Inspired by Marcus Garvey, he innovated worker cooperative financing and legal strategies

When Clark Russell Arrington, III was a boy in high school he learned about Marcus Garvey, the great Black Internationalist, who in 1919 organized thousands of black people to invest $5 dollar shares to buy a commercial shipping line to transport raw material ad goods around the world to become the heart of an independent global black economy. The organization that Garvey founded, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, in just three months had successfully raised $500,000 to group purchase the Black Star Line.

But Garvey’s vision was clouded when the U.S. accused Garvey of securities fraud and jailed him for two years, crippling the strategic Pan Africanist organizing. Ironically the lessons that a young Clark learned about Garvey would inspire and informed his work years later as an adult who himself pioneered group fundraising, and legal solutions that would ensure democratic control of investments in worker cooperative financing.

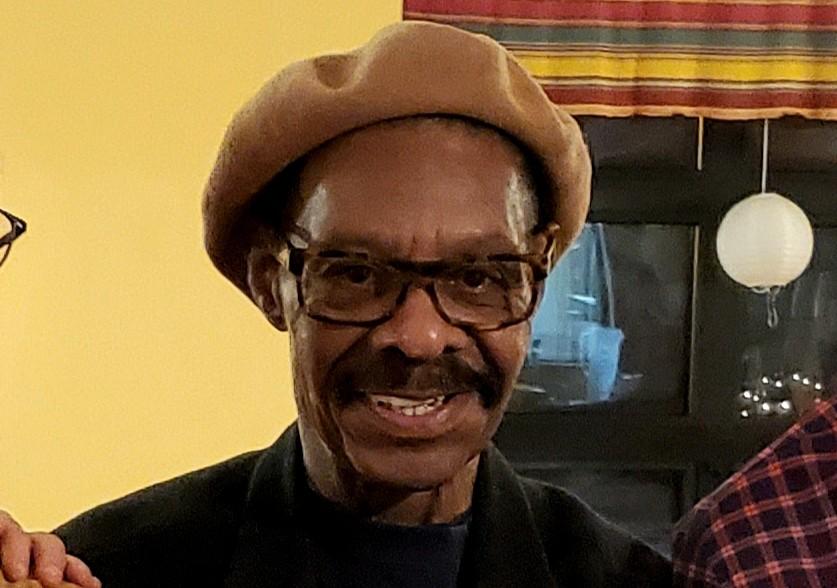

Arrington, who most recently served as General Counsel of Obran Cooperative LCA (a conglomerate of companies controlled by a worker-owned holding company), and who was the former General Counsel of Seed Commons (formerly The Working World), and Equal Exchange (where he pioneered a two-tier membership structure that ensured worker control for the cooperative which developed Fair Trade to assure farmers received fair prices in the coffee industry), died September 25, 2024 of complications from lung disease, according to his daughter, Lauren Arrington of Baltimore. He was two months shy of his 77th birthday.

In his 50-year career as a lawyer full of foundational work for worker cooperatives, agricultural cooperatives and democratic ownership, Arrington helped Southern black farmers’ agricultural cooperatives save their lands, developed a community economic development program in Tanzania and later became involved in the African Development Bank, supported a black construction workers in Los Angeles (APR Masonry Arts), generated capital for U.S. worker cooperative startups, and advised co-op loan funds.

“Over the past decades, if there was innovation in capital access for worker co-ops, he was right in the middle of it - Equal Exchange, ICA Group, CFNE, Seed Commons, and Obran,” said Micha Josephy, Executive Director of the Cooperative Fund of the North East. “He brought fearlessness, creativity, and wisdom to all of his endeavors.”

“A great tree has fallen in the forest,” said Woullard Lett, a professor and administrator at Southern New Hampshire University, the first academic institution in the U.S. to offer a program in Community Economic Development and where Arrington taught Law and Community Economic Development for 10 years. “Clark influenced a generation of community economic development practitioners,” in the U. S. and Africa where he helped to set up the CED program at Tanzania’s Open University.

