The Cooperative Approach to the Home Care Crisis

The home care crisis isn’t new, but it is receiving renewed attention that provides an opportunity to address some of the longstanding challenges this critical sector faces. There is a shortage in direct care providers—in part because of the growing number of people needing care, but also because the jobs are incredibly challenging, undervalued and underpaid. In several communities across the country, home care workers have come together to form worker cooperatives. As a co-op, home care providers own and control their businesses and experience lower workforce turnover, leading to more highly-trained workers and higher quality care.

Moderated by NCBA CLUSA Director of Government Relations Kate LaTour, “Bringing Dignity to Caregiving: The Cooperative Approach to the Home Care Crisis” will feature the following speakers:

Terrell Cannon, Director of Training and Workforce Development, Home Care Associates

Deborah Craig, Cooperative Development Specialist, Northwest Cooperative Development Center

Nora Edge, Executive Director, Capital Homecare Cooperative

Katrina Kazda, Program Director for Home Care, The ICA Group

Kezia Scales, Director of Policy Research, PHI

Jonathan Ward, Director of Lending, Fund for Jobs Worth Owning

Transcript (begins at 01:58)

John Torres: Good afternoon, folks. I am John Torres with NCBA CLUSA. And welcome to today's webinar entitled "Bringing Dignity to Caregiving: The Cooperative Approach to the Home Care Crisis.”

With a growing number of people needing care, there is renewed attention on this subject, which provides an opportunity to address some of the longstanding challenges this critical sector faces. So just before we get started, I have a few housekeeping items. Today's webinar is scheduled for seventy five minutes. There will be specific times when questions will be answered and addressed. And so to add your question, please go to the Q&A section of your GoToWebinar control panel and add your question there.

This meeting is also being recorded and we will share this recording link to all those who have registered for this webinar after today's meeting now without any more delay. We will pass this right along to NCBA CLUSA's Director of Advocacy, Kate LaTour. Hi, Kate.

Kate LaTour: Hi, John, thank you so much. Thanks for all the support in making this conversation possible today. And again, thank you to Tilde Co-op for joining us, and to the Cooperative Development Foundation for their support.

As John mentioned, today's conversation is really timely and is jam packed with some incredible folks. So I'll be very brief. We wanted to bring together our panelists to help understand the challenges and opportunities within the home care sector broadly, as well as within that sector, understanding the cooperative difference. There are several driving forces that are really pushing this conversation forward. And like I said, I'm going to leave that to our experts today to dig deeper into that. But it really is a moment for home care co-ops to play the role that co-ops do so well as a community driven, people powered solution to this mounting challenge. In home care co-ops may not be the single policy solution to fix the sector, but it is critical that policies are inclusive of co-ops and that policymakers lean in and depend on co-ops for this purpose. Co-ops in this sector especially, are great examples of how co-ops fundamentally behave differently than other business models, from workforce development to quality of care because workers are the owners.

So to give an overview of how today's conversation will go first, we will hear from Dr. Kezia Scales, director of policy research at PHI, on the current health care landscape and why this is such a pivotal moment. Then, Katrina Kazda from the ICA Group and Jonathan Ward from the Fund for Jobs Worth Owning will hone in on some of those specific policies to building more cooperatives in the home care sector, particularly focusing on technical assistance and financing. And we'll close out the conversation with a conversation led by Deborah Craig, cooperative development specialist at the Northwest Cooperative Development Center in Olympia, Washington, alongside two home care co-op owners, Nora Edge, executive director of Capital Home Care Cooperative in Olympia, and Terrell Cannon, director of training and workforce development at Home Care Associates in Philadelphia. So, as John mentioned, we have budgeted time for questions and answers, so please feel free to type those in on a rolling basis. We will get to as many as we can in today's conversation, and anything we don't get to, we'll do our best to include responses to them in the wrap up materials that we send out next week. So without further ado, I'm happy to turn things over to Dr. Kezia Scales from PHI.

