Introduction & Preface | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 9 | Chapter 10 | Chapter 11 | Chapter 12 | Chapter 13 |

Translator’s note:

How much should a new worker have to contribute to the cooperative? How much money should they be able to take with them when they leave? How should their shares in the cooperative’s equity be valued? How should the cooperative set pay rates? Should members be paid a uniform rate based on the hours they have worked, or should their contributions be weighted to reflect different levels of skill and experience? Should they be compensated for types of labor not valued in the market, such as care work? Should worker cooperatives employ non-member workers?

In this chapter, Luis Razeto Migliaro further fleshes out the economic theory of the cooperative enterprise, tackling problems that are at once conceptual and practical, and offering solutions that often differ from traditional cooperative approaches. Perhaps the most provocative point is the argument that technicians and managers deserve a greater portion of the surplus because in their work they contribute not just labor power but also the factors of technology and administration they have acquired through study and/or experience.

Razeto also opens the door to distributing surplus not only on the basis of labor as conventionally understood and valued on the market but also for the work members do to build solidarity and integration, the “C factor” that is so important to cooperatives. The Distributed Cooperative Organizations, or DisCOs, can find here an additional analytical basis for their feminist economic practice: tracking and remunerating not just “livelihood” work but also “care,” and “love (pro bono)” work.

- Matt Noyes

Chapter 6

Labor relations and the admission and withdrawal of members in the cooperative enterprise.

1. The social base of the small self-managed enterprise is a group of workers who come together with the specific aim of carrying out the functions necessary for the operation of an enterprise: production, administration, marketing, etc. We are not dealing with a natural group – as in a family-run micro-enterprise – nor a community of people – as in a community enterprise, in which people come together on the basis of location, ideological, cultural, or religious orientation, a similar social condition, or a shared need for subsistence. In such cases, what unifies members is a shared situation or motivation that is not directly tied to the functions that need to be carried out in the economic unit. The workers who form a small self-managed enterprise, on the other hand, come together as workers, each contributing their portion of the labor power, skills, and management capacities previously identified as necessary for the enterprise.

Put another way, in a small self-managed enterprise a human group is formed on the basis of technical and functional criteria. It is not enough, though, for workers to have the technical capacity needed. They also need to have a certain understanding of, and commitment to, the idea of self-management and cooperative work.

The formation of the human group in a self-managed enterprise is, then, a complex process that implies formal and informal (but efficient) selection procedures to ensure that the collective of workers formed is both technically integrated, and culturally prepared for self-management.

From this theme we can trace various lines of inquiry since it involves aspects that are psychological, social, cultural, economic, and also political. Our focus here is on the economic dimension – in the broad sense – starting with the controversial problem of the admission and withdrawal of members.

Worker self-managed enterprises offer their members a permanent solution to the problem of labor. Because members make contributions of financial, material, administrative, and technological resources, in addition to their labor, their participation can be expected to be highly stable. Nonetheless, the question of withdrawal and admission of members is crucial.

As it grows, an enterprise needs not only additional capital but also more labor power. The most obvious way to increase labor power is to add new workers, that is, new members. The incorporation of these members implies not only an increase in the number of workers but also quantitative and qualitative changes in the other human factors they contribute. This has an impact on management (the administrative factor), internal human relations (the C factor), and the complex of information, skills, and competencies that constitute “the way things are done” in the enterprise (the technological factor).

For all these reasons, the problem of admission of new members requires patient analysis. We are opening up a theoretical problematic of the greatest importance, with respect to which cooperatives have traditionally lacked transparency. While in theory there is an established principal of “open doors,” in practice the principle has been difficult to follow due to the fairly obvious challenges posed by its strict application.1

In fact, in traditional cooperatives the recruitment and admission of new members typically poses a big problem, in response to which they impose severe limitations. This is related to two elements: the way ownership of equity has been structured, and the terms and conditions of labor. As we will see, posing the question of ownership in a way that is economically rational for the cooperative enterprise helps us solve the problem of admission and integration of new members, as well as that of withdrawal, another complex and confusing aspect of traditional cooperativism.

When a workers enterprise “capitalizes” its gains, growing by reinvesting a portion of the surplus in the enterprise, part of the value of the labor carried out by its members is transformed into equity. If that equity is treated as social, with workers sharing equally in its ownership, the admission of a new member (expanding the cooperative, for example, from twenty people to twenty one) would amount to an automatic transfer of property – of accumulated work – from the twenty members to the newly admitted member. The twenty existing members would lose 5% of the value they had accumulated and placed in common. This is obviously unjust and, economically speaking, irrational. Yet this is what often happens in cooperatives which accumulate capital through one of the opaque processes we mentioned earlier. Only those cooperatives which have no internal growth but simply add members are immune to this problem.

As a logical consequence of this approach, as cooperatives grow and accumulate “capital” they tend to place rigorous and strict conditions on the admission of new members, when they don’t resist adding members altogether. It would be normal, in this situation, to require new members to make a capital contribution equal to that made by the existing members, and thus enter on an equal footing. A worker who wished to become a member of the cooperative would then have to make a larger investment than the existing members did when they joined, and the amount required of new members would grow as the cooperative grows. Moreover, new workers would have to be prepared to make this contribution without being able to withdraw their invested money at a later date.

It should be clear that this inflexible approach to labor is irrational in simple terms of economic efficiency. Moreover, it is discriminatory and in open contradiction with the cooperative principle of open admission.

The economic rationality of the cooperative enterprise of the type we have theorized offers a transparent and just model that resolves the question of admission of new members without implying any transfer or loss of accumulated value on the part of the existing members.

