By Daniel A. DeCaro

Introduction

My paper focuses on the apparent discrepancy between how the science of self-governance and practitioners of self-governance seem to conceptualize participation. In particular, by drawing insight from the findings of solidarity practitioners and psychological science, I will argue that solidarity-based economies exist for reasons beyond traditionally recognized economic and informational considerations. Specifically, I argue that institutional stakeholders (e.g., consumers and producers) want to satisfy social-psychological needs?needs for social justice (living in a ?fair? world), self-determination, social belonging, and self-competence?in addition to meeting their economic needs.1,[i]

Based on this observation, I will encourage the scientific community to broaden its investigation of collective action in two important ways. First, the scientific community should more strongly consider the importance of stakeholder participation in establishing and maintaining well-functioning governance systems, no matter what the particular social-ecological context. Second, the scientific community should differentiate between categories or types of participation to better capture the nature and mechanisms of well-functioning solidarity-based economies. These categories should be identified based on stakeholders' (scientifically measurable) perceptions of what types of institutional arrangements and procedures constitute socially-just institutional decision-making procedures and the fair use of power.2

I am not the first to note the importance of attending to problems of power and types of power,3,4 or to matters of social justice in institutional analysis.5 However, I hope to clarify these issues somewhat by discussing research from social psychology (e.g., social-psychological needs, social perception and motivational processes) and social/organizational justice (e.g., procedural justice). My goal is to outline what I see as the scientific advantages of complementing the Ostrom School of institutional analysis with social-psychological and practitioner perspectives on social justice. I hope the ideas presented here will help us all continue to formulate the important questions that need to be asked about collective action.

The Differing Perceptions of Participation

The extent to which institutional stakeholders participate in their own governance is one of the most fundamental dimensions of human governance. The topic of stakeholder participation figures prominently in popular and professional discourse on civic agency, political and institutional freedom, justice, and legitimacy.6 The everyday task of navigating a world shaped by social, economic, and political power differentials - in which some individuals have power over others - makes participation central to the human institutional experience.7,8 Given such prominence, it is not surprising that the topic of stakeholder participation is central to both the solidarity economics movement and the Ostrom School of institutional analysis.

Contributors from the Ostrom Workshop collaborated in creating supplementary information to assist readers with some of the technical language, basic tools, and key concepts they work with. They include the following three sections:

At its core, solidarity economics involves grassroots economic stakeholders and practitioners (e.g., individual workers, producers, and consumers) working together to craft enduring economic organizations (e.g., community markets, worker cooperatives, and community-based natural resource conservation units) to meet their needs and the needs of the broader community through processes of democratic deliberation and co-authorship.9 With their scientific experimental and observational work on self-governance (i.e., management of institutions by the individuals affected by those institutions), the Ostrom School demonstrates empirically that these solidarity-based economies are not only possible, but also among the world's most promising alternatives to traditional state-centered, "command-and-control" economic solutions to our world's pressing social and ecological problems.10,11

This special edition of the Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter seeks to bring the activist practitioner perspective of solidarity economics into dialogue with the science of self-governance to explore what novel lessons may be learned about collective action. The GEO Collective explicitly espouses a mission to "promote an economy based on democratic participation, worker community ownership, [and] social and economic justice."12 Such advocacy implies a strong and unambiguous dedication to stakeholder participation as an indispensable element - indeed, a defining feature and motivating factor - of a well-functioning economic system.13,9 In addition, by clarifying that the type of participation sought is "democratic" and aimed towards "social justice," the GEO Collective's position also seems to imply that a certain form of participation is essential to well-functioning systems.