Kezia Scales: Thank you so much. Can you hear me? Well, thank you. Thank you for the opportunity to contribute to this important discussion. I'm the director of policy research for PHI, as Kate mentioned. PHI is a national nonprofit organization that's dedicated to promoting quality direct care jobs as the foundation of quality care. We address the quality of direct care jobs through a range of interventions, from workforce development efforts on the ground alongside workers and their employers, to research policy, advocacy and public education to enact systems level and structural change. Its core training and employment model is anchored in our longstanding work with Cooperative Home Care Associates, or CHCA, which is a worker-owned home care agency that employs more than two thousand New Yorkers. CHCA was formed in 1985, and it's the country's largest worker-owned cooperative business. Together, PHI and CHCA acheive field leading outcomes in home care, training and employment. Thanks to our adult learner centered approach to training, the provision of wrap-around benefits and supports, and the centering of workers and everything that we do. Next slide please, and then one more slide ahead. Thank you very much.

So I want to set the stage for why we're talking about a home care crisis and why now is the moment to really address and overcome this crisis. When we talk about the home care crisis, we're really talking about the home care workforce crisis, because it's the high turnover and job vacancy rates within the home care workforce that are impeding the sector's ability to keep up with the growing need for home and community-based long term care services.

So who are homecare workers? There are 2.4 Million frontline paid caregivers, officially classified as personal care aides and home health aides, but known in practice by a range of job titles. And these workers support older adults and people with disabilities in private homes and community settings across the United States. This workforce is predominantly women and people of color, and nearly one in three home care workers was born outside the United States. The median age for health care workers is 47, and a full third of the workforce is aged 50 and above. Considering this demographic snapshot, these are workers who in many cases face intersecting structural inequities in education and employment, and in many other ways. Homecare workers provide essential support with daily activities from personal care, to housekeeping, to shopping and managing appointments, and much more. And depending on their training, certification and job role, they may also provide clinical services and supports. And everything that they do is underpinned and sustained by the personal relationships that they establish with their clients. Next slide, please.

And I just quickly want to share a quote from a home health aide in New Jersey that exemplifies the relational nature of this work and how important that is. Maria says, "My clients are very special to me. From the first day I meet them. They're not only my clients, but they're part of my family. Many of them don't have any other help and might be alone at home the entire week, except for when an aide is there. They're happy to see me and usually a couple of minutes after I arrived, they're already smiling. That's a beautiful gift you get being a home care aide.". Next slide, please.

So the home care workforce is large, 2.4 Million workers and growing rapidly in response to skyrocketing demand for home and community based services. That demand is driven, of course, by the aging of our population, by the fact that people are living longer with complex conditions, because people prefer to age and receive services in place, and the policy landscape is shifting accordingly. And because there are fewer family caregivers available than in previous generations, these have been driving factors for years, as illustrated by the graph here on the side of the slide, which shows that Home Care added 22,000 new business establishments between 2007 and 2017, which is the most recent year of data that we have. And that was the lion's share. 64% of all long term care business growth, when thinking also about residential care settings, like assisted living and nursing home settings as well. And we will only see an acceleration of that trend in the aftermath of Covid-19 as even more services shift from acute and post acute settings, and from nursing homes to the community

So, in terms of workforce numbers, what that means is that home care added 1.4 million new jobs in the last decade, and the workforce is expected to add more than a million more in the decade ahead. That's more new jobs than any other US occupation. And when you take job separations into account as well, meaning when existing positions become vacant because someone leaves the occupation or leaves the labor force altogether, we will need to fill nearly five million total job openings in that same time period during the next decade. Next slide, please.

But the problem is that these are not, for the most part, high quality jobs. And I want to take a moment just to say that when I'm talking about here are the systemic, the structural conditions, that define these jobs: the laws and regulations and financing mechanisms that create the conditions in which home care employers operate. So I'm talking about the system, and then we'll be talking about what's possible at the provider or the employer level within the system.

So these are not, for the most part, high quality jobs. Median wages for homecare workers are just over 12 dollars an hour and median earnings are only about $17,000 a year. As a result, nearly half of this workforce lives in or near poverty, and more than half relies on public assistance to make ends meet. Homecare workers also receive limited entry level and ongoing training. They enjoy few opportunities to advance in their careers, and their hard work is so often overlooked and undervalued. So recruitment and retention have been huge challenges in the home care sector for a long, long time. But the workforce crisis has perhaps never been more pressing than it is now, given the disproportionate risks and responsibilities that were shouldered by home care workers during the Covid-19 pandemic. Given the lack of support for these workers during the past year, in terms of access to PPE, hazard pay, paid leave and so on. Given the volume of workers who had to leave their jobs due to illness or family responsibilities or for other reasons, these immediate factors are making it even more difficult to recruit new job candidates to this sector. And that means evergrowing unmet needs for services among older adults and people with disabilities. Next slide, please.