It would just be a matter of incorporating new worker members with the requirement that, in addition to having the characteristics suited to the nature of the work involved, they make the same initial capital contribution as all members, measured in units of simple labor. Nothing prevents the new member from making a larger financial contribution that equals or even exceeds the accumulated shares of existing members. Whatever contributions the new member made would be recorded in labor shares in their name, under the same conditions as the labor shares issued to others, with the same rights and obligations. It should be noted that if the new member contributed money, in no case would they be contributing to the equity of the enterprise on a different basis than the other members, because once contributed to the cooperative the money would be treated the same as other contributions and subsumed into the Labor category. It would come from a similar source as the contributions initially made by other members, and thus, would count as a quantity of value previously accumulated and owned by the individual member.

What would motivate an aspiring member to seek admission? Along with the possibility of putting their labor power to use in an enterprise that belongs to them, they might be motivated by the opportunity to make productive, effective, and efficient use of their savings. As a member of the organization with the same rights as other members, they could administer their own labor power and savings. They might also be motivated by the benefits and opportunities that the enterprise offers its members, including participation in a social movement that is multifaceted – economic, social, and cultural – and offers the possibility of entry into the market on the basis of a higher personalist and comunitarian ethics.2

2. It should also be possible for members to leave the association, following a procedure that is consistent with these criteria of admission. In concrete terms, this implies recognizing and guaranteeing to the each member the right to withdraw their own accumulated Labor when they leave the enterprise, a right that refers not only to any personal monetary deposits they have made but the share of the global equity of the enterprise to which they are entitled.

The accumulated Labor in question is that part of the equity made up of what we have termed “personal objective factors,” with respect to which labor shares have been assigned to each member. As for the “human” factors, being indissolubly attached to the person of the worker who contributes them, obviously workers take those with them when they leave the enterprise.

So, the member who withdraws has a right to receive that part of the enterprise’s equity represented by the shares they possess. Take, for example, a worker who, at the time of withdrawal, has a total of 1,000 labor shares, equivalent to 1,000 days of simple labor. The question that arises is how much are their shares “worth” at the moment of their withdrawal? This is important to the enterprise since it determines how much equity will be lost when the member leaves.

The 1,000 shares in our example have been accumulated over several years, which means that, in accordance with year by year variations in the enterprise’s productivity, the monetary equivalents they represented were different. How do these different monetary equivalents affect the final calculation of share values at the moment of withdrawal?

The consideration of monetary equivalents of the shares issued leads us first of all to rule out the idea that the withdrawing member should receive the current value of the day of simple labor for their shares (i.e., the value as of the last financial statement, or at the end of the fiscal year during which they withdraw). If member shares were valued this way, the distortion would be obvious: an especially profitable fiscal year would result in day of simple labor with a high monetary equivalent. If all the labor shares were made equal to this value the total value of accumulated shares would exceed the objective equity of the enterprise. In such conditions, members would have an incentive to withdraw from the enterprise when profits were high, taking with them a proportionally larger part of the equity. On the other hand, if the year in question were especially bad, a withdrawing member would receive a smaller portion than they were due. Worse still, if the enterprise lost money during that year, the member would end up having to pay the equivalent of their shares multiplied by the value of losses, measured in days of labor.3

We have to look elsewhere for a rational solution to this problem. The total shares issued correspond to the current value of the objectified equity, so the percentage of shares owned by the withdrawing member correspond to the same percentage of the current value of equity. It is necessary, then, to take the updated value of the objectified equity and divide it by the total number of shares issued, the result being the current value of the shares owned by each member (including the member who is withdrawing). But how to determine the current value of the objectified equity?

The monetary equivalent of goods of any type is not determinate except insofar as they are exchanged on the market. The price of a commodity is, in effect, the result of an implicit or explicit negotiation between two parties – the seller and the buyer – and depends on multiple factors and elements, some relative to the commodity itself and others to the conjunctural conditions of the market. Thus, it is especially difficult to determine the current value of an enterprise if it isn’t for sale. The usual method used to estimate the value of a good before it is exchanged consists of carrying out an appraisal, which should technically be done by a third party who is neither the owner nor the potential buyer, nor any other interested party (which in our case would include the departing member as well as those who remain). The cost of the external appraisal can be reasonably charged to the departing member whose withdrawal makes the appraisal necessary.

Now, if the enterprise has operated continuously for some time, strictly adhering to the criteria indicated with respect to the issuance of shares, and has maintained adequate accounts, an outside institution should not be necessary. The enterprise’s own accounts should provide the information needed at any moment. This will become clearer if we take time to consider the character and the mechanisms of the labor share system.

3. The first thing we need to establish is that labor shares differ from shares in a capitalist business in a fundamental and decisive way: they cannot be transferred or traded on the market. They do not have a commercial value and are not subject to conjunctural variations in value. (At the most, there could occur some trading of shares among members, which we do not encourage for fairly obvious reasons. It is also possible to have some intermediation of the shares in a special system of intermediation of cooperative assets, as we will propose further on when examining the possibilities of functional integration of the cooperative sector.4)

In addition to their nominal or face value, expressed in units of labor, which doesn’t change because each share is the equivalent of a day of simple labor, labor shares have two other values expressed in monetary units: “registered value” and “book value.” The registered value of labor shares is their monetary equivalent at the time of issuance, whether they were issued when the enterprise began or at the end of a given fiscal year. Shares issued at different points in time will have different registered values, but the registered value of a share does not change over time.5 Book value, on the other hand, is variable, and should be established at the end of each fiscal year for all shares issued (not just those issued in that fiscal year). Book value represents the current value of the objectified equity of the enterprise (the value of the total assets minus short-term liabilities), divided by the number of shares issued. The resulting number, the book value of each labor share, is the monetary equivalent of the day of simple labor in this enterprise taking into account its operations over the course of its existence. Book value tells us, then, the average value of the day of simple labor in that enterprise. This information is found on the enterprise’s annual balance sheet, which provides the updated monetary value of the enterprise’s objectified equity, taking into account the depreciation and valorization of corresponding assets.