Nicole Vitello, Vice President & Capital Coordinator of Equal Exchange remembers “Clark Arrington was an important part of Equal Exchange and he will always be remembered with great love and respect. Founders Rink Dickinson, Michael Rozyne and Jonathan Rosenthal credit Clark with believing in them and Equal Exchange more than they did during the early years. With his capital and legal expertise Clark validated and helped develop the radical ideas under which Equal Exchange still operates today- fair trade with farmers and a cooperative structure where worker owners hold the power and rent capital from investors on reasonable terms. Clark’s story is interwoven with ours and he will continue to influence us to think bigger and make more change for years to come!”

History in the Arrington Family Line

History flowed through his personal timeline. Clark Arrington III’s debut on the planet was paved with the rebellion of Africans kidnapped aboard a slave ship from West Africa for enslavement in the West. The Africans seized control of the slave ship Amistad on its way from sugar plantations in Cuba. The Africans landed the schooner in Long Island, New York. The Africans were seized by authorities and imprisoned in New Haven, Connecticut, where a well-known suit ensued over whether to return the captives to their homeland. By that time, the U.S. had abolished the International Slave Trade. The controversial case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, with John Quincy Adams arguing to free the Africans. In 1841 the United Missionary Society raised money to send the Africans back to their homeland. The Amistad rebellion was captured in a 1997 movie.

Money left over from the repatriation effort was used to form Talladega College in Alabama. It was at this black college where Clark Russell Arrington, II and Florence Gertrude Cooley met.

“I often speculate had there not been that uprising, had there not been that Amistad revolt, there would not have been a Talladega College, and in all likelihood, my mother and my father would not have met,” Clark told cooperative interviewer John Duda in a 2019 two-part Next Systems Podcast. “An African rebellion against slavery and against this extreme form of capitalism is what led to my existence.”

Florence Coley Arrington had earned her master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1946. Clark, III was born in Philadelphia on November 18, 1947. The family lived in a small tight-knit African-American community called La Mott in Cheltenham Township, PA.

La Mont, the community where young Clark grew up, was also rich in history. Originally the Civil War training site for black Union soldiers, it was called Camp William Penn. Lucretia Mott, the feminist and abolitionist, lived near the training camp. Her house was a stop on the Underground Railroad, a network of houses and people who supported the abolition of slavery and helped African Americans leave the South and come to the North where slavery laws were more relaxed.

Clark, III attended Palmer Memorial Institute in Sedalia, NC, a prestigious Black prep school for the black middle class. Clark attended school with children of celebrities, doctors and lawyers, professors and members of various diplomatic delegations. The school used the Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute cooperation model where the students were part of the school’s labor, working in the dining room, in building and ground maintenance and harvesting food.

At Palmer Memorial, Clark was taught from an Afrocentric viewpoint, and he learned about Marcus Garvey, Booker T. Washington, and W.E. B. Du Bois. “They were all powerful advocates of cooperatives,” Arrington recalled during the Next System Podcast.

Impressed by Garvey

Learning about Garvey, whose cooperative venture, the Black Star Line, intrigued Arrington. He recalled his thought processes:

“I looked at Garvey, and saw how he had accumulated a mass amount of capital from lots of people, small contributions, and created a serious enterprise, the Black Star Line, other businesses, and did it in somewhat of a cooperative manner,” Arrington said. “That impressed me. That led my thinking to, how a large number of people can pool small amounts of money to have large amounts of money in order to start businesses? From literally college on, that was always in the back of my mind while I partied and went to football games and chased and just had an outstanding social life, but I was always very concerned about capital accumulation and not replicating capitalism.”

At another point, Arrington also lays out how Garvey influenced his thinking:

“I wanted to learn about how to accumulate capital from a large number of people with small numbers of contributions,” Arrington said in a Next Systems Podcast in 2019 interview explaining how he got started. “I wanted to figure out, how could we do what Marcus Garvey did? Marcus Garvey was ultimately busted, jailed, excommunicated. I’m not sure the details of what the allegations were, but we know it was a black man amassing a tremendous amount of power and amassing the wealth of the black community.”