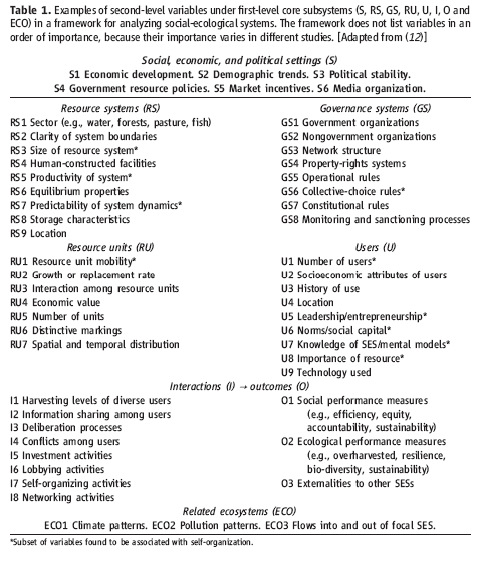

Clearly, the Ostrom School also regards stakeholder participation as important. The school of thought identifies the involvement of stakeholders in institutional management as an important factor in determining whether institutions will be effective and enduring (see Table 1).10 However, unlike the solidarity economics movement, the Ostrom School conceptualizes the benefit of participation primarily in terms of its informational and problem-solving value. Specifically, it is believed that the process of participation reveals information about the actions and intentions of other economic agents. This information contributes to coordination and trust-building by reducing uncertainty about what others will do.14 Moreover, it is believed that the local knowledge provided by grassroots-level participation can lead to better-informed institutional designs and economic solutions for grassroots-level problems.9,11,15

Table 1. Critical Factors of Long-Enduring Social-Ecological Systems

Sources: From E. Ostrom. (2009, July). A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science, 325, 419-422. http://www.sciencemag.org/content/325/5939/419.abstract. And from E. Ostrom (2007). A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(39), 15181-15187. Reprinted with permission from AAAS and PNAS.

According to this informational and problem-solving perspective of participation, different social-ecological situations pose different informational and technical challenges. As such, participatory approaches are thought to be best suited for some problems, while traditional non-participatory economic approaches are thought to be best suited for others.16 In this sense, the concept of participation within the Ostrom School of thought is treated as one potentially important factor among many (See Table 1). In addition, though self-governance implies that institutional stakeholders have ownership and involvement in management of some kind, the Ostrom School does not explicitly distinguish between different categories or types of participation; it also does not base its technical concept of participation in notions of "democracy" and "social justice."[ii]

In the discussion that follows, I clarify and address this apparent discrepancy between how the science of self-governance and practitioners of self-governance seem to conceptualize participation. In doing so, I argue for a broader conceptualization of power within the Ostrom School of institutional analysis - one which grounds participation in psychological science principles of social-psychological needs and measurable dimensions of social justice.

The IAD Framework, Participation, Power, and Social Justice

The Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) Framework is a tool that helps institutional analysts within the Ostrom tradition systematically evaluate governance systems to reveal underlying sources of institutional success and failure.17 Institutional analysis within the IAD Framework starts with the action situation, which is the immediate social context within which focal stakeholders behave (see Figure 1).18 In any given decision situation, actors possess certain social roles (e.g., boss and employee), which identify for those people what is appropriate or permissible to do, as defined by established rules and norms. The IAD framework guides theorists in systematically identifying the social and ecological dimensions (e.g., characteristics of governance systems, actors, and economic and natural resource systems) that shape a particular action situation and influence people's behaviors and, ultimately, the effectiveness of the institutions themselves.[iii]

Figure 1. Action Situation: Rule Structures

Source: From E. Ostrom. (2005). Understanding Institutional Diversity, (p. 189). NJ: Princeton University Press. Reprinted with permission from Princeton University Press.

For example, in her groundbreaking work, Elinor Ostrom (1990) used the IAD framework to analyze the social and ecological factors that structure and influence enduring common-pool natural resource management institutions at the grassroots level all around the world (see Table 1). It is based on this conceptual and technological advancement that the Ostrom School demonstrated that solidarity-based economies offer promising alternatives to traditional state-centered economic solutions to our world's social-ecological problems.11

Despite its impressive ability to explain institutional success and failure, the IAD Framework has been criticized as not paying enough attention to specific nuances within participatory situations - problems of power related to social justice (e.g., Clement, 2010).3 It is my opinion that a clearer conceptualization of power and its role in determining stakeholder perceptions of social justice within institutional settings will broaden the ability of the IAD framework to predict institutional success. A clearer treatment of power and social justice may also help further connect the findings of practitioners with the scientific theories intended to explain them.