So, which of the monetary values of the shares – registered or book – should be taken as the basis for estimating the value of the shares held by the member who withdraws from the enterprise? We say it is the book value, but to understand why, one needs to consider how the various values differ and the affect of applying one or the other.

We said that the book value (or unit average value) of the labor shares can vary with each fiscal year. What is the basis of these variations? What determines them? Obviously, they depend on the profitability of the enterprise but not just that of the given fiscal year. The book value of an enterprise is an average of its annual profitability over the course of its existence; a rise or fall in profitability in a given year is a variation with respect to the previous book values. There is a strict relationship, then, between the registered value of the shares issued and the book value of the enterprise. Interestingly, it turns out that the book value of the total shares is equal to the sum of registered values of the shares issued, if these values are monetarily corrected in order to compensate for the devalorization of money, or, more exactly, to recognize changes in the market valuation of the enterprise’s own assets.

This fact reveals the transparency of the value of labor shares in workers enterprises and the substantial difference between labor shares in a cooperative and shares of capital in capitalist corporations. Variations in the average or book value of labor shares have nothing in common with the fluctuations that shares of stock undergo in corporations, in which the nominal value of shares maintains little relation with their book value and virtually no relation with their market value, giving rise to the familiar phenomena of speculation.

In a workers enterprise the book value of shares does not vary with the growth of the equity of the enterprise; in effect when the equity grows and the enterprise’s “capital” accumulates, the value of the new equity is automatically expressed in the issuance of new labor shares.

That’s not how it works in capitalist enterprises where the process of internal capitalization (reinvestment of profits) does not always result in the issuance of new shares. In fact, it normally results in an increase in the book value of the existing shares. New shares are generally issued as a means of acquiring new capital on the market.

The wear and tear and loss of value of machinery as it is used does not signify a gradual loss of value of the equity represented by the shares. That loss of value is accounted for in the assets on the profit/loss statement, discounted – if we may use the term here – from the gains made in the given fiscal year. Reinvestment in machinery does not lead to the issuance of new shares, since it has the effect, simply, of preserving the value of the shares previously issued.

But the most interesting thing we observe is that in the book value of the labor shares we see reflected not only increases in the equity of the enterprise but also and in a special manner, changes in its profitability. In effect, the registered value of the shares issued each year depends directly on the sum of the profits generated during that fiscal year; while the number of shares issued depends on the percentage of the overall surplus that is directed to increasing the equity.

So, if one year of 10,000 days of labor generated a surplus of $10 million, each share would have a value of $1,000; if 20% of the surplus were capitalized, i.e., $2 million, 2,000 shares would be issued and distributed.

If, the following year, 10,800 days of labor generated $9 million, each share issued would be the equivalent of only $833; if 15% of that surplus were capitalized, that is $1,350,000, 1,650 shares would be issued.

As the shares issued in the following year have a lower registered value than those issued in the previous year ($833 compared to $1,000), the unit book value of the shares issued in both years would fall in relation to their book value in the previous year. Thus:

Year One

Increase in equity….. $2,000,000

Number of shares issued….. 2,000

Registered value of each share….. $1,000

Year Two

Increase in equity….. $1,350,000

Number of shares issued….. 1,620

Registered value of each share….. $833.3

Results

Increase in equity over two years….. $3,350,000

Total shares issued (both years)….. 3,620

Average or book value of the shares….. 3,350,000 / 3,620 = 925.4

Sum of registered values of shares issued in two years….. (2,000 x $1,000) + (1, 620 x $833.3) = $3,350,000

It can happen, then, that the same quantity of money invested in the enterprise gives rise to the issuance of many shares of low unit (registered) value, which happens if the enterprise has been less profitable, or the issuance of a few shares of high unit value, if the profit has been high.

In both situations the overall sum of the equity will not be affected, since in both cases the increase will be the same, that is, proportional to the amount invested.

Nor will the different situations affect the total amount of equity belonging to each member. In one case, members will receive a greater number of shares of lesser unit value, in the other, fewer shares of higher value. Remember that the quantity of shares held by each member represents the quantity of days of simple labor, the profits on which have been re-invested in the enterprise.

The difference does show up, however, in the book or average value of shares in the enterprise, which members can use to gauge the performance of their enterprise, tracking its rising or falling profitability over time. Executives of capitalist corporations have to seek this information in the market, or in stock exchanges, relying on unstable and dubious signals based on the subjective predictions of profitability and future market conditions made by external agents. Members of the cooperative have direct knowledge of both the sum of labor accumulated in their enterprise and its historical profitability, and make investment decisions on that basis. The advantages of this transparency are obvious.

Now, from the previous example it is easily understood that when determining the amount of money due to the member who withdraws from the cooperative, book value and registered value lead to different results. Let us suppose that the member possesses 100 shares with a registered value of $1,000 and 40 shares worth $833.30. If we measure the member’s portion of equity by the registered value of their shares (assuming no monetary devaluation) they would be due $133,332 = (100 x $1,000) + (40 x $833.30). If we measure their share by the book value of their shares the member would be due 140 x $925.40 = $129,556. The difference is owing to the fact that the member’s participation in the surplus was not the same in both years. In the first year they were allocated 5% of the shares and in the second, only 2.47%. With respect to the total sum of shares, at the time of withdrawal the member owned 3.87%. This is the percentage of the current value of the equity the member should receive on withdrawal.

