A Study of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

Abstract

The emergence in practice of worker cooperative ecosystems, which draws on the entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs) concept, has been largely ignored in academic research. Contrasting worker cooperative development efforts in Toronto with Montréal, we affirm there are multiple and multiscalar EEs in each region, including both a dominant capitalist and a worker cooperative EE. Productive enterprises like worker cooperatives, operating with a different logic than investor-owned firms, not only construct their own EE, but the relational connectedness of the worker cooperative EE to other EEs also plays a role in outcomes. Worker cooperatives have been less successful in navigating these dynamics in Toronto than in Montréal. Future research might seek to more fully specify the relational and multiscalar configuration of regions’ multiple EEs.

The entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) concept, which takes a networks-oriented, systems-components view of regional economies, has recently gained traction in economic development scholarship and practice (Harper-Andersen, 2019; Spigel, 2017; Stam, 2015; Wurth et al., 2021). Empirical studies of EEs typically presume regions are characterized by a single, geographically bounded EE (Alvedalen and Boschma, 2017), with generative activity primarily accounted for by productive enterprises, usually presumed to be investor-owned firms (IOFs). Meanwhile, local governments have recently created policies to enable more equitable productive enterprise models, including IOF alternatives like worker cooperatives (WCs; Spicer, 2020; Sutton, 2019). Community economic development practitioners have also begun to promote the development of “worker cooperative ecosystems” and “cooperative ecosystems”, as well (Hoover and Abell, 2016; Tanner, 2013). It is unsurprising that WCs are increasingly supported by some form of their own ecosystem. WCs are part of a broader class of productive enterprises, typically called hybrid or alternative enterprises by economic and organizational sociologists (Battilana and Dorado, 2010; Schneiberg, 2017), which operate according to a different logic than IOFs (Friedland and Alford, 1991; Rothschild, 1979), and which face different financing and governance constraints reflecting their “non-capitalist” or “more-than-capitalist” natures (Gibson-Graham and Dombroski, 2020). Accordingly, they likely require ecosystem components that complement and accommodate their logic. Despite the emergence of the WC EE concept in practice, there is little peer-reviewed literature examining its dimensions. There has also been little consideration of the broader implications of such specialized ecosystems.

We offer an analytic case study of the WC EE in Toronto, which we contrast to the more successful and well-documented shadow case of Montréal. Our study yields two broad findings. First, we confirm that WCs’ relative local success or failure reflects the strength and interconnectedness of their internal EE elements. We also affirm that these elements are multiscalar: actors in Toronto struggle to assemble the necessary components of a WC EE at multiple geographic scales, in contrast to Montréal. Second, we go beyond the existing concept of the WC EE, which to date has focused on its internal elements alone, to show how the relational connectedness of the WC EE to other EEs also plays a role in outcomes. Toronto's WC EE struggles to garner resources and support from the capitalist EE; it is also systematically disconnected and excluded from the region's nascent social enterprise EE as well. In contrast, Montréal's WC EE purposefully distances itself from the capitalist EE; it is also embedded within and reliably draws resources from a broader social economy EE in the region.

We discuss the implications of these findings for both the EE and IOF alternatives literatures, as well as for practice. By focusing on the IOF as the sole productive enterprise model and form of entrepreneurship, existing EE literatures have failed to consider the role that other EEs beyond the capitalist one may play in explaining the relational structure of regional economies. Existing academic literatures of IOF alternatives like the WC, meanwhile, also often focus on such entities in isolation, eliding over the role that their relational and multiscalar connectedness to other EEs may play in enabling their success. Future research might examine how, if at all, the comparative internal strength and relational connectedness of the various EEs affects broader regional economic outcomes. It might also examine, given the multiscalar nature of non/more-than-capitalist EEs, how or if the tenets of different comparative capitalism schools apply to alternatives and generate new insights in the process. For praxis, our findings affirm the conventional wisdom that local enabling policies and resources for WCs are relevant to their success. But they also suggest that such elements, while necessary, are insufficient alone to enable broader development of WC EEs. Relational connectedness to other EEs also matters.

From entrepreneurial to WC ecosystems

The EE depicts a set of social, political, economic, and cultural factors within a region that is coordinated to enable more productive entrepreneurial activities (Stam and Spigel, 2016; Wurth et al., 2021). The concept has gained significant traction in public policy around the world (Brown and Mawson, 2019). Although there is no universally agreed-upon model of the EE, Spigel (2017) suggests most proposed ecosystem elements can be categorized as cultural, social, and material attributes. These include entrepreneurial norms, historical examples of successful entrepreneurship, existence of investment capital and networks, and the physical presence of co-working spaces, supportive services and incubators, open markets, and supportive policy. In adopting the EE framework, policymakers and economic developers have designed and coordinated resources around entrepreneurs’ needs (Brown and Mawson, 2019). However, the EE concept has “considerable interpretive flexibility” (ibid) to allow policymakers and economic developers in diverse contexts to construe, according to their needs, the role and importance of different ecosystem elements. As a result, much of the EE literature analyzes how single institutions encourage entrepreneurship (Wolfe, 2005), or compare EE attributes in different regions (Harper-Anderson, 2019), including in Canada (Spigel, 2017; Spigel and Vinodrai, 2020). Despite the recent application of the EE concept to social entrepreneurial initiatives (Harms and Groen, 2017; Thompson et al., 2018; Wurth et al., 2021), such activities are often treated as involving something other than productive enterprise; these studies also still typically presume that specific city-regions are characterized by a single and IOF-centric EE. As critics have noted (Alvedalen and Boschma, 2017), most literature still presumes each region's EE is static, self-contained, and geographically bounded. Emergent work has acknowledged that these multiscalar and relational realities of EEs require further study and has also acknowledged critiques of existing EE scholarship and practice as a neoliberal project (Spigel, 2020; Spigel et al., 2020).

The emergence of WC ecosystems offers a case through which to empirically examine these assumptions and critiques of current EE scholarship, and to consider the implications of the potential existence of multiple EEs, as might be defined by different entrepreneurial needs existing within the same region (Harper-Anderson, 2019). Specifically, as alternative, but nonetheless productive, business structures, WCs operate under a fundamentally different logic than conventional, profit-driven businesses. Such IOF-alternative, productive enterprise forms are known to enable a qualitatively different type of entrepreneurship (see next section). As such, they may be unrecognizable to conventional EEs promoted by public policy and may also require different forms of support, materialized through their own coordinating networks.