Specifically, I argue that solidarity-based economies exist for reasons beyond traditionally-recognized economic considerations - namely, that stakeholders want to satisfy social-psychological needs for justice (living in a "fair" world), self-determination, social belonging, and self-competence.1,[iv] Furthermore, stakeholders' pursuit of these needs helps explain why solidarity-based economies emerge, while the way different types of institutional arrangements differentially satisfy these needs helps explain when and how institutional arrangements function well.

Conceptualizing Power

At the most abstract level, power can be conceptualized as the influence people have on each other to shape each others' perceptions, aspirations, and decision-making options through their own behaviors, roles, and the creation of rules and norms.19 Within the IAD Framework, such power as influence is represented by the social interactions - specifically, social roles and the rules and norms associated with them - that create particular action situations (see Figure 1). Recall that in any given decision situation, actors possess certain social roles (e.g., boss and employee), which identify for those people what is appropriate or permissible to do, as defined by established rules and norms. Indeed, the IAD Framework's ability to help analysts catalogue these interconnections of influence is, perhaps, its primary strength.

Another way that the Ostrom School addresses power relations is in terms of the concept of self-governance. Within the IAD framework, self-governance is seen as empowering the individual. Individuals are given the ability to participate in their own governance, and therefore have "power with" one another to determine their own fate.4

Although the IAD Framework acknowledges the role that power and participation have in a given institution (i.e., "power-with"), the distinction essentially is binary. That is, grassroots-level institutional stakeholders are treated as either self-governing or not. In particular, analysts using the IAD framework document this aspect of power in terms of whether or not "most individuals affected by a resource regime are authorized to participate in making and modifying rules" (E. Ostrom, 2010, p. 653).11

Recently, the IAD Framework has been criticized as not paying enough attention to power (e.g., Clement, 2010). I suggest that critics and proponents of the IAD Framework are arguing over the different conceptualizations of power - power as influence versus power-with. I also suggest that the IAD does an excellent job addressing power as influence, but could be strengthened with regard to its treatment of power-with. Recognizing this point may allow theorists to explain a broader set of institutional problems, as well as better capture the motives and institutional dynamics underlying self-governance and solidarity-based economies.

Different Ways of Having Power-With

One key problem with conceptualizing power-with in a binary fashion (i.e., as either present or absent in a given institutional setting) is that some "participatory" situations may only be participatory on the surface. For example, as noted by Clement (2010), there is a tendency for national governments to authorize grassroots policy stakeholders to participate in making and modifying rules, but through specific mechanisms that do not give stakeholders significant institutional decision-making control.[v] Another problem with conceptualizing power-with in a binary fashion is that some ways of participating may be more "participatory" than others and, therefore, yield different results. For example, even among self-governing grassroots collectives, stakeholders can organize themselves in ways such that, while all are present and "participating," most lack what they would consider genuine institutional voice and choice.1 But nuances in ways of participating may go unaccounted for by practitioners or scientists when participation is treated as a binary concept. Thus, just as the GEO Collective is careful to define participation specifically as "democratic" and aimed towards "social justice" - implying a certain way of doing things - theorists such as Clement (2010) and myself (e.g., DeCaro & Stokes, 2008) seem to want to differentiate between specific ways of having influence and power-with.

I suggest that the distinction between different types of participation could be better formalized with the help of concepts from Self-Determination Theory20,21, which is a framework of motivation and behavior from social psychology. Self-Determination Theory describes organizational settings as either coercive or autonomy-supportive depending on whether or not the institutional management procedures used support individual social-psychological needs (e.g., self-determination and social justice).[vi] According to Self-Determination Theory, institutional settings may be considered coercive when agents pressure others towards specific goals, and ways of achieving those goals, especially through threats, punishments, economic manipulation and restrictive forms of institutional decision-making. In contrast, autonomy-support refers to when individuals are encouraged to adopt ideas and behaviors without the use of such pressure, manipulation, or restriction.22 What is considered coercive or autonomy-supportive to particular individuals (e.g., getting to vote versus being told what to do by a legitimate authority figure) may depend on the particular cultural setting.23 Moreover, research demonstrates that autonomy-supportive institutional procedures tend to be perceived as procedurally-just or fair.24 Thus, although various cultural and institutional sometimes "disagree" on what constitutes coercion, they nevertheless systematically distinguish between autonomy-supportive and coercive ways of influencing others and participating, or having power-with other institutional stakeholders.[vii]