After high school Clark attended the University of Pennsylvania where he majored in sociology. Later she studied law at the Notre Dame University because he wanted to figure out those lessons he had learned from Garvey and those other early cooperators. He explained in that interview:

“I wanted to go to law school for social change. I wanted to learn about how to accumulate capital from a large number of people with small numbers of contributions. I wanted to figure out, how could we do what Marcus Garvey did.? Marcus Garvey was ultimately busted, jailed, excommunicated. I’m not sure the details of what the allegations were, but we know it was a black man amassing a tremendous amount of power and amassing the wealth of the black community. I wonder to this day, particularly after reading Collective Courage by Jessica Gordon-Nembhard: What if Garvey had been successful? What model would that have created in terms of African Americans basically accumulating capital for-profit enterprises and setting up enterprises?”

Arrington’s first job upon graduation from law school was with a Minority Enterprise Small Business Investment Company, Minority Venture Capital, which was a private company that invested in minority-owned or small companies. Arrington organized it while a law student. He then joined the US Securities and Exchange Commission as an attorney. At the SEC, Arrington was working with civil rights lawyers. He would call on that experience when he started working with the Federation of Southern Cooperatives where he learned about forming organizations to develop grassroots democratically-run companies.

Southern Black Farmers First Taught Him About Cooperatives

“We really gave him a baptism on the cooperative economy,” recalled John Zippert, who recruited Arrington in the 1960s to work with Federation of Southern Cooperatives. Together Arrington and Zippert spearheaded the creation of the Minority People’s Council to create worker-owned cooperative enterprises from donations from residents – similar to how Garvey raised money for the Black Star Line. This cooperative project that would result from the US Army Corp of Engineers $2 billion construction of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway through the Alabama Black Belt.

The Federation’s goal with the People’s Council was to ensure that the federal government plan to merge the two rivers would benefit and other low-income people by retaining land and ensuring that people in Alabama and Mississippi would get jobs and opportunities to form businesses (creating a structure to take in capital and make loans). “The Federation project was such a bold economic move by African Americans that “the Security and Exchange commission of Alabama came after us,” Zippert said.

Arrington recalled in the Duda interview that the Alabama securities police personally delivered a “Cease and Desist Order” on the Federation of Southern Cooperatives training center in Epes, AL. They were charged with allegedly violating Alabama securities laws for raising investment capital from AL and MS Black Belt residents. But the Federation and Arrington (with the lessons learned from Garvey, and his experience working as a securities and exchange attorney), with the assistance of a local attorney, successfully defended against the attack. Arrington explained in detail the defense in the interview:

“We fought these guys, and we won. We beat them. We forced them to back down, because we hadn’t sold a security. We were soliciting membership interests in a nonprofit that you could get your money back. There was no risk, and here’s the accounts. We haven’t spent any of this money. This money hasn’t gone for anything. It doesn’t pay my salary. It doesn’t pay gas for me. All the money that we’ve collected, and the Federation is covering everything else. At this time, it wasn’t so much. Yeah, we were collecting money, but the Federation was under attack, period, by the FBI, the IRS. The Minority People’s Council was set up as a 501(c)(4), not a 501(c)(3). We were allowed to engage politically.”

Innovation at Equal Exchange for Coffee Farmers

As Zippert noted, Arrington took the lessons from Epes to Boston, where one of the oldest and at that time largest worker cooperatives in the country, Equal Exchange, had a vision to create fair wages for coffee growers through Fair Trade. “Clark’s experience with us in Alabama and Mississippi prepared him for all the other challenges he faced and gave him a real understanding of what community economic development was about,” Zippert said.

Equal Exchange and the late jazz musician Miles Davis, invested in the same coffee cooperative, Kilimanjaro Native Coffee Union, Arrington wrote in an August 2024 What’s App CED National Program group. KNCU was the first African cooperative in the British African Commonwealth.