WCs are collectively owned and democratically governed by worker-owners, to whom profits are distributed. WCs’ benefits are empirically well-documented. They include improved workplace conditions/satisfaction (Craig and Pencavel, 1992; Schwartz, 2012) and greater profitability and resilience/survival rates (Ben-Ner, 1988; Dickstein, 1991; Whyte and Whyte, 1988). Community benefits from WCs include poverty reduction (ibid; Dubb, 2016; Pitegoff, 2004); retention, ownership, and control of capital and wealth (Cummings, 1999; DeFilippis, 2004; Gunn and Gunn, 1991; Tonnesen, 2012; Wilkinson and Quarter, 1996), and improved economic opportunities for marginalized persons employed in exploitative industries (Matthew and Bransburg, 2017; Spicer, 2020). Nonetheless, WCs remain comparatively scarce in Anglo-American contexts (ibid).

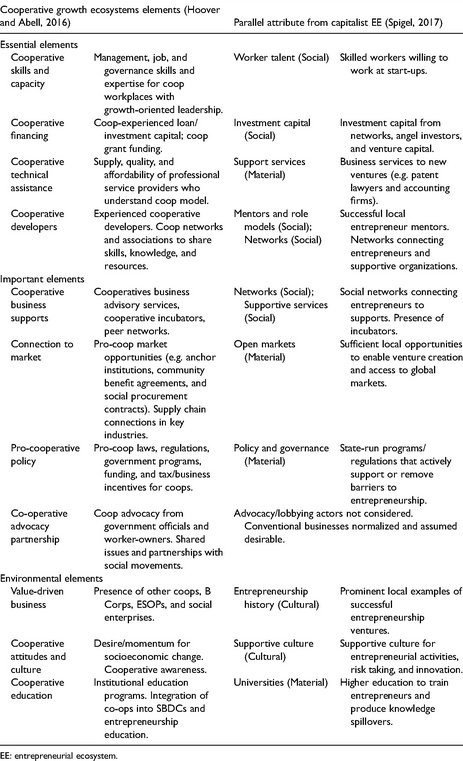

Recently, the EE framework has been used by practitioners to conceptualize the necessary factors to enable and encourage the development of alternatives, including both for WCs specifically, as well as more generally for a broader social and solidarity economy ecosystem (OECD, 2020). Building from Tanner (2013), cooperative developers Hoover and Abell (2016) provide the most comprehensive WC EE framework, synthesizing key factors into environmental, important, and essential elements. This model is effectively a WC version of Spigel's EE model (2017) with parallel ecosystem attributes that specifically function to support WCs rather than IOFs (Table 1). This framework claims WCs require a specific set of ecosystem elements, distinct and separately coordinated from those of IOFs (Akuno and Nangwaya, 2017; Hoover and Abell, 2016; Tanner, 2013). This is not surprising: cooperatives of all types have long been known to exist for a different purpose than traditional business, to serve member-owners’ needs. To that end, they have long deployed their own inter-firm coordination strategies to grow.1

Just as existing EE literature has centered the capitalist IOF and ignored these other forms of productive enterprises, this emergent grey literature on WC EEs similarly adopts an insular worldview, with little consideration of how different ecosystems relate. Furthermore, while this research on WC EEs does note the relevance of related alternative business forms, including other types of alternative/third-sector productive enterprise models, whether or not these other forms have their own separate and/or related EE has also not been well considered or examined. This is despite practitioners’ above-noted, emergent use of the concepts of both a WC EE and a social and solidarity economy EE, as well.

To our knowledge, there has been no peer-reviewed study testing how well or if the proposed WC EE elements (Table 1) explain the comparative quality or strength of WC development. Existing research has examined how alternatives, including cooperatives, struggle in liberal market economies (LMEs), which have been shown to prioritize the network coordination mechanisms of IOFs over alternatives (Mair and Rathert, 2019; Spicer, 2021), but this work has been cross-national in focus. Meanwhile, regional studies on cooperative enterprises not only elide over the question of how entrepreneurial networks and resources are relationally constructed but they also largely focus on “success cases” of high-activity cities and regions (DeFilippis, 2004; Spicer, 2020; Sutton, 2019) like Montréal (Bouchard, 2014; Levesque, 1990; Tanner, 2013). This makes it difficult to draw inferences about comparative success or failure, a well-known problem in success case-centric urban/regional research (Stein et al., 2017).

Toward a theory of multiple EEs

The development in practice of WC EEs offers an opportunity to advance existing EE and IOF alternative scholarship. What is treated as a singular EE by scholars is, in actuality, one of many: it is the capitalist EE, which seeks to coordinate and scale the activities of the profit-maximizing IOF. We thus recast the existing notion of the single EE as merely one of the multiple EEs that might be at work simultaneously in any given region. If one accepts the assumption that the profit-maximizing IOF dominates the activity of productive enterprises in many contexts today, particularly in liberal, high-income democratic countries like Canada, what has been treated as the single EE is likely merely the capitalist EE, which we might also expect to be dominant in the entrepreneurial landscape in such contexts. This begs the question: beyond the capitalist EE, how many others might exist? We suggest the answer to this question lies in literature on IOF alternatives, which yields the supposition that productive enterprises operating with sufficiently distinct and oppositional logics vis à vis the IOF might require their own ecosystems to advance their standing and position in capitalist-dominant contexts.

Although scholars in different academic fields use different naming conventions to conceptualize economic alterity, their work affirms that the IOF is not the only productive enterprise model. As noted earlier, a range of “hybrid” or “alternative” enterprise forms exist alongside the IOF, typically dominated by different types of logics than that of the instrumentally rational, profit-maximizing IOF (Battilana and Dorado, 2010; Friedland and Alford, 1991; Hansmann, 1996; Rothschild, 1979; Schneiberg, 2017). Their logics can also vary with respect both in the degree and qualitative nature of their alterity, variably involving “collectivist-democratic” instead of bureaucratic rationality in decision-making, and including pro-social goals alongside commercial ones within their hybrid “institutional logics” (ibid). Accordingly, such enterprises may be more likely to promote practices that are “non-capitalist” or “more-than-capitalist” in nature (Gibson-Graham and Dombroski, 2020).