The implication is that, even when "most individuals affected by a resource regime are authorized to participate in making and modifying rules" (i.e., when individuals are self-governing), these individuals could still experience coercion, depending on exactly how they self-govern. For example, the type of voting procedures used or not used, and the types of punishments or other incentives used, all potentially could impact whether self-governance is coercive or autonomy-supportive in nature.1 Thus, I would argue that, whereas the Ostrom School conceptualizes power in the more neutral or agnostic sense of "influence" and conceptualizes participation, or self-governance, in a binary sense, solidarity economies, the GEO Collective, Clement (2010) and others (e.g., DeCaro & Stokes, 2008) wish to make a further distinction between coercive versus autonomy-supportive ways of self-governing and having power-with each other.

Members of the Kasigau Basket Weavers Cooperative, in Kasigau, Kenya celebrate livelihoods supported by selling hand-made baskets from their grassroots economic organization. The proceeds earned from these baskets already have funded several community-development projects (e.g., an orphanage and community library) and provide much-needed income for individual households. Institutional analysts need to pay closer attention to stakeholders? perceptions to understand what motivates and sustains such economic endeavors.

Implications and Recommendations

To better incorporate notions of social justice in the Ostrom School of thought, I recommend analysts think in terms of psychological science principles of procedural justice and autonomy-support when using the IAD Framework to examine power dynamics (cf. Clement, 2010). In particular, I encourage analysts to consider the possibility that rules (see Figure 1) shape action situations and stakeholders' behaviors differently depending on whether those rules are coercive or autonomy-supportive in what behaviors they permit, the specific institutional decision-making procedures used to devise them, and how they are implemented or enforced.1 Doing so may better account for institutional situations identified by Clement (2010) as being superficially self-governing. Doing so also may better distinguish between different ways of self-governing. Ultimately, such conceptual improvements may increase the IAD Framework's analytical power and its relevance to grassroots-level practitioners.

Such an approach may also provide a more nuanced understanding of collective action. For example, the Ostrom School currently is wrestling with some fundamental questions about the emergence of self-governance: Given that it is effortful and challenging, why do people want to self-govern?11,15 The answer may be that, compared to traditional state-centered, non-participatory governance, self-governance better satisfies social-psychological needs for procedural justice, self-determination, belonging, and competence, motivating individuals to pursue self-governance.1 Indeed, the GEO Collective's mission to promote not only economic justice, but also democratic participation and social justice seem to support this point.9,13 We are currently investigating this possibility in ongoing laboratory- and field-based experiments at the Ostrom Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis.25,26

My advice to add such a social justice perspective to the IAD analytical toolkit is motivated by the empirically-informed belief that individuals naturally perceive and respond to institutional situations - rules and decision-making procedures - in terms of procedural justice and autonomy-support. Considerable evidence within organizational27 and social psychology28,20, social justice research29, and behavioral economics30 demonstrates that the use of coercion tends to degrade institutional trust31 while undermining voluntary rule compliance32, organizational citizenship behaviors such as helping and self-sacrifice5, and task persistence and performance. Thus, in my mind, the potential benefits engendered by autonomy-supportive participatory institutional contexts warrant serious consideration of such genuinely participatory approaches as essential to well-functioning institutions - that is, regardless of other social and ecological considerations.[viii] Indeed, stakeholders may be superiorly equipped - motivated, committed, and cognitively engaged - in genuinely participatory, or autonomy-supportive, institutional contexts.1

Moving Forward

This special edition of the GEO Newsletter seeks to bring the dialogues of solidarity economics, practitioners, and the science of self-governance together to explore what may be learned about the theory, research, and practice of collective action. Examining the principle of stakeholder participation, I have suggested that one area that especially needs attention is the question of what motivates self-governance and why solidarity-based economies emerge in the first place. And, I recommended the scientific community consider how stakeholders perceive and respond to participation, specifically defined as coercion and autonomy-support.