Worked with Ownership Associates Building Black Construction Cooperatives

After the Alabama work in the mid 1980's, Arrington moved to work as General Counsel of the Industrial Cooperative Association Group in Somerville, MA, where he applied his talents to assist in the creation of democratically-owned worker cooperatives across the country. At the ICA Group, Arrington met Christopher Mackin, who since the late 1980's has operated the Cambridge, MA, consulting firm Ownership Associates. Arrington began work with Mackin on launching construction cooperatives, first back in Alabama and later in Los Angeles. The Los Angeles project focused on black bricklayers who came together with the support of their union and the A. Philip Randolph Educational Fund to form APR Masonry Arts, a construction company named in honor of civil rights and labor leader A. Philip Randolph.

During its tenure, APR Masonry Arts built dozens of buildings, including the Boys and Girls Club of Watts and a building at the Los Angeles Zoo. The company employed up to 20 black masons previously discriminated against in that construction market.

Mackin, who in addition to working with Clark, became a close friend and at one time lived with him in a common apartment in Cambridge, commented that in addition to his brilliance and tenacity, a defining feature of Arrington’s personality and success was his laughter.

“That laugh of his was music. Like a symphony,” said Mackin. He commented that Arrington’s laugh "was a welcoming way of signaling to almost anyone he met that you were talking to a friendly human. He wanted to hear what people had to say, find common ground, join up and do good work.”

He Trained CED and Cooperative Practitioners and Young Lawyers

Similarly, Michael Swack, founder and former dean of the School of Community Economic Development at SNHU, and current professor at University of New Hampshire, and founder of its Center for Impact Finance, said of Arrington:

“When I think of Clark, I think of someone who was able to combine deep knowledge of the field of community economic development with a deep passion for improving the quality of life for people who didn’t start with any advantages in life. The ability to combine knowledge and passion with action was a defining characteristic of Clark’s life. He was also just a fun and engaging person to be around – kind, thoughtful and a good sense of humor.”

When Arrington returned to the U.S., he sat on several boards. CFNE’s Josephy observed that despite persistent health issues, Arrington insisted on staying on the CFNE’s board, and likely others. Arrington was on the CFNE’s board off and on since 1991.

Jamila Medley, former Executive Director of the Philadelphia Area Cooperative Alliance, recalls:

"Baba (father) Clark served on PACA's board at my request just as he returned to the US, and I was beginning my tenure as PACA's executive director. He was instrumental in helping me navigate my leadership, questioning visionary leadership vs. cooperative leadership.

“I was sitting in my kitchen yesterday with my husband, and we recalled the sophistication and brilliance Baba Clark brought to our home during a New Year's Eve party we hosted. I am grateful for the time I had with him and will miss him dearly."

Nijil Jamal Jones, the Chief Financial Officer and founder-worker-owner of Pecan Milk Cooperative, established in Atlanta in 2014, remembers, “When we were just Pecan Milk Cooperative, LLC. He asked 'Why does everybody keep making these LLCs?!'"

Clark also mentored many co-op lawyers and Black lawyers. Julian Hill, Associate Professor of Law at Georgia State University School of Law and director of their Community Development Law Clinics, states:

“Clark was one of two attorneys (the other being Carmen Huertas) who literally ushered me into this work and encouraged me when I was trying to leave the law firm in NYC. Clark immediately inducted me into his Legal Eagles. I learned a ton from him, and he was really the only brotha I knew who was an attorney doing this work. He was in many ways a model for me as a Pan Africanist committed to New Afrikan independence. Job well done. You will be missed. The Legal Eagles will have do what we can to just build on your legacy.”