Here's another quote from a home health aide in Brooklyn, New York, that exemplifies how difficult it is to make a living as a home care worker, Farah says, "As home health aides, we work too hard. We're dealing with too much stress with the clients. And we also have to deal with family members and we're not getting paid for how hard we work. That's the problem. You have to pay your bills. You have to take care of your family. And if you're working hard six to seven days a week and you still can't cover your bills, then why are you working?" This quote to me illustrates why we need to raise the floor on these jobs and make them viable, make them jobs that people want to do and can sustain. Next slide, please.

And the moment to make that meaningful change is now. Caregiving has finally been recognized as part of our nation's infrastructure, just as essential for our productivity and our success as bridges and buildings and broadband. Here's what President Biden said when releasing the American jobs plan last month. He said, "Ask Americans what sort of infrastructure they need to build a little better life, to be able to breathe a little bit. It's home care workers who go in and cook their meal, help them get around and live independently in their home, allowing them to stay in their homes and I might add, saving Medicaid hundreds of millions of dollars in the process. It's better wages and benefits and opportunities for caregivers who are disproportionately women, women of color and immigrants. So the American jobs plan proposes a historic $400 billion investment in expanding home and community based services and improving jobs for home care workers. This level of recognition and investment could be transformational for the sector and its workforce." Next slide, please.

And alongside the American Jobs Plan is a whole raft of other proposals and bills at the federal level that will or could also directly impact the home care sector, improve home care jobs and help stabilize this workforce, not least the American Rescue Plan, the American Families Plan, the US Citizenship Act, and several bills that are specifically aimed at direct care workers, including the Direct Care Opportunity Act and this Workforce Advancement Act. In the interest of time, I won't talk through the relevance of each of these bills, but the list overall gives a sense of how the structures in which home care providers operate, including worker-owned cooperatives, are shifting and changing and opening up new opportunities. And we're also seeing unprecedented attention on this workforce at the state level, with states establishing work groups and task forces considering different strategies to raise wages for home care workers and other direct care workers, exploring new recruitment pipelines and career pathways in the sector, and much more. So this is home care's moment, because the need is so great, the challenges are so evident and there are strategies and solutions on the table. Next and final slide, please.

As we're talking about how to realize the potential of this moment, I just want to stress the importance of thinking holistically about home care job quality: at the structural level, the policy level, and also at the provider level, the practice level. At PHI we talk about the five pillars of job quality for these workers and what this framework shows is that, yes, we absolutely need to improve compensation, including wages and benefits, but we also need to make sure that home care workers receive sufficient training to do their jobs well. That they receive the supervision and support that they need to succeed, that they're respected and recognized for their essential contribution, and that they have real opportunities to grow and develop and advance in their careers. Home care cooperatives are uniquely positioned to lead the field in creating and sustaining high quality jobs for home care workers across these pillars, given the alignment between the interests of workers, workers as owners and clients, and given the current energy around addressing the home care crisis at this moment. So on that note, I'm happy to hand it over to my colleagues on the panel to say more.

Kate LaTour: Thank you so much, Kezia. That was just an excellent overview. I know I personally have several threads I'm looking forward to pulling on during the Q&A session. But for now, we are going to turn to Katrina and Jonathan, who are going to focus in a little bit more specifically on co-ops. And so, Katrina, I think you are kicking things off.

Katrina Kazda: I am, thank you. Thanks, everyone, and really an honor to be here. If you could go ahead and move into the first slide and actually you can just keep going from there. Do one more. All right. Great. Thank you.

Well, so I'm Katrina Kazda. I'm the director of the Home Care Program at the ICA Group. The ICA Group is a national nonprofit organization with the mission to advance businesses and institutions that center worker voice, real worker wealth, and build worker power. ICA has a really long history in the home care cooperative sector. Beginning in 1985 with the launch of Cooperative Home Care Associates, who Kezia mentioned, they were the first worker-owned home care company in the United States. And today they're also the largest worker-owned home care company, and the largest worker-owned company of any industry.

