productive reconversion, and

- evaluating the degree of fulfillment of the general and specific objectives and of the plans elaborated for the period in question.

Who makes these decisions regarding strategic planning? The organizing category, in this case, Labor, with the proportional participation of all of its members gathered as a General Assembly or a smaller Board.

The General Assembly (or the Board) can form work groups, seek assistance from people with the needed skills, and empower people or specific groups to elaborate plans or propositions, but the decisions must be collective with the direct participation of the members of the enterprise in proportion to the level of commitment that each has made, defined by the units of labor contributed to the cooperative.

In the case of cooperative enterprises organized by the category Community, strategic planning is done by the organizing community itself, in conformity with its particular internal decision-making systems and on the same basis as in a workers enterprise.

The broad participation of the members (worker-members or the laboring community) at this level is indispensable because the marginalization of any sector or group of people, or even worse, the concentration of strategic decisions in a particular group, would imply a true negation of the members’ authority and rights. It would amount to an abandonment of the intrinsic rationality of cooperative ownership, giving rise to a range of negative consequences, including formal or informal conflicts. Moreover, it would degrade the efficiency of decision-making and execution. Broad participation allows for a process of gestation in which the widest range of information from across the collective is considered, resulting in a plan more likely to enjoy the commitment of those responsible for carrying it out in each of its aspects, not out of blind obligation but with free will and with full awareness.

In other words, plans are good when they are actionable and they are actionable when those who put them into practice share the objectives, understand the place and meaning of their actions in the larger group, are personally interested, and adhere of their own volition in the execution of that which has been planned. As strategic plans encompass relatively prolonged periods of time, participation of workers in strategic planning does not imply a kind of permanent “assemblyism” which, by distracting the labor collective from its normal activities and work, would constitute a dysfunctional factor leading to chronic inefficiency.

A second category of strategic decisions, the one we refer to as sectoral policies has to do with the organization of the distinct functional units of the enterprise (departments, sections, teams, areas, etc.) in its medium to long term evolution.

In this range of decision-making, objectives are set and lines of action and the landmarks used to navigate for relatively prolonged periods of time are defined, in accordance with which the viability and appropriateness of direct worker participation in decision-making is determined.

Insofar as it is in the realm of strategic economic decisions it appertains per se to the organizing category. But as it is a question of decisions made locally, in a particular section, the form of participation is not necessarily the General Assembly of all the members. It is in the sovereign power of the General Assembly to delegate this range of decisions.

As we are dealing with local or particular policies that might otherwise require a kind of micromanagement on the part of the General Assembly, the participation of the workers or the community (depending on the organizing category involved) can normally be accomplished through local bodies like committees or working groups, formed by the members of a relevant functional subgroup, or by sectoral committees or teams if it is a matter of larger subgroups, which would include the corresponding working groups.

At the same time, it is necessary that sectoral policies in each department or section be harmoniously and functionally integrated with those other subgroups and with the enterprise as a whole, something that the individual working groups or committees can not accomplish by themselves. In that case, the General Assembly can delegate to an Administrative Council or an elected Steering Committee those decisions which are strategic but nonetheless pertain to specific functional units of the enterprise. This body can best take on the responsibility for coordinating decisions about sectoral policy for the functional subgroups.

One way to combine the exigencies of grassroots participation with the need for integration and articulation of the various sectors, which is a distinctive characteristic of this realm of sectoral policies consists of organizing an Administrative Council and Steering Committee in which one representative from each subgroup participates, in addition to at large members designated by the General Assembly.5

Another promising approach would be to delegate to the Sector Committees or Working Groups the elaboration of proposals relevant to their specific fields of action, to be studied, improved technically, and finally adopted as resolutions by the Administrative Council or Board.

We now move to the level of operational decisions made in the course of an enterprise’s daily operations. In this realm it is logical and appropriate that the responsibilities fall to the management factor. The question is how best can the enterprise achieve its operational objectives?

We use the term executive administration for the realm of business decisions pertaining to the functional and conjunctural operations of the entire enterprise, the daily application and concrete implementation of the strategic plans of the enterprise. Here we find the organization of the mechanisms, programs, and procedures of production, marketing, quality control, etc. and the decisions the enterprise constantly makes as it adapts, reacts, and responds to changing conditions that present themselves in the market and within the enterprise itself.

It is characteristic of this realm that the decisions to be made are often of a technical character and must be made and enacted rapidly. For this reason it makes sense to have decisions made by people with adequate professional and economic training as well as experience in business management and administration. It also makes sense that these responsibilities be concentrated to some extent in a small group of people. All of this suggests the need for a hierarchically structured executive leadership body, normally in the form of a General or Executive Director and chiefs or coordinators from each sector or department.

It is the responsibility of the organizing category, the same subject that assembles and controls all the necessary factors of production (workers or community), to select the right people for this administrative function. In order to assure that the people chosen are suited to their roles, it may be wise to have them be selected by the Administrative Council, especially in an enterprise with a large membership. Nonetheless, while the technically efficient and professional execution of these functions is necessary, it is no less important that the members of the executive administration act in conformity with true cooperative values, methods, and approaches, and that workers maintain mutual trust and fluid, conflict free, communication. To guarantee this and at the same time impede the emergence of any bureaucratic separation of management cadres from the labor collective, the General Assembly should establish the criteria and requirements that the Administrative Council applies when selecting executives for the enterprise. In some cases it might be best for the collective itself, united in a General Assembly, to ratify or veto the executives selected.