The justification for this resides in an essential fact: equity is the total sum of labor accumulated in the enterprise, which corresponds to and is expressed as a total sum of units of simple labor. The fact that this sum was sold and resulted in different annual rates of profit doesn’t change this essential fact. If, on the contrary, one were to measure the equity by the registered values it would amount to adopting money as the standard of measurement instead of labor. This would lead to serious consequences for the enterprise as it would give rise to speculative phenomena. For example, members who recently joined the cooperative, at a time when profitability was high (based in all likelihood on sacrifices made in previous years by older members), would leave the enterprise with large gains, the cost of which would be paid by the members remaining in the cooperative.

4. Having clarified the criterion and the mode of measurement of the portion of equity that a member is entitled to take with them when they leave the cooperative, we now need to determine the means by which the enterprise will reduce the equity in that amount. The right to recuperate one’s share of the equity when withdrawing must be regulated in such a way that the normal functioning of the collective business activity is not disrupted when one or more members leave the cooperative.

If the withdrawal of a member – whether due to retirement, expulsion, or voluntary withdrawal – were to imply the automatic deduction, in money, of the total amount of their accumulated contributions, the enterprise would find itself facing very serious financial and operational difficulty. To avoid this it is important to have clear bylaws provisions that define the norms and procedures needed protect the enterprise.

For example, the enterprise might require members to give one month’s notice before withdrawing from the cooperative, or adopt a policy of paying out the member’s equity share after a certain period of time (e.g., six months), or progressively (e.g. in quarterly three-month installments, or a certain percentage per month). Some cooperatives require a member who wishes to withdraw to find a replacement who will pay the equivalent of the withdrawing member’s portion of the equity, a practice we believe is unwise because the process of joining the cooperative should not be based on criteria defined by those who are leaving. If the norm were such that the selection of the replacement member were made by the organization, it would alleviate but not eliminate these problems, for example by making it too difficult for members to leave the cooperative, a clear contradiction of their basic rights as members.

An alternative, but more complex, approach would be for the cooperative to pay off the departing member’s accumulated days of labor as if it were a case of external financing, a loan made to the cooperative in the usual terms offered on the market. The most simple way to do this would be to issue notes or debt instruments in the amount of the member’s share in the equity, which the cooperative would pay off from its reserve funds the same way that any enterprise pays off its debts.

Later, when we discuss the functioning of an integrated economic subsystem of cooperatives and worker enterprises, we will see that it is possible to establish a kind of “values market” and a cooperative financial entity in which labor shares and debts can be invested and guaranteed.

Whatever procedure one establishes, the withdrawal of a member – just like the admission of a new member – poses the question of how to recalculate the percentages of ownership of the remaining members, on the basis of the new total resulting from the payment of the shares due to the withdrawing member, or the addition of shares, in the case of a new member.

Note that the withdrawal of accumulated “capital” by the withdrawing worker is not some kind of concession to capitalism but an obligation derived from the internal logic of cooperativism, indispensable for ongoing transparency of its social relations.

If the member did not withdraw their “capital” upon ceasing to work, and thus retained ownership, they would become a non-worker member, which would open the door to a growing separation between capital and labor. Non-worker members could propose or demand that governing bodies make decisions that go against the interests of the worker members, for example, that the proportion of surplus dedicated to remuneration of “capital” and the proportion of profits distributed in money be greater (or lesser) than that which the workers desire. They might demand increases in production or intensity of labor so as to obtain greater profits, which resembles the worst aspects of capitalism. All of this flowing from the introduction of a duality of interests in the governing body.

A similar problem, but in the opposite direction, arises when worker enterprises hire labor power in the external labor market without providing those workers a way to become members of the cooperative. Here too we see a separation of capital from labor which generates economic distortions that are both harmful and ethically questionable.

The presence of wage laborers and other non-member workers implies the introduction into the cooperative economy of a phenomenon analogous to speculation in the capitalist economy (a phenomenon born of the external contracting of non-productive capital).

In effect, if one part of labor is counted among the costs of production, as an external economic factor contracted by the organizing category of the enterprise – which in the case of a worker enterprise is also Labor – the essential economic objective of the enterprise will be immediately obscured. This is because, as we saw, the economic objective of a worker enterprise can be no other than the maximization of the value of Labor. It will be in the interests of the worker members who organize the enterprise to pay the hired workers as little as possible, since that will increase the profits, that is, the value of the labor they own.

In such a case, what would be the measure of the self-exploitation and hetero-exploitation of labor? We would have a situation in which the member of the cooperative would operate as both capitalist and worker, with parallel and contradictory objectives. Not only would this generate economic inefficiencies, it would introduce a principle of conflict between workers which could lead to the dissolution of the enterprise.6 If it is difficult to accept the exploitation of labor by another economic category, e.g. Capital, how much more unacceptable is it to see a worker or group of workers deliver part of the value they create to other workers, the same as them, who do the same work at their sides?