So ICA's work in the home care space is really both broad and deep and is really organized around two core goals. The first is really around building and coordinating national networks of home care cooperatives with the goal of really strengthening the sector and collectively pushing innovation both in the cooperative sector specifically, but also really in the home care industry broadly. We're always trying to to push the limits on what is possible. Working together over the past six or so years, we've really been enhancing national collaboration, doing peer exchange, peer learning. We have an annual conference, we've done group purchasing and we're really working to enhance that collaboration now, in more formal and institutionalized ways that will be excited to talk about in the future. Additionally, we're constantly pushing on scaling of worker ownership in the home care industry, really through innovative game changing approaches, including large scale public private partnerships.

One important example is the Trust for Workers, which is a joint venture in Washington state between the state or private entity, and the union. And when that officially rolls out the new entity, the trusts will employ nearly forty thousand caregivers in a worker-centered employment model. So we're really excited about that and look forward to talking about that more soon, as well. Next slide.

So when we talk about the home care cooperative sector, what we are talking about is a national network of 14 operational home care cooperatives, worker-owned companies in nine states, which employ over 2800 workers, roughly 50 percent of which are also owners of their companies. There's at least a half a dozen new cooperatives that are under development today as well. And we're just seeing more and more interest in the model as the benefits of it are really starting to get out into the industry.

For the last three years, we've run a national benchmarking survey annually. I think intuitively we have always thought and known that the cooperative model offered higher quality jobs and higher quality care. But we had really lacked the data to demonstrate that. So we launched this benchmarking study three years ago now and we'll do our fourth round this year. And it's been incredible just being able to really see the proof of the benefits of the model. And I'm going to share some of those data points with you now. Next slide.

So first, this is from the 2019 study, we found that on average home care cooperatives pay a $1.93 More per hour than non-cooperative agency peers in their state. In a low wage industry like home care it really goes without saying that nearly a two dollar difference per hour in pay is very significant. And this is something we're certainly incredibly proud of as a sector. I will also say on the flip side, being such a low wage industry, two dollars an hour additional really doesn't change the game. It does not make home care really a viable profession for most individuals, in particular if you're supporting a family. So this is a huge achievement given the broader context of the home care industry in the home care market that cooperatives are operating in, but really is just the beginning of what we hope to achieve, certainly in this sector. Next slide.

Our survey also found that 90 percent of home care cooperatives go above and beyond state minimum required caregiver training. So this really demonstrates the investment in caregivers success on the job. You know, caregiving is actually extremely difficult job, even though it's often labeled as unskilled or not thought of as such. But it really does require a lot of skill and a lot of intuition. And so this investment by cooperatives in their caregivers to really succeed in the job is very significant. Ninety percent of cooperatives provide opportunities for speaking engagements and advocacy work, and this is another incredible benefit.

I will never forget speaking with one of home care associates, long time caregivers -- I think she's been with the cooperative for twenty five years now and has been involved in the Cooperative Advocacy Committee -- and has spoke about how life changing it has been for her to advocate for home care workers, and really represent workers in the political space. So it's a great opportunity and really speaks to sort of this investment writ large in home care workers. And 90 percent of cooperatives provide opportunities to work in the office and develop administrative skills. And again, this is really important. There's not a lot of career ladders or opportunity for caregivers within the home care space. And many caregivers love caregiving and have no desire to change their position. But for those that do, there need to be career ladders within the industry rather than out of the industry, which is most common today.

So this is really just a small sampling of the different ways that home care cooperatives really wrap around their caregivers, their workers, and provide opportunity and invest in them to really make caregiving a viable and exciting profession. Next slide.

And so the result of this is really that home care cooperatives outperform the industry year over year in caregiver turnover. So caregiver turnover is a huge problem in the industry. There's there's both a shortage of caregivers in in the field, and then a huge problem with caregivers churning between agencies or leaving the industry altogether just given the employment conditions. So. In 2018 home care cooperatives average a caregiver turnover rate of 30 percent, compared to 82 percent in the broader industry, and in 2019 they remained pretty steady at about 40 percent, while the industry actually did see a pretty significant drop to sixty four percent, which is a positive trend. I think that really reflects the awakening of the larger home care industry about the importance of caregivers. Without caregivers, there is no home care industry, and so agencies in this environment of caregiver shortage are starting to make greater investments. And that's a positive trend. That year over year, cooperatives have made these investments and have always led in turnover rates, again, something we're quite proud of. Next slide.