Finally we come to the fourth realm of decision-making: local operations. This is a realm of conjunctural decisions about daily operations in particular sections or departments. These are decisions about organization of labor in each of the sections or parts into which the enterprise is divided as well as the infinity of situations and problems that present themselves with regard to the production process, marketing and sales, process, etc.

Here, too, technical competence is key, to fulfill this function the enterprise needs people who possess and can contribute the economic factor management. As such, decision-making responsibility falls on those who have the required competencies.

Nonetheless, taking into account the need for the organizing category (workers or community, depending on the type of enterprise) to take possession of and appropriate this factor, and given the greater simplicity of the decisions involved, this is a field of decision-making in which the process of “recomposition of social labor” can be initiated with fewer difficulties and with particular benefits. In other words in this realm it is extremely beneficial to have the active participation of the workers in the making of decisions.

This being the field of immediate action in which the workers are permanently engaged, the structure of a system of group and participatory management seems appropriate, superior in any case to standard authoritarian processes, since the people who are best situated to decide are always those who are are in direct contact with, and have a personal interest in, the object at hand and the results of the decision. Moreover, this corresponds to the community and social values of cooperativism itself, in addition to being an expression of the unity between conception and execution that characterizes labor that is truly human.

Being a question of small groups, the formation of consensus and the elaboration of the decisions adequate to each circumstance doesn’t imply slow and cumbersome procedures, and the practice of permanent participation itself tends to facilitate the decision-making process in a context of fraternal human relations. It would be good in any case to establish a decision-making procedure that involves the constitution of working groups or teams in each section or workplace in which unitary operations are carried out (thus having a functional and thematic unity), those teams being directed by a worker in coordination with the working group. These same committees or working groups can come to be an important instrument of information and communication with the higher organizing levels in view of a greater integration of the members of the enterprise as a whole, preventing the process of separation of between leaders and led that we discussed earlier.

Up to now, we have spoken of the right of worker members to participate in the management of the enterprise and the need to make such participation real. But workers are not always disposed to participate effectively in activities which imply sacrifice of time, mental effort, labor and the taking on of responsibilities.

Naturally, participation provides its own benefits and satisfaction to whose who participate, creating opportunities for personal development and advancement in the enterprise. It permits people to have influence in the enterprise and to ensure its alignment with their won objectives and interests. Nonetheless, such possibilities, benefits, and satisfaction are not always sufficient for assuring active, constant, and committed member participation.

For this reason, in some cases it can be convenient to establish economic incentives to foment and enhance worker participation in decisions on the appropriate levels. The forms, procedures, and criteria for assignment of these incentives or benefits can take many forms, but it is important to understand, in principle, that they are legitimate, and can be established in perfect harmony with the general criterion of pro rata or patronage distribution.

In effect, management is a factor that members contribute to the enterprise like any other economic factor, having a productivity that can (and should) be recognized. The incentives for participation that are established can be understood as a legitimate mode of remunerating the contribution of a necessary economic factor.

In worker enterprises, when management (or parts or aspects of it) is carried out by the workers themselves, and thus assumed by the organizing category, it is constituted as an expression of labor: in fact it too is labor.

Its remuneration nonetheless presents certain complexities with regards to quantification and valuation. It may not be entirely possible to measure on the basis of time spent (hours, days, etc.) due to the importance of management’s qualitative elements. This it why it may be useful for incentives to be established in some direct relation with increments of productivity or profitability associated with the decisions that are adopted. There is no formula, this theme must be examined in each enterprise and with reference to its particular procedures, organization, and circumstances.

Translated by Matt Noyes

Header image by Jeff Warren and Caroline Woolard. CC BY-SA 3.0

- 1Having posed the question in these broad terms, the analysis we present in this chapter refers especially to enterprises organized by the category Labor; with some reference to Community enterprises as well. The criteria and analysis that we explain here can not be applied indiscriminately to other types of cooperatives and other forms of associationism which also form part of the cooperative phenomenon, and in many of which the principle “one member, one vote” remains sufficient.

- 2An apparent deviation from the second of the International Cooperative Alliance principles, Democratic Member Control, which reads, “Cooperatives are democratic organisations controlled by their members, who actively participate in setting their policies and making decisions. Men and women serving as elected representatives are accountable to the membership. In primary cooperatives members have equal voting rights (one member, one vote) and cooperatives at other levels are also organised in a democratic manner.” - MN

- 3It is important not to extrapolate from this with reference to the general theme of governmental and political organization.

- 4Similarly, Arizmendiarrieta stressed the importance of “socializing knowledge in order to democratize power.” (Reflections, #185. José María Arizmendiarrieta. Solidarity Hall. 2022.) - MN

- 5This resembles the integrated circles structure of Sociocracy. See https://www.sociocracyforall.org/ - MN

Citations

Luis Razeto Migliaro, Matt Noyes (2023). Cooperative Enterprise and Market Economy: Chapter 7. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/articles/cooperative-enterprise-and-market-economy-chapter-7

Add new comment