Members of the Kasigau Basket Weavers Cooperative, in Kasigau, Kenya celebrate livelihoods supported by selling hand-made baskets from their grassroots economic organization. The proceeds earned from these baskets already have funded several community-development projects (e.g., an orphanage and community library) and provide much-needed income for individual households. Institutional analysts need to pay closer attention to stakeholders - perceptions to understand what motivates and sustains such economic endeavors.

GEO and other contributors to the solidarity economic movement have a rich narrative explaining their involvement in self-governing systems (e.g., Lappé, GEO 307; Miller, GEO 35). The scientific community could learn a lot about what motivates self-governance, and about collective action more broadly, simply by devoting serious attention to, and methodological devotion towards studying, that narrative of freedom, justice, and social-psychological well-being. There also is considerable room for stakeholders, such as members of the GEO Collective, to help guide future research by contributing to theory, research design and evaluation, as well as data collection in solidarity-based economies. Together, we may be able to create a more just, economically viable, and psychologically satisfying economic world.

The permanent link to this article is http://geo.coop/node/651

About the author

Daniel A. DeCaro, PhD, is a Postdoctoral Researcher and Visiting Scholar at the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Indiana University, Bloomington. He can be contacted at ddecaro@indiana.edu.

Daniel A. DeCaro, PhD, is a Postdoctoral Researcher and Visiting Scholar at the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Indiana University, Bloomington. He can be contacted at ddecaro@indiana.edu.

Citations

When citing this article, please use the following format:

Daniel A. DeCaro (2011). Considering a Broader View of Power, Participation, and Social Justice in the Ostrom Institutional Analysis Framework.

Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter, Volume 2, Issue 9.

http://geo.coop/node/651

References

- DeCaro, D. A., & Stokes, M. (2008). Social-psychological principles of community-based conservation and conservancy motivation: Attaining goals within an autonomy-supportive environment. Conservation Biology, 22(6), 1443-1451.

- DeCaro, D. A. (2010). The promise and challenge of applying community psychology's praxis of empowerment to the burgeoning field of community-based conservation. In N. Lange & M. Wagner (Eds.), Community Psychology: New Developments, (pp. 143-160). New York: Nova Publishers, Inc.

- Clement, F. (2010). Analysing decentralised natural resource governance: Proposition for a "politicised" institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Sciences, 43(2), 129-156.

- Ostrom, V. (1980). Artisanship and artifact. Public Administration Review, 40(4), 309-317.

- De Cremer, D., & Tyler, T.R. (2005). The effects of trust and procedural justice on cooperation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 639-649.

- Tyler, T.R. (1998). What is procedural justice? Criteria used by citizens to assess the fairness of legal procedures. Law and Society Review, 22(1), 103-136.

- Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Plenum, NY.

- Nelson, G. & Prilleltensky, I. (2005). Community Psychology: In Pursuit of Liberation and Well-being. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Miller, E. Other Economies are Possible!: Building a Solidarity Economy. GEO Newsletter, Node 35. http://www.geo.coop/node/35. Accessed online April 22, 2011.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2010). Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. American Economic Review, 100, 641-672.

- About GEO, Grassroots Economic Organizing. http://www.geo.coop/about, accessed online April 22, 2011.

- Lappé, F. M. Why are we playing Monopoly when we could be playing democracy? GEO Newsletter, Node 307. http://www.geo.coop/node/307. Accessed online April 22, 2011.

- Ostrom, E., Walker, J., & Gardner, R. (1992). Covenants with and without a sword: Self-Governance is possible. American Political Science Review, 86(2), 404-417.