So why caregiver turnover matters -- this is something that Kesia really spoke to -- is that the best measure of quality care is really the quality of the relationship between the caregiver and the client. And I think we all know relationships are built with time. So you need that consistency. You need that caregiver to be showing up day in, day out, to serve a client, to be able to build that relationship, that trust out of which comes communication and then that quality really flows. So with the low turnover rates that caregiver cooperatives have been able to to demonstrate, they are really in a better position to deliver on this quality of care, to be able to deliver on this relationship that's really needed to to maintain high quality of life, and high outcomes for clients. Next slide.

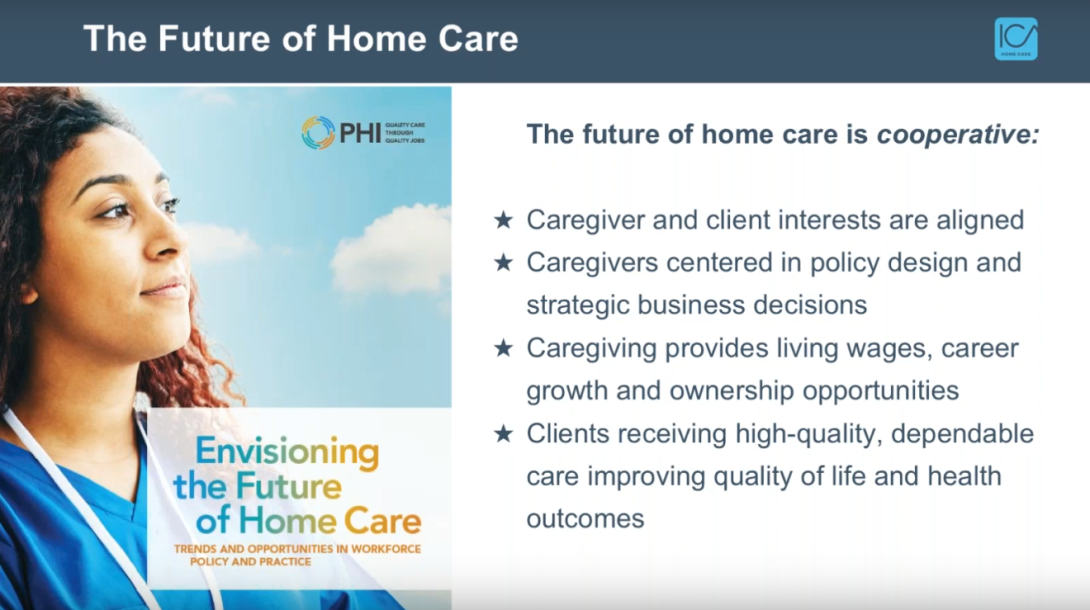

So looking ahead, you know, we really envision in the cooperative sector a very different future for home care and caregiving, one that's not just marginally better and where pay is slightly better, where we're really needing a minimum, but where caregiving is actually a desirable and viable profession, one where young people would look at caregiving as a viable option for a career, where they could enter and grow and really feel the rewards of their hard work. And of course, we see cooperatives as a central element of that future. You know, we really have a unique opportunity in this moment with the investments that are being talked about in the home care industry to not only set the floor, which is a wonderful achievement, but really to build the ceiling and really think about a new and different future. And an investment is going to be needed to really make that possible; both investment in the workers, and also investments in new and different models that center workers, and really change the nature of how money flows, and how rewards flow in the home care industry right now. When we look at this future, that's kind of cooperative, worker-centered future of caregiving, we really imagine a world in which caregiver and client interests are aligned as sort of a key feature of the cooperative model. When your caregivers are also your shareholders, there's not this conflict between profit and quality, which is ever present in the home care industry right now.

Home care workers are on the front lines. They're the ones doing the work, seeing the problems. And so centering those voices in policy, design, and business decisions really changes the game and is the way that we need to be thinking about the future of the industry. Of course, we envision, as I said, a world in which good wages are possible, not just standard wages that are really subpar, where career growth and ownership is really central. I didn't mention this before, but 100% of cooperatives offer ownership opportunities: that is the central point of cooperatives. And so being able to be a part-owner of the place that you work, that is just a very unique opportunity that very few caregivers have at this moment. And we'd really like that to be the majority, rather than the minority. And of course, in this system that we envision, and that we know is already happening at the smaller level, clients are really receiving this higher level quality of care. It's dependable, their quality of life is better, and the ripple effects of those positive impacts are really broad: at the individual level, the family level, the community level, the health system level and really the broader society. So there's kind of no end to the benefits and opportunities that we see present if we make the right investments. So thank you. That's all I have to say for now. And I just really appreciate this opportunity to to share a little bit about the cooperative sector. Thank you.