Because these organizational models vary in their formal institutionalization and operating nature in different contexts (Chen and Chen, 2021), we suggest the number and relational configuration of these multiple EEs likely varies by place. It is possible that all or most alternative enterprises might be knitted together in a single and cohesive alternative EE. In France, for example, there is a robustly institutionalized social and solidarity economy, consisting of ∼20 organizational forms including the WC, many of which share access to common sources of financing, advocacy organization, and legislative tools (Spicer, 2021; Duverger, 2016; Seeberger, 2014), and reflecting significant overlaps in their logic and purpose. There, one finds evidence of a single “third-sector” EE that contains nested or embedded EEs operating as distinct sub-fields, each with their own organizational apparatus, including one focused solely on WCs (ibid). This is consistent with related sociological literature on the nested structure of organizational fields (Fligstein and McAdam, 2011). In other contexts, notably Anglo-American ones, where a more neoliberal version of third-sector enterprise prevails (e.g. “social enterprise”, as opposed to the “social and solidarity economy”), and where there are therefore fewer connections in the logic and operation of third-sector models with forms like the WC (Spicer et al., 2019), there may be multiple other third-sector EEs, which may be fairly disconnected from the WC EE.2

The various sociological and geographic literatures on enterprise logics thus provide a basis on which to understand why and how there might be multiple EEs in a given place. But what does this mean for specific IOF alternatives like the WC? In environments where the IOF-centric, capitalist EE dominates, it may mean that WCs not only must gather resources to construct the internal elements of their own ecosystem but they may also need to navigate other EEs for access to resources. Why might this be the case? Because the capitalist EE is constructed to enable IOFs, it may contain barriers or exclusions to the WC, thereby limiting the latter's range and reach over time. In fact, such exclusions have been well-documented to exist for the cooperative model in LMEs (Spicer, 2021; DePillis, 2021). Further, to extend emerging scholarship about the multiscalar realities of traditional EEs, other EEs are also likely to be multiscalar. This means that beyond gathering local resources to build the internal elements of their own EE, and beyond navigating the local, presumedly dominant capitalist EE for resources, as well, alternatives like the WC may need to navigate both capitalist and other EEs at higher geographical and jurisdictional scales that house legislation and advocacy frameworks. The necessity of these multiscalar actions may further compound the organizational burdens faced by WC EE actors in developing and sustaining themselves.

Although we cannot develop a comprehensive theory of multiple and multiscalar EEs in a single article, we can use the case of WC EEs to test these suppositions and to advance existing frameworks. Indeed, to move toward realizing properly specified analyses of Polanyian economic sociologies and geographies (Peck, 2005, 2013), which seek to move from a simple networks-and-embeddedness perspective to one which foregrounds the relational existence of plural networks (as operationalized, in this case, through different EEs), we need to examine actually existing cases of how these distinct systems of coordinating networks relate to one another. In the case of WCs, we might expect in LMEs like Canada, WC EEs operate in a comparatively more subordinate position in relation to the capitalist EE. But as consistent with economic geographers’ variegated capitalism critiques (Zhang and Peck, 2016) of simplistic national-level characterizations of economies (e.g. Hall and Soskice, 2001) we might also expect there to be significant variegation across different Canadian city regions in the degree and manner of WC ecosystems’ subordination to the capitalist EE, in ways which belie a coherent notion of a nationally scaled LME. Francophone Montréal, for example, has long maintained more robust social democratic mores which manifest in more supportive ecosystem policies for “institutional logics” of entrepreneurial alterity (Bouchard, 2014; Roy et al., 2021). Toronto, reflecting Ontario's Anglo-American nature, is perceived as less hospitable to such forms (Heneberry and LaForest, 2011). Given these differences, we accordingly might find significant sub-national variation in how WC EEs are relationally configured. But from existing EE literature, it is unclear how this might specifically manifest.

Research approach: Case selection and method

To test the validity of the existing WC EE framework, and to examine how, if at all, WC EEs relate to other EEs, we analyze efforts to develop WCs in Toronto, which we contrast with those in Montréal, which we treat as a shadow case (Soifer, 2021).3 With over 200 WCs employing over 10,000, Québec is home to about two-thirds of Canada's WCs (Hough et al., 2010) and is widely recognized for its “social economy” framework, which includes WCs and related organizational forms. They form an “integrated system” (Mendell, 2009: 181) of institutional leaders, policies, labour organizations, networks of cooperatives, and capital funds that have come together to coordinate a supportive “cooperative ecosystem” (Tanner, 2013: 54), with particular strength in Montréal. In contrast, Toronto, despite being the largest regional economy in Canada, is home to only around 20 WCs (Ministry of Government and Consumer Services [Service Ontario], 2020). Furthermore, Toronto's relatively underdeveloped WC presence contrasts with its robust capitalist EE that primarily supports IOFs. Therefore, a relational study of Toronto's WC EE can help answers questions about how multiple ecosystems coexist within the same region. By selecting two different regions within the same country, we eliminate cross-national policy variation as a confounding factor, while further exposing sub-national variegation as a key consideration.