(Note that the speculative phenomenon arises whenever the organizing category of the enterprise contracts a proportion of the same factor on which it is based, that is, when an economic category establishes relations of exchange with itself. The case of financial speculation is well known: money that grows in value by diminishing the value of the money of others. Something similar happens in a consumer cooperative, when it sells its products both to member and non-member consumers. On one side, consumer members optimize their benefit by reducing prices as much as possible, on the other, the same members profit from selling to non-members at high prices. As it is not possible to have two sets of prices in the same store, one for members and another for non-members, consumer cooperatives that also sell to non-members end up selling at relatively high prices.7)

In practice, cooperatives have at times had to turn to hiring non-member workers. This is largely a consequence of a lack of transparency with regards to equity and the form of property, which, as we have seen, generates obstacles to the admission of new members even when their labor is desperately needed. This problem disappears when the cooperative economic logic functions coherently, and rational mechanisms for the admission and withdrawal of members are established.

It should nonetheless be recognized that a real problem remains: in order to take advantage of favorable conjunctures, the enterprise may find itself required to temporarily increase its labor force without being able to guarantee continuity of employment. Admitting new workers as members in this situation could give rise to future imbalances. We shall see later on that this relative inflexibility with regard to the labor factor can find a rational and efficient solution in an economically integrated cooperative sector, through the implementation of an intercooperative “labor exchange.”

In any case, some flexibility can be allowed in a worker cooperative as long as it does not turn into a habitual practice. For example, it may be indispensable to make use of external labor to meet certain temporary labor needs, for example to replace a sick worker, fulfill an order in a short time, or perform a function that worker members are not able to do, etc. In such cases it is acceptable for the enterprise to hire external workers, being sure to pay them justly, not seeking in any way to enrich the cooperative and its members at the hired employees’ expense (i.e., paying the external workers the full value of what they contribute to the enterprise) and seeking to reduce the duration of this anomalous situation. If it is not possible to limit the duration, the cooperative must seek a way to incorporate the worker as a member or to effect the transfer of skills or special knowledge to an existing member.8

The last point leads us to other aspects related to the process of recruiting and onboarding new members. In reality, just as the withdrawal of members requires some formal mechanisms to reduce the problems withdrawals can imply for the enterprise, the addition of new members needs to be carried out according to careful procedures.

New members must be recruited in response to functional needs of the enterprise, as technically evaluated. In the selection of applicants it is wise to apply the same requirements that were established for the members of the initial group (unless the group has explicitly changed those requirements for solid reasons) such that the group maintains homogeneity. The addition of a worker implies their onboarding as a member: a new member should know and adhere to the objectives of the enterprise and its mode of organization and operations, and be aware of their rights and duties.

For these reasons it makes sense to establish a probation period of no more than six months (to avoid legitimation of the use of wage labor) with a clear agreement that at the end of the probationary period the cooperative will make a definitive decision as to whether to offer the worker membership in the cooperative. If the worker declines to join, they have to leave the job.

When a new worker joins a workers enterprise, they contribute not only labor power, but various other productive factors: financial (beyond the initial membership dues)9, technological, and administrative factors, as well as the “C factor” (solidarity). Given their multiple contributions, their participation in the equity of the enterprise and the distribution of surplus needs to be specified, which implies a revision of the percentage of equity owned by each of the existing members. Obviously, this needs to be done whenever a new member joins (or withdraws), though it makes sense, when creating a position, for the cooperative to make a provisional calculation of their contributions before recruits even begin the probationary period.

The way this is done is simple: labor shares are calculated based on contributions to equity, and contributions of labor power are evaluated according to the enterprise’s current system of qualifications.

5. – In the previous chapter we left unexamined the extremely important question of how to measure the differential participation of direct labor (of internal human factors) in the creation of the product. It is now time to take up this point.

We saw, in general, that members’ labor is not remunerated in fixed quantities, like a monthly or bi-weekly salary; rather workers receive anticipatory distributions of surplus. That is, they receive one part of the surplus directly, in money. If a portion of the surplus is allocated to investment or reserves, the distribution takes the form of labor shares.

The most important question is how to determine the amount of surplus that should go to each worker for the work they have done for the enterprise. The correct criterion is to remunerate workers in accordance with their productivity, that is, the contribution their labor makes to the generation of surplus. This means it is necessary to recognize the value of the different types of work they do. Now, we know that each worker works a different number of hours in a day or a month and that the work they do and the functions they perform are not the same, nor are they equally productive. The problem, then, is to determine the correct amount to allocate to each worker, taking into account both quantitative and qualitative differences.

The first step is to establish a scale or rate for each type of work. This can be done in two ways.