Kate LaTour: Thank you, Katrina. Thank you, Jonathan, for coming on. We're going to transition right into Jonathan's presentation from the Fund for Jobs Worth Owning.

Jonathan Ward: Thanks, everyone. Good to be here with you in this moment. I'm Jonathan Ward, director of lending at the Fund for Jobs Worth Owning.

You just heard it: the future of home care, or home care cooperatives. That's where it's going. The model works. It aligns the interests of the workers, the clients, the communities. Keeping people on their jobs, keeping them happy, of course, leads to higher quality care. Giving people ownership in their businesses, and ownership lives in that community, of course benefits communities. That's the future. So why aren't there more? You know, there's single digits, double digits, you know, and popping up. Why aren't there more?

Because the obstacle is capital. There isn't that investment capital to grow the space, and we need it, you know? The skyrocketing demand, there is demand for this industry, there is growth to be had in this industry. But who's able to grow? The investor owned home care agencies. That's where the money comes in. Private equity speculation, you know, they grow home care companies, and require double digit returns. And what happens when you play this casino of investment? Workers lose. You know, when those double digit returns have to be paid to grow investor-owned home care companies, those incentivize companies to not treat workers right. Pay lower wages, part time schedules, split schedules, wage theft. I mean, these practices are rampant in the industry. You can see why. Look what the capital is doing. Look what the companies are doing.

Home care co-ops need access to capital. Now, I'm not just talking about the 7(a) loan program. That has issues, we're going to get to that in a second. But beyond loans, which home care co-ops can get, they can get business loans and they get lines of credit. They finance their receivables and things like that. We need equity. We need patient long term investment-like capital to come into the sector. That's what's missing. And the fund for Jobs Worth Owning is a part of catalyzing that, but we need to do a lot more. Got to the next slide.

So the Fund for Jobs Worth Owning is a nonprofit, employee-ownership driven loan fund. We invest in employee owned businesses, start them up, and the quality jobs they create, the jobs worth owning that we create, we we take care of the companies. We make sure they're connected with the right technical assistance, that they're connected with an industry-wide strategy to tap into best practices and ways to have their companies succeed. And we're really driven to be here at the Fund because we want to be investing in industries that employ women, and employ people of color. You heard the majority of workers in health care are women of color. That's where we want to be.

We also do a lot of work at child care, at the Fund for Jobs Worth Owning. Big industries that employ a lot of people, a lot of low income people, that raising the floor and allowing wealth building through cooperatives can make a real difference in their lives. Let's go to the next slide.

So how do we do it? Well, a couple of things. One, there's not enough capital in the space, so there's a lot of need for advising and organizing. The CDFIs and co-op funds do a great job with what they can here, but we still need to put the puzzle together, you know. We need to figure out how to balance the risk, and all that. And so we play a role in helping to bring transactions together. We're also a small loan fund. We do loans for cooperatives; try to do loans that have a higher risk profile, that are more patient. Try to act like equity within the model that we can as a small fund, to design the right products to help cooperatives grow. But a lot more is needed. A lot more is needed in the space. We can go to the next slide.

So in some of the challenges of growing the cooperative space. Well, first thing to recognize is when we're talking about home care companies, we're not talking about asset heavy companies, right? You need lenders. You need investment in these that understands the type of business. These are cash flow companies. They pay back investment with their business model. You need to know metrics. You need to know about the rates, and retention, and client satisfaction, and quality jobs -- the drivers of successful home care agencies -- in order to lend to them. Because you're not liquidating their assets if they go out of business, so you need to be a partner for them. So we need to move out of that asset-based lending when we think about these.