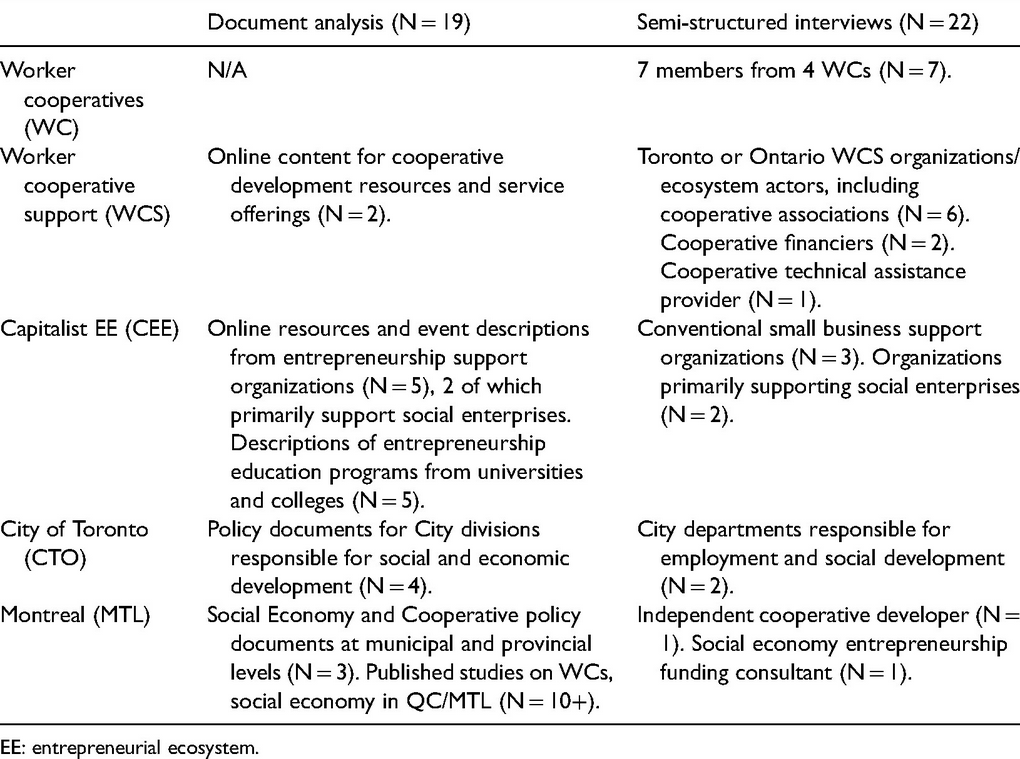

We generated data (Table 2) through semi-structured interviews (N = 22) and document analysis of relevant organizations (N = 19) in the Toronto and Montréal regions, with a primary focus on the cities themselves, and mapped thematically coded data onto the WC ecosystem framework following Hoover and Abell (2016) to facilitate cross-regional comparison. For our primary study of Toronto, we interviewed 20 individuals and analyzed documents from 16 organizations. In Toronto, we engaged in a purposive sampling of key strata of WC ecosystem actors (N = 13) to interview, including seven individual members from four Toronto WC, and six individuals from six Toronto or Ontario WC support organizations/ecosystem actors, including cooperative associations, cooperative financiers, and cooperative technical assistance providers, to map out the local WC EE and elucidate the challenges in assembling, connecting, and growing its elements. We also analyzed online resources from two WC associations to supplement interview data. We further tested the treatment of WCs by the capitalist EE, by analyzing publicly available documents from 14 organizations recognized as prominent actors in Toronto's Startup Eco-System Strategy (2017). Documents include online resources and event descriptions from five entrepreneurship support organizations, descriptions of entrepreneurship programs from five local universities and colleges, and policy documents from four municipal and provincial departments related to socioeconomic development. We further validated and supplemented document analysis through semi-structured interviews with five conventional business support organizations which do not focus on WCs (two primarily support social enterprises) and two City of Toronto government departments. Interview questions focused on the general availability of knowledge and services for WCs, how such models have been considered in organizational practices, and on how actors from across the broader business landscape are relationally connected to WCs.

Finally, we compare findings in Toronto to a baseline of a “successful” WC ecosystem in Montréal, which all 13 Toronto WC EE interviewees referenced at length, unprompted by interviewers, while describing challenges in Toronto. In addition to conducting secondary research on existing academic and grey literature (N = 10+ documents), which delineate most of the WC EE elements in Montréal, we further interviewed an independent WC developer, and a social economy entrepreneurship agent from the local small business support centre to validate and enrich our understanding of the ecosystem there (N = 2).

Using a “flexible coding” approach (Deterding and Waters, 2021), we thematically and systematically coded the interview transcripts and documents analyzed, specifically seeking to identify relationships, structures, and traits that might address the questions raised in the literature review and theory sections above on how, if at all, the various EEs relate and operate. For the internal elements of WC EEs, data collected from document analysis and interviews in both cities were also coded in accordance with practitioners’ proposed Worker Cooperative Ecosystem framework (Hoover and Abell, 2016, Table 1), which supported a systematic comparison to test differences and similarities between Toronto and Montréal.

Findings: Toronto's WC EE internally weak and relationally disconnected

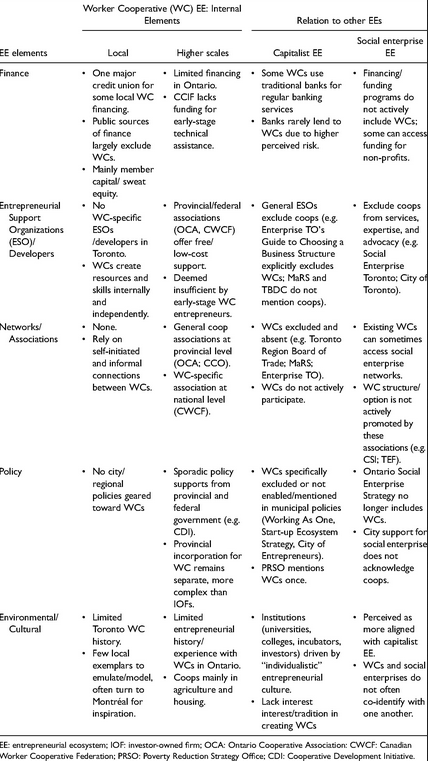

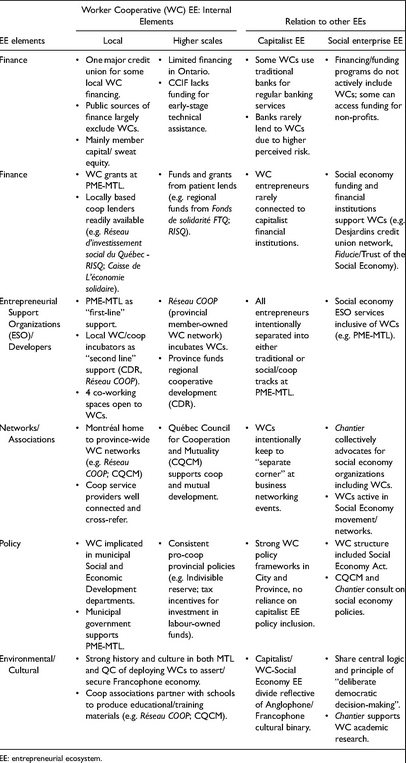

With respect to WC EEs’ internal elements, our findings confirm that Hoover and Abell's (ibid) proposed model well-captures their relevant dimensions. Toronto (see Table 3), which has a limited number of WCs, has a WC EE marked by poorly developed and weakly connected internal elements, in contrast to Montréal (see Table 4). These internal elements are also affirmed to be multiscalar: actors in Toronto struggle to assemble the necessary components of a WC EE from multiple geographic scales, while actors in Montréal enjoy a coherent set of internal elements locally and provincially. But we go beyond Hoover and Abell's existing concept of the WC EE to show how the relational connectedness of the WC EE to other local EEs also plays a role in outcomes: Toronto's WC EE is marked by unproductive relationships with both the capitalist EE and another third-sector EE. In Montréal, the WC EE benefits from a symbiotic relationship with a broader third-sector EE, to significant consequence.

Internal elements of Toronto's WC EE comparatively underdeveloped

Toronto's WC EE is internally fragmented, multiscalar, and without key elements that can reliably guarantee ecosystem stability. Toronto has few WC development financial and business support resources, networks, and policies; local WC EE actors must extend their reach for resources and support at higher geographic and jurisdictional scales, which are often limited in value. When higher scale elements are unstable and unreliable, dependence on these higher scale EE elements can be harmful to Toronto's WC EE. In contrast, Montréal has a rich set of elements that are well integrated into a coherent regional WC EE, making it resilient to higher level ecosystem changes.