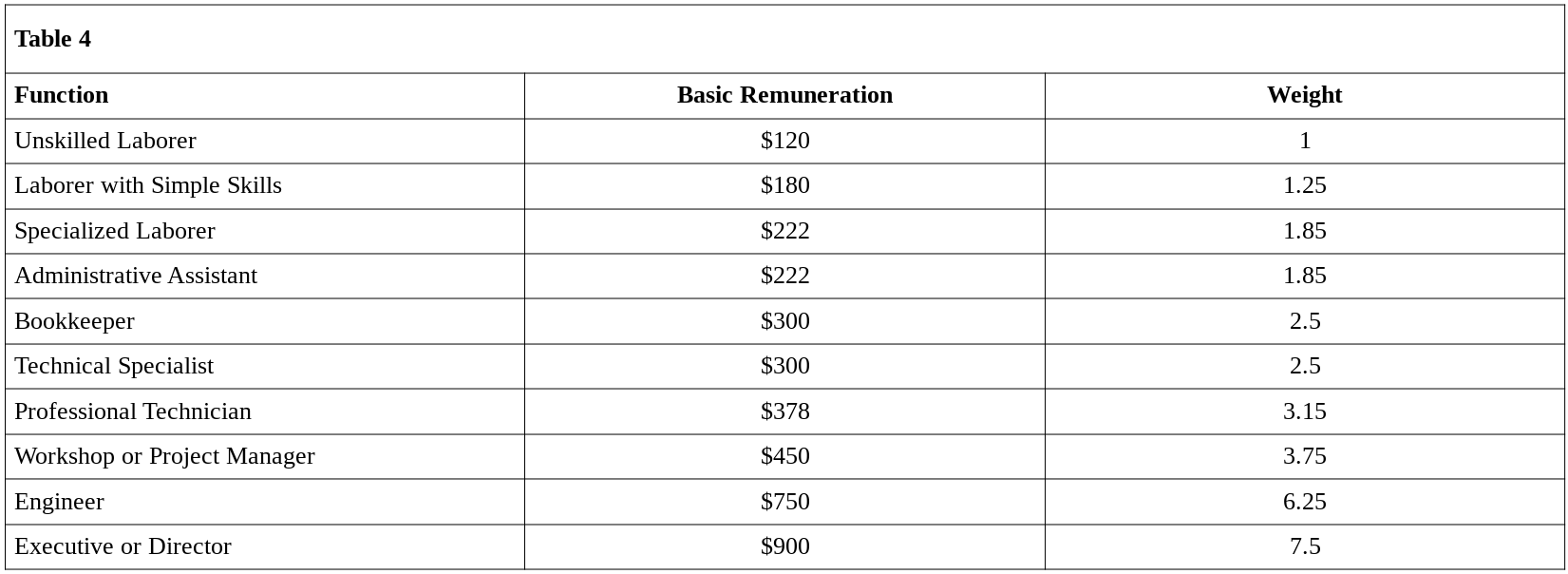

The first is based on standards and indices provided by the market, in a form analogous to the way we measured members’ contributions of objective factors in the previous chapter. Because human factors, too, are constantly being valued in the market, the workers’ enterprise can use opportunity costs to determine the value of internal factors that workers contribute directly and personally. That is, we can use as a standard the amounts that workers could get paid on the market to do what they do in the cooperative, income that they sacrifice in favor of remuneration from their cooperative. We do this not to define fixed amounts to be paid for labor power but to establish a scale of weights to be applied when allocating surplus. Opportunity cost is measured in a given moment, when the enterprise begins operations. Of course, the costs are subject to change and can be adjusted later. But it is always a question of dealing with weights since workers who organize enterprises receive distributions of surplus and not a fixed salary. What are these weights based on? What is the unit of measurement? Clearly, we can use the same approach as when we defined units of simple labor. If, for example, the market rate for a day of simple labor is $500, and for a specialist it is $1,250, we will give the days worked by the technical specialist a weight of 2.5 – the number of days of simple labor that they contribute in one day of work.

A second way to measure the direct contributions made by workers in their daily work is based not on the market but on criteria developed autonomously by the enterprise and the cooperative sector as such. For example, it is possible to devise a specific criterion for the cooperative sector based on an assessment of tasks and functions, carried out in a participatory manner, that would establish levels and corresponding scales of remuneration, with appropriate technical criteria. In the process one could establish the value of contributions that the market habitually ignores (for example contributions workers make to the social integration of the group, that is, “C factor” contributions, which are undoubtedly of great importance and value in this type of enterprise), and establish criteria that are qualitatively distinct.10

In the absence of carefully studied and field-tested systems, the adoption of market standards offers approximations and indicators that are usually relatively sound. To understand this point and, at the same time, identify possible criteria for the formulation of an internal system of evaluation of personnel, one must keep in mind that that differences in productivity among workers are based on the fact that workers in an enterprise bring to bear not just the productivity of their own simple labor power but also all the other human factors they have appropriated over time. For example, a technical specialist directing a workshop contributes labor power as well as portions of other human factors they have accumulated: technological knowledge, administrative and management capacity, personal relations and values of community building and group interaction, etc. The market (depending on its degree of competition and perfection) assigns a value to all of this as a package, establishing a price for the overall labor of that person in the enterprise.

It is possible to combine both criteria, which may be the best approach. We know that, on the one hand, the market discriminates against certain types of work with lower qualifications while it privileges the performance of management tasks, and on the other, an enterprise that sets levels of compensation that differ too much from the normal market levels may lose workers whose contributions are undercompensated.

Whichever procedure is used the initial result will be absolute numbers, fixed quantities or sums of money. Because we are dealing with distribution of surplus, it is essential to convert these quantities into a weighted scale that can later be used to specify the percentages according to which each member receives their anticipated distribution. To create this weighted scale we will take as units of measurement the value of an hour or day of simple labor. Let us consider an example, in which remuneration is calculated based on a day of labor.11