- Poteete, A. R., Janssen, M. A., & Ostrom, E. (2010). Pushing the frontiers of the theory of collective action and the commons. In A.R. Poteete, M. A. Janssen, & E. Ostrom (Eds), Working Together: Collective Action, the Commons, and Multiple Methods in Practice, (pp.217-287). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ostrom, E., Janssen, M. A., & Anderies, J. M. (2007). Going beyond panaceas. PNAS, 104(39), 15176-15178.

- McGinnis, M. D. (2011). An introduction to IAD and the language of the Ostrom Workshop: A simple guide to a complex framework. Policy Studies Journal, 39 (1), 163-177.

- Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding Institutional Diversity. NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Isaac, J. C. (1987). Beyond the three faces of power: A realistic critique. Polity, 20(1), 4-31.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-Determination Theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology 49(3), 182-185.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life's domains. Canadian Psychology, 49(1), 14-23.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(4), 1024-1037.

- Ryan, R. M, & Deci, E. L. (2006). Self-regulation and the problem of human autonomy: Does psychology need choice, self-determination, and will? Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1557-1585.

- van Prooijen, J.-W. (2009). Procedural justice as autonomy regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(6), 1166-1180.

- DeCaro, D. A. (2010, December). Participatory inclusion in management as the means and ends to sustainable self-governance. Paper presented at the annual Mini-Conference, Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Bloomington, IN.

- DeCaro, D. A., Ostrom, E., & Walker, J. (2011). What Motivates and Sustains Voluntary Rule Compliance? Towards a Psychological Framework of Self-Governance in the Commons. Grant Proposal.

- Greenberg, J. (1990). Organizational justice: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Journal of Management, 16(2), 399-432

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The "what" and "why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227-268.

- Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386-400.

- Frey, B. S., Benz, M., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Introducing procedural utility: Not only what, but also how matters. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 160, 377-401.

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331-362.

- Moller, A. C., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Self-Determination Theory and public policy: Improving the quality of consumer decisions without using coercion. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 25(1), 104-116

Endnotes

[i] Let me briefly explain my citation style. All of my references are numbered, 1 through 32. Each time "1" appears as a superscript in the body, it is referring to DeCaro & Stokes (2008), which is numbered 1 in the list of references. Likewise, when superscript "32" appears in the body of the paper, it is referring to Moller et al., which is numbered 32 in the list of references.

Roman numerals indicate endnotes like this one, which are devoted to parenthetical statements, such as clarification statements and places to look for additional readings (note that an additional reading is not the same thing as a citation).

[ii] Though see V. Ostrom (1980). Artisanship and artifact. Public Administration Review, 40(4), 309-317.

[iii] For another related framework from the Ostrom School (i.e., the Social-Ecological Systems Framework), see: Ostrom, E. (2009). A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science, 325, 419-422.

[iv] For an interesting discussion of the role these social-psychological needs may play in broader public policy, see: Moller, A. C., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Self-Determination Theory and public policy: Improving the quality of consumer decisions without using coercion. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 25(1), 104-116.

[v] For examples and further discussion on this point, interested readers may also wish to see: Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35, 216-224; and Bloomquist, W., Dinar, A., & Kemper, K. E. (2010). A framework for institutional analysis of decentralization reforms in natural resource management. Society & Natural Resources, 23(7), 620-635.

[vi] At the time of this writing, the link made here between autonomy-support and perceptions of social justice has not been formally recognized within Self-Determination Theory - it is my own observation based on: van Prooijen, J.-W. (2009). Procedural justice as autonomy regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(6), 1166-1180.

[vii] For lists and explanations of what kinds of institutional management procedures have been shown through science to (typically) be perceived by institutional stakeholders as coercive or autonomy-supportive, see: Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386-400. Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C. (2008). The effects of choice on intrinsic motivation and related outcomes: A meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 270-300. Ryan, Mims, & Koestner. (1983). Relation of reward contingency and interpersonal context to intrinsic motivation: A review and test using cognitive evaluation theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(4), 736-750.

[viii] This is not to say that the specific instantiation of such participation should be the same across social-ecological situations or that participation will always be successful or able to overcome all obstacles alone.

Add new comment