Lack of internal elements locally leaves cooperatives dependent on limited-value resources at higher geographic scales

All WC interviewees experienced challenges in finding affordable and suitable cooperative development resources and technical assistance within Toronto, including legal, financial, and business support, as well as formal local cooperative networks, which often drive WC entrepreneurs to look for resources outside the city, province, and even country. This need to reach outward is in part because there are no formal cooperative networks in the Toronto region, and cooperative development resources are mostly provided by federal and provincial associations, which are physically located outside of the City. Provincially, the Ontario Cooperative Association (OCA), the main cooperative development support organization in Ontario, was displaced from Toronto to Guelph, a small city near Toronto, to save costs and to better service agricultural cooperatives concentrated in Guelph, according to an interviewee. The OCA also works with the Canadian Worker Cooperative Federation (CWCF) and its CoopZone branch to deliver cooperative development services. However, one WC interviewee, who also serves on the Board of Directors of the CWCF, remarked that there is a heavy reliance on the expertise of a few experienced and effective veteran cooperative developers scattered around the country, most of whom are located far from Toronto, reflecting a severe shortage of cooperative development expertise. Relatedly, another interviewed WC stated there were too few resources for WCs in Ontario and Canada, and intentionally sought out relevant WC resources from other nations.

Additionally, free preliminary cooperative development resources made available by the province to Toronto WCs were deemed inadequate or unfit by WC interviewees, and in-depth organizational consulting/development services from higher-scale cooperative support organizations were found to be unaffordable. For the most part, cooperative entrepreneurs often obtain initial free resources and consultations from the OCA. However, an interviewee from a credit union in Toronto observed that the cooperative entrepreneurs they refer to the OCA “somehow keep coming back to [the credit union] for information on co-op development even though it's not [their] area of expertise […] there seems to be a need for hand-holding” in the cooperative development process, which the interviewee perceived to be missing in OCA's offerings. Early-stage cooperative support is further complicated by “convoluted” government processes associated with cooperatives, as cooperative incorporation in Ontario has always been separately administered from conventional business structures and involves a more “complex and inaccessible” procedure relative to other structures, according to a WC EE interviewee. Relatedly, all interviewed WCs remarked that available free or low-cost cooperative support services in Ontario and Canada were not entirely helpful to their organization, and free consultations “eventually all turned into sales pitches that [the cooperative] could not afford”. WC entrepreneurs also have trouble finding financial support for such business services. Although there is $25 million available in Canadian Cooperative Investment Fund, it does not fund the technical assistance that early-stage and small cooperative entrepreneurs need, according to interviewees.

Due to the lack of accessible, affordable, and suitable cooperative support, all interviewed WCs reported conducting cooperative organizational development work internally, often creating from scratch their own governance structures and business plans, managing financial accounts, and establishing human resource development procedures. In the WC EE framework (Hoover and Abell, 2016), such functions are often performed by cooperative development organizations, but Toronto lacks effective organizations for this element function. As a result, member-owners at individual WCs have been forced to develop these sectoral organizational development skills, which reduce their time and capacity available for core business functions. In particular, two interviewed WCs were repeatedly referenced by other interviewees as important sectoral development resources in Toronto (in addition to the OCA and a local credit union), for other cooperative entrepreneurs in Toronto. WC entrepreneurs themselves stated they network informally via these two key WCs, through ad-hoc knowledge-sharing and referrals to technical assistance providers that “understand how cooperatives work.”

There is a similar reliance on higher jurisdictions for pro-cooperative policies, which makes Toronto's WC EE vulnerable to higher level cooperative policy changes. Among Toronto's municipal socioeconomic policy documents that we analyzed, including the Working as One workforce development strategy (2012), the Start-Up Ecosystem Strategy (2017), the City of Entrepreneurs (2021) strategy, and the Poverty Reduction Strategy (2017), only the Poverty Reduction Strategy mentions WCs, and only once in passing. This sole appearance is directly related to the Poverty Reduction Strategy Office's (PRSO) explicitly equity-seeking and partnership-based approach to coordinating anti-poverty initiatives, which an interviewee noted allows the PRSO to be particularly exploratory and imaginative in their approach. Interviewees at city agencies were uncertain, however, as to whether the WC model could gain further traction in City departments associated with economic development and employment services.

Due to the lack of local government support, policies that impact Toronto's WCs thus largely reside in provincial and federal levels of government, which have not consistently supported WCs. As a result, Toronto's WC EE can be vulnerable to policy changes at higher scales. An interviewee noted that in 2009, national and provincial cooperative associations lobbied for pro-cooperative legislative modifications to the Co-operative Corporations Act to effectively eliminate many incorporation barriers, with only limited success. Meanwhile, the federal Cooperative Development Initiative (CDI) provided national funding for cooperative advisory services between 2009 and 2013. The CDI was particularly valuable to cooperative entrepreneurs in places with little existing cooperative development experience, such as Toronto, to hire external cooperative developers and technical support (Corcoran, 2019). When the CDI was terminated in 2013, interviewees stated it was a significant loss for Toronto's WC sector. Although the funding gap was temporarily filled by Ontario's provincial Social Enterprise Strategy – which, according to interviewees, cooperative developers leveraged to assist WCs currently actively in Toronto – this strategy was cancelled in 2018, inhibiting the subsequent formation of new WCs (Service Ontario, 2020). Overall, Toronto's WC EE lacks reliable policy support at all three jurisdictional scales. Moreover, the lack of consistent and localized cooperative policies to support WC entrepreneurship in Toronto amplifies the impact of changes in relevant federal and provincial policy and resources, on which Toronto's WC EE is dependent.

Montréal's internal WC EE elements are coherently integrated and self-sufficient

While the national CDI's launch and termination (referenced above) had significantly impacted Toronto, an interviewee there suggests that it had virtually no impact in Montréal. This resilience is partly attributable to the comprehensiveness and interconnectedness of Montréal's internal WC EE elements locally. Cooperative development resources and technical assistance are well developed and networked, and buttressed by reliably supportive provincial cooperative policies. Notably, many WC resources/supports are shared among the “social economy” (see next sub-section).

In Montréal, business support, technical assistance, and financial resources for WC entrepreneurship are readily available, easily accessible, and well-networked regionally. A key point of entry for entrepreneurs to access business support in Montréal is PME-MTL, a small business support and funding centre contracted by the City of Montréal with funding from Québec (PME is the French equivalent of the English SME, small and medium enterprises). Entrepreneurs are separated into two streams of services upon entry: conventional businesses; and social economy organizations, which include cooperative enterprises. For the social economy sector, PME-MTL has dedicated staff and grants to fund around 45 social economy initiatives each year, with 20% of them being cooperatives, according to an interviewee there. PME-MTL is also well networked with other cooperative support actors. Another interviewee conceptualized the PME-MTL as the première ligne (first line) of support for WC entrepreneurs, offering general business development and governance advice, as well as introducing the WC option to suitable entrepreneurs. For entrepreneurs who require more extensive assistance, PME-MTL staff would refer them to either the Co-opérative de Développement Régional (provincially established regional cooperative development body) or Réseau COOP (a cooperative network owned by member cooperatives), which compose the deuxième ligne (second line) of support for WC entrepreneurs, according to interviewees there. In particular, Réseau COOP provides a high-quality incubator program for cooperative entrepreneurs; 70% of cooperatives exiting the incubation process are deemed well capitalized by these organizations. There are also four co-working/incubator spaces for collective enterprises, including WCs, to support networking and stoke development.