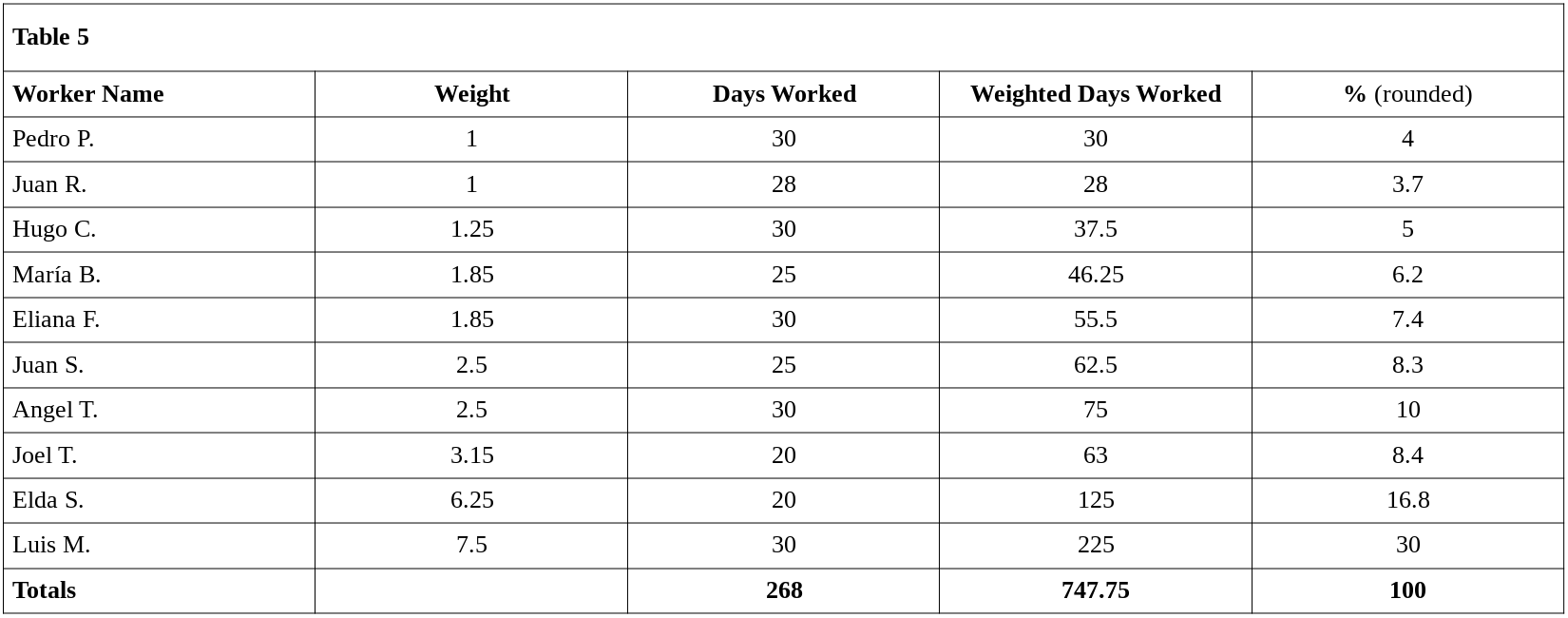

Applying the weighted value to the number of days worked by each member of the enterprise we obtain a figure for each worker (corresponding to the number of days of simple labor they have performed), on the basis of which we establish the percentages for distribution of anticipated earnings to each member. Thus, to take an arbitrary example:

This gives us the relative percentages we need in order to distribute anticipated earnings to the different workers. The amount each member receives depends on the total amount of surplus created and the percentage of the total surplus reinvested in the enterprise and thus allocated to members as labor shares of equity. We referred to this in the previous chapter when examining the criteria for distribution of surplus.