Saadik Al-Ahmary is a SNHU CED alumni, organizer and coordinator of the 40 Acres and Mall Legal Team which represents the LA-based Downtown Crenshaw Rising, and which raised $30 million to buy the iconic 42-acre Crenshaw Plaza Mall in 2021 (the group is suing the seller for his refusal to sell to them). He said that Arrington taught him to be bold. “I will never forget the first day in his class as he taught us to push the limits of the law. And I’ve been doing that ever since,” Al-Ahmary said. “He’s had a lasting impact on my life and career, and his legacy will ever live on in me through my application of what he taught.”

Arrington was inducted into the Cooperative Hall of Fame in 2021, celebrating him as a co-op hero for his foundational work developing worker cooperatives, and innovations in co-op law. Jessica Gordon-Nembhard, 2016 Cooperative Hall of Fame inductee; author of Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice; member of the GEO Collective; and Professor at John Jay College, CUNY, remembers Arrington as “a giant in the worker co-op movement.

“Clark was a mastermind for co-op financing and innovative structuring; and he always thought big! There was no co-op challenge that he couldn’t find an answer to. In addition, Clark was a wonderful and caring human being – and Pan Africanist. He will be missed, but still lives in all of us whose lives he touched (which is many people); and in all the co-ops he touched.”

Arrington’s Most Impressive Accomplishment

With his long list of achievements with worker cooperative and other democratic employee organizations, what was Arrington himself most proud of?

Part of his work that did not end in Alabama was his return each year to the state to lead summer camp teaching young people about cooperation. In his own words, Arrington said:

“As the Economic Development Coordinator of the 21st Century Youth Leadership Movement’s summer camps in Selma AL, I taught 9-13 year old young people how to organize and operate a cooperative camp store,” Arrington told the podcast interviewer Duda. “After two days, they could prepare a balance sheet, an income statement, a budget and calculate their patronage dividend as of that particular time. To this day, I consider those summer camp experiences my most impressive accomplishments.”

Arrington’s eldest child Lauren participated in the 21st Century Youth Leadership camps as a youngster, and one of her first jobs after college was at the Federation of Southern Cooperatives. She recalled that one of the most special things about her father was how much he talked about his children with friends and colleagues.

“As his daughter, everywhere I went I was so known,” she said of her father. “He had already told them so much about me.”

Clark Arrington is survived by three wives: Karen McGill Lawson, who he met at Penn State, Margareta Summerville, who he met in Gainesville, AL, and Rahma Hassan, who he met in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; six children: Dr. Lauren Anita Arrington, Leila Arrington, Elisabeth Barden Msuku, Manal Arrington and Ayne-Alem Arrington and Che Russell Arrington; and six grandchildren.

Memorial celebration

An outdoor Memorial Celebration is planned for 2-5 pm May 24, 2025 at the One Art Community Center, in Philadelphia, PA which Arrington helped to organize.

In lieu of flowers

Donations can be made to college funds for two children Ayne-alem Arrington, a student at North Carolina A&T or Che Arrington who is finishing high school in Tanzania. If you would like to contribute to Ayne and Che's college education, you can find more info here: https://sites.google.com/view/clarkrarrington/home.

Author's note: I was Clark’s student in Law and Community Economic Development at SNHU’s Community Economic Development (CED) program from 2001-2003. A compelling teacher, Clark deeply impressed upon me (and the class) the idea of how to raise money for our community projects by seeking contributions from entertainers, athletes and even university endowments by requesting donation of .25 of 1% of their income – an amount that would barely be missed. This idea has long excited me because it always seemed so obtainable and we didn’t have to be at the mercy of established banks. I always keep this idea in my mind, and I expect it will soon bear fruit. Another thing I always appreciated about Clark was how “caring and sharing” he was. Once during a meal with another professor Chris Clamp, he offered me his home on one of the South Carolina sea islands, home of the Gullah Geechee people, descendants of enslaved Africans who kept alive their language, cultural and cooking traditions alive. He was heading to Tanzania and offered his house as a refuge if I ever needed it. I never forgot that generosity either! Clark was not just a great teacher and radical practitioner, but an awesome human being.