Montréal's WC EE is also multiscalar. Unlike in Toronto, however, there is reliable support from both municipal and provincial levels as the cooperative structure is well institutionalized in Québec's provincial financial and legal frameworks. Financially, WCs and their support organizations are bolstered by two major province-wide cooperative funds: the Caisse d'économie solidaire, a Desjardins credit union fund, founded by labour union CSN for social economy investment, and the Fonds Locaux of the Fonds de solidarité FTQ (the Fonds), a renowned labour-sponsored investment fund that is solely capitalized by investment and retirement savings of the FTQ union workers (Tanner, 2013). The Province also offers a favourable 15% tax credit to investments in labour-sponsored funds (Tanner, 2013). These funds, among other impact investment opportunities, actively promote and reduce barriers for cooperative entrepreneurship. To date, the Fonds has financed, through the Fonds locaux program, $149 million on 4,922 projects, creating over 42,000 jobs in the province, including jobs at WCs (nb: not all these jobs or projects involve WCs, FondsFTQ, 2018). Given the sheer size and prominence of these social economy financial institutions, interviewees stated the federal level CDI funding had little impact on Montréal's WC EE. Moreover, Québec (in contrast to Ontario) has an indivisible reserves policy framework for cooperatives, which directs profits generated from the sale of a cooperative back into the sector (Tanner, 2013). This provision ensures that cooperatives act as a “public and multi-generational good and not just something that is going to benefit the founder” (Corcoran, quoted in Tanner, 2013: 56) and “fundamentally socializes co-operative capital [and assets]”, according to an interviewee.

Finally, the cooperative structure also holds a significant and well-documented position in Québec's social, political, and economic history, affecting entrepreneurial norms locally in ways that favour local take-up and institutionalization of the model (Diamantopoulos, 2011; Levesque, 1990; Quarter, 1990; Tanner, 2013). Today, large cooperative federations are intimately involved in state-led provincial economic development, which enables both the expansion of existing and new cooperatives and associations, and the institutionalization of new pro-WC economic development strategies, which legitimizes WCs as a “viable replacement strategy for the capitalist structure at the fundamental level of property and assets”, according to a Montréal interviewee. Overall, Montréal's WC EE is characterized by an expansive set of readily accessible and well-integrated business services, technical assistance, and financial opportunities.

Relation between Toronto's WC EE and other EEs are unproductive

Interviewees in both Toronto and Montréal perceive the WC and capitalist EE to be incompatible with each other. In Toronto, however, the lack of resources within the local WC EE has steered WC actors to seek resources and support from the capitalist EE. Such efforts to connect with the capitalist EE have been met with systematic resistance and exclusion, not only from the capitalist EE but also the region's nascent social enterprise EE. Interviewed Toronto actors and analyzed documents confirmed a lack of recognition and exclusion of the cooperative legal structure among traditional/capitalist and social enterprise service providers.

Excluding cooperatives in Toronto's capitalist EE

The WC as a legal structure and business model is obscured, segregated, illegible, and unrecognized in various parts of Toronto's capitalist EE. Almost all interviewees in Toronto, including those in the capitalist EE who knew about WCs, mentioned “lack of awareness about cooperatives” among the general public as a key barrier to growing cooperatives, noting in particular the lack of cooperative-related content in public education curricula (three interviewees) and start-up information sessions (two other interviewees) such that “entrepreneurs and people entering the workforce do not know that the cooperative structure is even an option that exists.” These observations were affirmed through document analysis of the descriptions of entrepreneurship programs at Toronto's universities and colleges, and event descriptions of small business entrepreneurship information sessions offered by Enterprise Toronto throughout 2019–2020, none of which mention cooperatives.

The cooperative legal structure is also segregated and unrecognized in general government business services, which results in their exclusion from agencies’ programs. For example, a WC interviewee noted that the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB), which is the “go-to organization in terms of worker safety” did not “have knowledge of cooperative structures”. The WSIB had denied the WC member-owner's health claim because worker-owners, or “part-owners”, were not eligible for health claims. Similar exclusions occur in business services as well. According to three Toronto WC EE interviewees, because WCs have operational needs and economic logics that are different from traditional businesses, mainstream business service and technical assistance providers-such as lawyers, accountants, and insurance providers-tend to lack cooperative knowledge and expertise to effectively include WCs’ needs into service provision. As a result, WCs’ interactions with mainstream agencies and service providers were generally unsatisfactory. One WC relayed that a general business support services provider offered “pointless” assistance and “gave bad advice” because they lacked training on cooperatives. Another recalled a service provider who had claimed, falsely, they “[knew] how non-profits and cooperatives [worked],” which caused more confusion and was ultimately counterproductive. Concurrently, cooperative service provider interviewees, in recounting their past experiences working in capitalist service firms, reflect that “not many people know about co-ops,” and that “there's not enough business for [service providers] to get familiar with [cooperatives]” and develop the relevant expertise.

The exclusion of WCs from mainstream government and business services was noted as an obstruction to the kick-starting of entrepreneurial activities in Toronto's WC EE. Business lawyers with non-profit/cooperatives expertise suggested that entrepreneurs usually do not start a business based on the desired business structure; rather, their business purpose, plan, and leadership qualities usually lend themselves to one structure over another. Therefore, the best way to enable cooperatives is to “put an emphasis on, give space for, or promote businesses that look like cooperatives” and to put the cooperative option “on the table” along with other alternatives when entrepreneur(s)’ values align with that of cooperatives (Interviewees; Alvarez, 2017). However, when the cooperative structure is not recognized as an option by government institutions and business service providers, entrepreneurs cannot even consider them. Thus, the mere lack of exposure and familiarity to the structure, as established in the literature, makes the model inaccessible and unattractive for most entrepreneurs and investors (Schwartz, 2012).