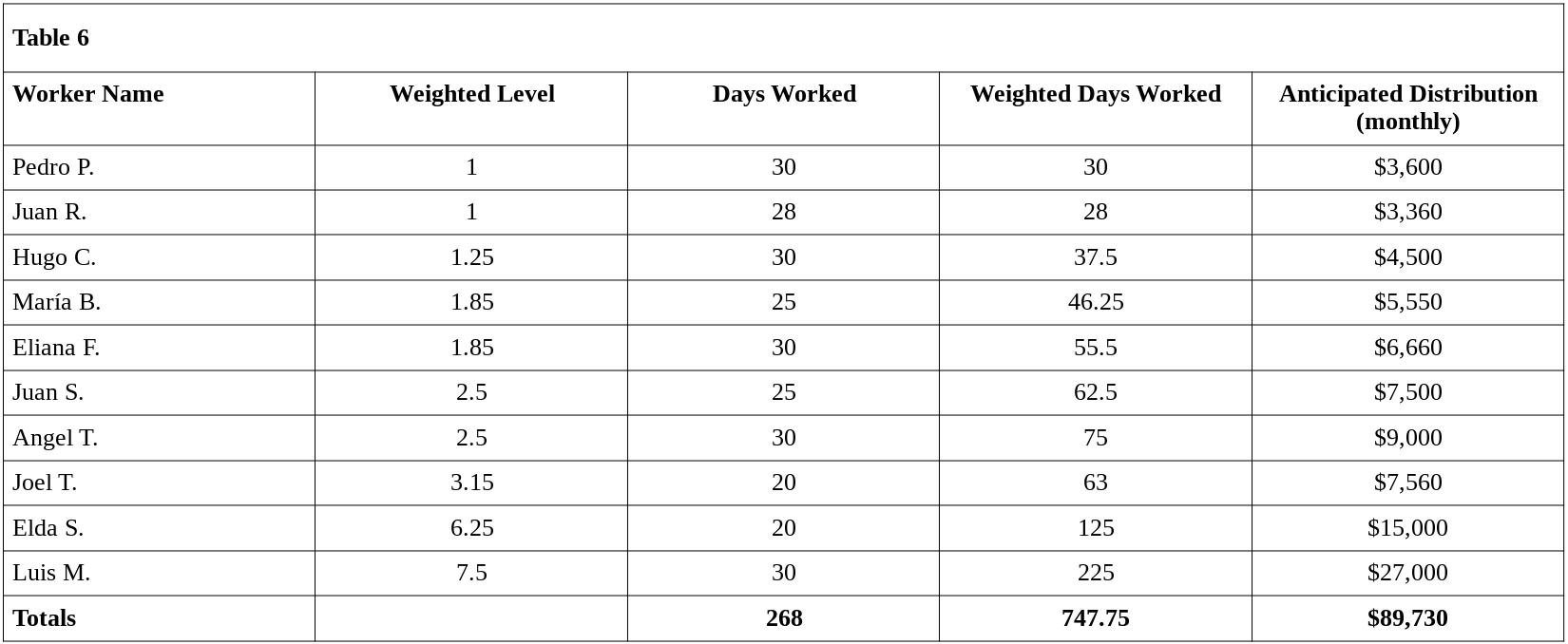

Now, workers need to receive on a monthly or more frequent basis some quantity of money for their labor. The payments they receive should not be considered wages or a salary, because they aren’t. As we noted, they are anticipated distributions of surplus. As these anticipated distributions are remuneration for contributions of labor and not of capital (the latter are remunerated at the end of the fiscal year, as decided by the members) it is just and fitting that the work performed by each worker be measured and weighted, according to the length of time they work and the type of work they do. Thus, if the anticipated distribution for a day of simple labor is $120 the monthly distributions for the enterprise in our previous example (Table 5) will be as follows:

All that remains is to make a clarification with respect to the question of labor relations in a workers enterprise. We realize that the differences in remuneration of labor in our example may seem puzzling or worrisome, given that we are talking about a cooperative enterprise. We have offered a clear explanation – the differences correspond to differences in worker productivity – that upholds the criterion of patronage distribution of surplus. What is revealed here is the fact that the labor contributed by members is not homogeneous. But how can we make sense of, and explain, this economic heterogeneity? Aren’t we dealing with contributions of the same factor for the same amount of time? Isn’t this attribution of different levels of productivity simply a way to justify or explain wage differentials that the market establishes for other motives?

To truly understand this issue we must remember that in this chapter what we term “labor” is in reality the productive utilization, during determinate periods of time (hours, days, etc.), of the combined human factors that each worker member contributes to the enterprise, not just their labor power.

A job requiring more technical training is, in effect, a labor activity carried out by a worker who has incorporated in their person a higher level of information and technological energy. (The technology factor is inseparable from the worker who possesses these elements, that is, the technology factor has not been objectified). In the same way, a job which involves greater administrative responsibility requires the labor activity of a worker who has incorporated in their person, and makes use of, a higher degree of the administration or management factor.

In this way, by paying some workers more for the labor they perform in the same amount of time as workers with fewer technical or administrative skills the cooperative is recognizing the different and superior contribution of economic factors made by “skilled” workers with greater technological or administrative capacity (factors that have undoubtedly signified some type of personal cost or sacrifice, studies, years of organizing experience, etc.).12

Having made this clarification, we can now move on to the analysis of the question of power and management in a worker enterprise.

Translated by Matt Noyes

Header image by Jeff Warren and Caroline Woolard. CC BY-SA 3.0

- 1A reference to the first principle of the International Cooperative Alliance: "Voluntary and Open Membership. Cooperatives are voluntary organisations, open to all persons able to use their services and willing to accept the responsibilities of membership, without gender, social, racial, political or religious discrimination.” - MN

- 2See Emmanuel Mounier, A Personalist Manifesto, Chapter 6 “A Personalist Comunitarian Civilization” https://archive.org/details/personalistmanif0000moun/page/88/mode/2up

- 3For example, a withdrawing member who owned 10% of the labor shares of the enterprise would be liable for 10% of the losses, measured in days of labor, incurred in the year of their withdrawal. - MN

- 4See Chapter 14 of this book. - MN

- 5So, while the nominal value of a share might be 100 hours of simple labor, the registered value is that same value expressed in monetary units, as calculated for the year in question. (Note that “nominal value” has a different meaning in capitalist enterprises, where it designates an accounting value that may be much lower than its initial sale price.) - MN

- 6The contradiction becomes more extreme in the case of cooperatives that operate foreign subsidiaries, giving rise to what one researcher has dubbed, “multinational coopitalism.” See Anjel Errasti Mondragon’s Chinese subsidiaries: Coopitalist multinationals in practice. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 36(3), 479–499. (2015). - MN

- 7This is typically countered by the use of member-only discounts and special offers. - MN

- 8Flexibility should also be the priority if the withdrawal of one or more workers becomes necessary as a result of a temporary reduction in business or production. In that case, it seems just and fitting that the affected worker member(s) leave their share of the “capital” and continue as a member of the cooperative (for a length of time specified in the bylaws) even while not working. Obviously, in such cases the member will continue to receive whatever remuneration is due to them as an owner of equity and continue to participate in governance according to criteria we will lay out in the next chapter.

- 9Often referred to as the “initial capital contribution.” - MN

- 10Distributed Cooperative Organizations, or DisCOs, do just this, tracking and remunerating not just livelihood work, that is, work which brings in revenue, but also “care work” – labor that maintains the C factor in various ways – and “love work,” pro bono labor that contributes to the commons or to social movements. See Principle 6 in The DisCO Elements. https://elements.disco.coop/DisCO-in-7-Principles-and-11-Values.html. – MN

- 11Based on an eight hour day at $15.00/hour. Note that this table does not specify the various types of factor contributions. - MN

- 12Note that the same analysis can be applied to C Factor elements, which also often signify personal cost or sacrifice, studies, etc. – MN

Citations

Luis Razeto Migliaro, Matt Noyes (2023). Cooperative Enterprise and Market Economy: Chapter 6. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/articles/cooperative-enterprise-and-market-economy-chapter-6

Add new comment