As the writer, it’s important to be open about my personal link with Clark, which in traditional journalism, might be viewed as possibly compromising objectivity. We were taught not to be a part of the story; hence I am telling my Clark story outside of his obituary. However, I believe knowing a person could allow you to write a better, deeper story because you know their beliefs and could better make connections to their actions.

Thanks to Clark’s daughter, Lauren Arrington, for providing me with his resume, and Cooperative Hall of Fame document and contacts for this story. He resulting obituary reflects the richness of the information about his life, though I chose only to tell the CED/Cooperative aspects of his life. There is so much more including his love and support of the arts. Thanks also to Jessica Gordon Nembhard for assistance with collecting quotes and putting me in touch with John Zippert. And lastly, appreciation goes to Red Emma’s cooperative member John Duda for his seminal interview that allowed us to take a peek inside Clark Arrington’s thoughts and to know details of his history. Thank you for creating that historical record of Clark’s work.

– Ajowa Nzinga Ifateyo, SNHU CED Class of 2003.

Addendum

What Really Happened To Garvey?

We always hear the story that the Jamaican-born man who declared “Africa for the Africans” was a bad businessman, and that and allegations of “fraud” is why he ended up in jail in the U.S., and ultimately deported. Some people know about how the FBI was at his meetings keeping an eye on him. But we, like Clark Arrington, don’t know the full story of what happened. At least one author provides more insight.

Charise Burden-Stelly, in her book, Black Scare / Red Scare: Theorizing Capitalist Racism in the United States, writes about how Garvey’s radical cooperative economic ideas and strategies for black liberation threatened Wall Street businesses expansion in search of cheap labor and raw materials. Garvey’s organizing threatened the very economic foundations of this country.

Radical black organizing as well as anti-imperialist organizing of communist movements threatened U.S. financial hegemony (just imagine the power of a United Africa where even today other countries expropriate cobalt, and other materials that the West rely on). The then-FBI director, the ruthless J. Edgar Hoover, first tried to have Garvey deported as a subversive alien, and when that failed seized on the charge of fraud to bring him and his organization, Universal Negro Improvement Association, down.

At the same time, Hoover, other agencies and other forces used rumors, lies and other tactics to discredit him and undermine his organizing black people, in particular, in the US colony of Liberia where enslaved Africans had been deported in an effort to thwart black uprisings in the U.S. against African enslavement. Note that the Amistad uprising which indirectly led to Clark Arrington’s parents meeting, led to an effort to fundraising to send the Africans back to Africa.

Dr. Burden-Stelly, after laying out many examples, concludes:

“…Garvey’s promotion of Black self-determination, challenge to Wall Street Imperialism in Liberia and excoriation of Euro-American expropriation of the African continent, made all-the-more dangerous by his ability to garner financial support for the Black Star Line from Black workers everywhere, propelled the U.S. government’s Black Scare and Red Scare construction of him as a radical agitator, an alien subversive, and an undercover Bolshevik, and aided in its rabid attack on him under the auspices of fraud.”

Burden-Stelly argues in the book that anti-radical repression is inseparable from anti-Black oppression, and vice-versa.

This book has vital lessons for how these policies play out today and that we must understand can apply to the continuing struggle to end subjugation and exploitation of people in the US and other places in the world where many people lack the basic necessities of food, shelter and clothing. Understanding these tactics and organizing to create a world where workers of all colors and nationalities can live in peace and thrive, as well as the planet, and all of us survives.

For more information on Garvey, contact: The Marcus Garvey Museum. (Thanks to the Archive Liberia for pointing the study group to this source. For me, it clarifies even more the nature of the attack on Garvey and the UNIA. )

–Ajowa Nzinga Ifateyo

Comments

Micha Josephy

October 28, 2024, 1:53 pm

Thank you for this article, Ajowa. The Opportunity Finance Network conference (2,500 people from community loan funds and stakeholders from across the country) recognized him as part of the in memoriam section of one of the plenaries. His legacy, influence, and inspiration lives on!

Add new comment