Some organizations explicitly state that they exclude the cooperative option in knowledge dissemination and service provision, due to organizational skepticism of the model. In its “Guide to Choosing a Business Structure”, Enterprise Toronto (2020), the Small Business Service Office for the City, explicitly states that it “does not deal with cooperatives”. An interviewee there reasoned that clients would not be interested in cooperatives even if cooperatives were included in business services: “I think the majority of people are really looking to start traditional businesses. I don't think there's a lot of people who are looking for cooperatives, because it takes a lot more coordination, bigger networks.” This skepticism toward cooperatives assumes that most entrepreneurs already know about cooperatives and have decided for themselves that they are uninterested in collective businesses, which based on WC interview data, may not be the case. A WC EE interviewee characterizes this condition as a “catch-22” situation: if entrepreneurs never know about the WC model, how could they ask for advice and support for them? Overall, the Toronto WC EE is, on institutional, cultural, and technical fronts, systematically disconnected from the capitalist EE, which has significant resources for traditional businesses alone.

In Montréal, after the PME-MTL's initial stage of sorting businesses into traditional and social economy structures (discussed in the preceding section), the WC and capitalist EEs are also separate. But interviewees stated this was intentional: they are “oil and water” whose fundamental logics are divergent and should be kept separate. Given the robust set of internal elements that already exist in Montréal's WC ecosystem, interviewees instead note the strategic importance to build networks, connections, and collaboration opportunities between ecosystem elements to improve ecosystem capacity, self-sufficiency, and competitiveness of WCs in an environment where capitalist enterprises are dominant. This divide well maps onto the “Francophone vs. Anglophone” dichotomy that characterizes many facets of Québec society (see Diamantopoulos, 2011; Levesque, 1990; Quarter, 1990). According to one interviewee, the idea that collective rights can override individual rights has been “consolidated over 120 years to build an economic culture in Québec distinct from the individualistic Anglophone capitalist logic.” Montréal's WC EE is one manifestation of such long-standing cultural separation, which has distilled “two realities in Québec” where Anglophone and Francophone businesses are often embedded in different ecosystems: for example, “if you are Anglophone, you don't bank with Desjardins,” the largest credit union network in Québec. This Francophone socioeconomic logic has thus been imprinted onto the “social economy framework” within which the WC model is included (next sub-section).

Thus, WC EE actors in Montréal are intentionally kept separate from the capitalist EE. To illustrate, in Montréal, there are separate “corners” at business networking events and conferences for social economy actors, including WCs, to interact and build relationships. Even when capitalist and social economy actors are co-located, as in the PME-MTL, entrepreneurs are required to choose either the private or social economy service stream from the start; social economy agents at the PME-MTL then typically connect cooperative entrepreneurs to external cooperative service and resources providers who “understand the cooperative mentality”, and do not typically connect them to providers associated with PME-MTL's private stream. Although staff between the two streams are theoretically able to draw on each other's expertise and knowledge to facilitate inter-EE connections, a PME-MTL agent noted only two such instances over the past six years. Inter-EE segregation is perceived to be especially pertinent to protect WCs from being co-opted by “pollution from the private sector”, as they tend to operate in sectors that are traditionally occupied by capitalist firms with similar profit objectives, with the key difference being that cooperative capital is non-divisible and therefore socialized. This approach is markedly different from that of Toronto's WC EE, which attempts, with little success, to garner resources from the capitalist EE.

Toronto's WC EE separate from social enterprise

Toronto and Montréal's WC EEs also differ in their overlap and connections with broader third-sector enterprise ecosystems (Tables 3 and 4). In Toronto, the WC EE faces exclusion from the local social enterprise sector/EE. In comparison, as our findings have continuously alluded, Montréal's WC EE enjoys shared and symbiotic resources and networks with the broader social economy EE, within which the WC EE is nested.

Two WC advocates in Toronto reported active efforts to garner support and interest from the local social enterprise sector, which has a more prominent policy and economic presence, but lamented that the sector “doesn't have time for co-ops”. These attempts were met with similar forms of exclusion as from the capitalist EE, reflecting a misalignment in logic between WCs and Toronto's social enterprise EE. Today, the cooperative structure is not documented or included in any of the examined social enterprise frameworks produced by government or social enterprise associations in the region. Rather, Toronto's social enterprise framework prioritizes charitable non-profit organizations that have an income strategy, or for-profit businesses and organizations that claim to deliver social or environmental benefits through products or services (City of Toronto, 2020; Ahmed, 2016). Although Ontario's Social Enterprise Strategy initially explicitly recognized cooperatives as the origin of social enterprises, newer iterations of the document no longer mention cooperatives (Government of Ontario, 2021). The term “social enterprise” was originally used to promote cooperatives/mutuals to combat economic exclusion (Teasdale, 2011), but two interviewed cooperative advocates contend that Toronto's conception of “social enterprise” is a loose label rather than formally legally structured, consistent with existing research on how social enterprises in Anglophone contexts are often poorly defined and can be neoliberal in nature, achieving social change through investor-led markets (Dey and Steyaert, 2010; Spicer et al., 2019), in contrast to the Francophone concept of a social economy. A WC interviewee evaluated “how [the provincial government has] handled the framing of social entrepreneurship” as “trying to be as friendly to capitalists as they can” and that “the Canadian government has an active disinterest in promoting things like cooperatives [because they are] actually a form of democratization of workplaces”. In this sense, far from being a natural alliance to the WC EE, Toronto's social enterprise sector is incompatible with, and arguably oppositional to, the “anti-/more-than-capitalist” logic inherent to the WC structure.

To that end, Toronto's social enterprise sector demonstrates skepticism toward the cooperative model, as its leaders have shown dismissal and disinterest in including cooperatives in the social entrepreneurship framework, according to interviewees. Operationally, interviewees from two social enterprise support organizations noted although their organizations are aware of cooperative associations, they do not actively promote or consider cooperatives in their services.

Rather than being a stand-alone ecosystem, Montréal's WC EE is, as documented in literature (Mendell, 2009; Tanner, 2013) and affirmed by interviewees, naturally integrated and nested within the local “social economy”, which Mendell (2009) refers to as an “economic development social movement” institutionalized through multi-stakeholder alliance between social, labour, cooperative, and community movements. This “movement approach” to cooperative development allows the WC EE to maintain its individual integrity while remaining “porous” and allied with other collective enterprises that share similar socioeconomic values to share ideas and resources beyond the internal ecosystem, according to an interviewee. WCs are also integral contributors to the social economy movement, which, championed by the Chantier de l’économie sociale (Chantier), unifies the voices of government, community actors, and diverse social movements advocating for women, labour, and cooperatives to push for alternative economic development strategies with “deliberate democratic decision-making” as the guiding principle (Mendell, 2009; Mendell and Neamtam, 2010). Through its extensive, collaborative, and dynamic networks and distributive governance, the Chantier has institutionalized efforts to produce education programs, create resources and funding, and recommend public policy innovations to develop the social economy sector, which includes cooperatives, associations, mutuals, collective enterprises, and other organizations that centre economic democracy (Tanner, 2013). Ultimately, Québec's social economy is a solidarity-based movement that centres processual and economic democracy and collective activism – as opposed to Anglophone social enterprises centred on “doing well by doing good”. This yields a robust and rich social, cultural, and economic context for the social economy enterprises, including WCs, to thrive. In practice, the embeddedness of the WC EE within the broader social economy EE has enabled WC entrepreneurs to reliably mobilize the resources available in the social economy, and to contribute back to it as well, thus promoting mutual ecosystem reinforcement. In fact, an interviewee argued that, through inter-sectoral networks and alliances, some sectors in Montréal's social economy EE are achieving a critical mass that can “autonomously facilitate scaling for existing and emergent social economy entrepreneurship.”

Further, because the “social economy” is inclusive of both more-than-capitalist legal structures and more loosely defined social purposes, there are ongoing debates, discussions, and formal negotiations in the Montréal social economy community about “what should count as part of the social economy,” according to an interviewee. At PME-MTL, for example, there is a “selection committee” composed of seven diverse social economy actors, including organization directors, financial service providers, and academics, to make final funding approvals for social economy entrepreneurs and ensure collective decision-making about what should be included in the social economy. WCs, however, are “automatically included” due to their indivisible reserve provision, democratic legal structure, and historical legitimacy. Collectively, this evidence suggests that in the Montréal context, the WC EE is located within a broader social economy EE.

Discussion and conclusions

Through the study of Toronto's WC EE and comparison with Montréal's, we have affirmed the co-existence of multiple EEs, each underpinned by different organizational logics, and which are relationally institutionalized in different ways. The case data clearly indicate Toronto's WC EE has internal elements which are weakly constituted, and its relationship to other EEs is neither productive nor beneficial, in contrast to Montréal. The success of WCs would thus appear to depend not only on the presence and vitality of its internal WC EE elements – which is consistent with the existing grey literature on WC EEs – but also on how well those elements are networked to multiple, other EEs, and at multiple scales, as well. Beyond these case-specific findings, what does this imply for broader theory and practice?

First, though they are not profit-maximizing enterprises, WCs’ EEs appear to operate at multiple, overlapping scales, consistent with theories of variegated capitalism (Peck and Theodore, 2007) which to date have largely been applied to traditional, profit-maximizing enterprises (i.e. IOFs). Much like capitalist enterprises, the organization of regional WC EEs thus seems at least partially dependent on variegated structures and forces operating at higher geographic and political scales. Further, and as also consistent with a variegated capitalism approach, a singular change at a higher geographic scale can result in different outcomes at lower scales. As discussed, the cancellation of the national CDI significantly distressed Toronto's WC ecosystem but had minimal impact on Montréal. This variegated, multiscalar nature of the WC EE empirically affirms existing critiques that have highlighted the undertheorization of multiscalarity in EE scholarship (Alvedalen and Boschma, 2017).

Second, while the WC EE concept appears to have been useful for cooperative development practitioners, to date its usage has been marked by the same mis-specification as the broader EE framework. Specifically, by centering the internal elements of the WC EE, it has not considered how its relation to other EEs might play a role in explaining WCs’ successful development. Regions with incomplete WC EEs – like Toronto – may additionally suffer from a lack of resources from both the broader capitalist EE, as well as from other third-sector EEs. Further, relations between the WC EE and these other EEs might be constituted quite differently in different regions, as noted in the preceding section on Montréal, in ways which variably support or undermine the WC EE's development.

Overall, our findings confirm practitioners’ model of a distinct WC EE, which in turn affirms that regions do not simply contain a singular and single-scaled EE. Future research might go beyond describing the multiple, multiscalar ecosystems which exist in different regions, as we have done here, by further interrogating their relational dimensions: how do these multiple ecosystems systematically interact, connect, or nest within each other, across contexts? How are they constituted relationally, and to what consequence for regional economic development? More academic attention to the networks and nesting of multiple ecosystems might help us move toward a dynamic, relational theory of EEs.

Such research might seek to deploy two different frameworks to further develop the EE concept. As already noted, variegated capitalism could be usefully applied to EEs, to understand how both capitalist and other EEs are constituted at multiple spatial scales. Second, such efforts might also be advanced by deploying strategic action field theory (Fligstein and McAdam, 2011), which has become the dominant paradigm in economic sociology for understanding how different domains of economic action are nested within one another, “like Russian dolls”, and overlap with one another, as well. Although urban/regional scholars have only recently begun to spatialize field theory (Spicer and Casper-Futterman, 2020), its focus on distinct logics of action within and across fields might enable scholars to identify exactly how many EEs exist in different regions, map their relational connectedness, and determine the socio-economic consequences of such variegation, as well.

See original for full references.

Acknowledgements

The authors kindly thank Katharine Rankin and Debby Leslie for their helpful comments and feedback. They also wish to acknowledge cooperative entrepreneurs and ecosystem actors in Toronto and Montréal for providing their time and insights to us for this study.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Jason Spicer https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3286-8034

Published under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

- 1The most historically well-known was the nineteenth century's Cooperative Commonwealth strategy (Gourevitch, 2015), in which all types of cooperatives, including worker cooperatives, coordinate up and down the supply chain, through formal and informal relationships, to achieve scale and develop their operations. There are significant parallels between the Cooperative Commonwealth and cooperative ecosystem approaches (Spicer, 2020).

- 2In the diverse economic world beyond the bounds of productive enterprises (Gibson-Graham, 2006), we might expect to find recognizable ecosystem elements of some kind, as well, but we cannot speculate at this time as to whether such activities and their ecosystems might be organized into EEs, given the focus on production in the EE literature. For our purposes, entrepreneurship within the bounds of productive enterprises may still offer the opportunity to foreground non/more-than-capitalist practices, likely through IOF alternatives.

- 3Though shadow cases are occasionally deployed in urban/regional studies scholarship (e.g. Sotiropoulou, 2016), this approach is most commonly associated with comparative case study research in sociology and political science (Morgan and Prasad, 2009; Ornston and Schulze-Cleven, 2015; Thelen, 2014; Berezin, 2009), where it is well-documented as a method (Peters, 2013; Gerring and Cojocaru, 2016). Shadow cases can be useful to create a contrast/control case on background, particularly when the shadow case is well-documented or well-researched (ibid). In urban planning, this is sometimes called the "n of one plus some" (Mukhija, 2010) approach, with a primary case supplemented a secondary background case. Reliance on secondary sources for a shadow case avoids the ”research burden/fatigue” problem, in which resources of real-world actors in well-studied cases (often marginalized groups/ organizations) are strained by demands/requests placed by researchers (Huckins, 2021, Neufeld et al., 2019).

Add new comment