Now, as far as the SBA loan program, it would be great if we could get co-ops to access it. Five and a half percent rate for larger amounts, that's wonderful. We often have to work with institutions that have higher costs of capital, you know, and so paying seven or eight percent, why can't we work with seven, eight? That's the small business program. Why are co-ops excluded? Because personal guarantees don't work with the co-op model. 7(a) requires full and unlimited guarantees on every majority owner. Well, in a co-op, that's everybody. So if you put in a thousand dollars to buy and be an owner of this company, you can't fully guarantee all of the loan. And so that's why the Capital for Cooperatives Act, and other pieces of legislation that can help with the personal guarantee, and get co-ops involved with SBA could be transformational.

And that's also really important for getting cooperatives connected with traditional banks because they have the same personal guarantee issues. You know, we need that SBA program to be a bridge to get co-ops connected with the banking sector that manage things like the PPP program. We all learned it was hard unless you had relationships with traditional banks in order to get the PPP loans, to get them when you needed them. So we need to get co-ops connected with that space, too, and allow the traditional banking space to work for co-ops. So the fund tries to bridge that. We try to bring capital together in the right way, but we need changes in the system as well.

And then, of course, the big pieces investment to grow the cooperative sector, right? We have HUD, who subsidizes nursing homes because we believe those are good. Let's get that government agency subsidizing home care co-ops, because we believe in what they do for the industry, the workers, the clients, the communities that are around them. You know, home care co-ops are made for this moment. This is the moment that we need home care. The future of home care is home care co-ops, so let's figure out the capital so we can make more. Thanks.

Kate LaTour: Thank you, Jonathan, and thank you so much for touching on the SBA 7(a) loan program and the Capital for Cooperative's Act that was introduced today. I'd love to say we timed it, but it actually just happens to be a happy accident that today Senator John Hickenlooper from Colorado introduced legislation that would level the playing field for co-ops at SBA in that 7(a) program. So next, we will turn to Deborah Craig, who will be speaking alongside Nora Edge and Terrell Cannon, so we can hear some personal experiences from home care cooperators. So, Deborah, Nora. And Terrell, if you're able to turn your cameras on, thanks.

Deborah Craig: Hello, I'm Deborah Craig, and I'm from the Northwest Cooperative Development Center, which is located in Olympia, Washington. And you've just heard a great overview of the home care industry, and home care co-ops specifically. And now we're going to hear from some actual home care co-op owners. Is Nora with us as well?

Nora Edge: I am here. I don't have an option to turn on my camera, so I don't really have any of those things.

Deborah Craig: All right. Well, thank you both for being here. And I I know that you would like to talk about the co-op difference. So I'm going to start with Terrell, to just tell us a little bit about the difference the co-op has made in your life. We can't hear you.

Terrell Cannon: I turned the mute on. I said, it's good to be here. Hi, everyone. Thanks for having me here. For me, the co-op difference changed my life. I began this field of work in a traditional nursing home, and I did not have the connection that I thought that I would get in caring for residents, consumers, and things of that nature. I was a young woman on public assistance and I had my children, taking care, struggling and maintaining me and their father to make the ends meet. And I figured, oh, I'll go to the nursing home that, you know, make it {inaudible} for me.

But it did not. It really made me feel real disconnected, and not really wanting to do the work of caregiving. However, it was actually my caseworker at the public assistance office who introduced me to the Home Care Associates Co-op. And I'm like, "wait, the workers own the company?" Like, "I have a chance to be able to have a say?" And, you know, they are telling me I'll share in profits, make major decisions in the company. I'm a part of the growth, the annual growth and success of the organization. My voice is heard. I can sit on the board and I'm like, "naaah, this is a little too good to be true." But I took that step and am still greatly appreciative of the opportunities I got through working in the co-op. And like those before me said, this industry, this work is really -- it's a rewarding job for us to do the work, but like he says, the system doesn't really support the work that we're doing.

So in that co-op, I was able to understand what finances are. I never thought about a bottom line the way that I think about a bottom line today. I never thought, in working in a nursing home, knowing that I would be able to grow within an organization. I sit here now as the director of training, coming from sitting in a chair, being a CNA, looking for a job as a caregiver. So not only am I able to show in my own expertise what a co-op does, but I'm able to help others to join the co-op to understand what it means to be an owner in an organization where you really have the voice, you're appreciated, your work doesn't go undervalued, you get to network and connect with many people like yourself. You know, that makes their relatives want to continue to grow this model. And like you said, this is our time and we really need to grasp at that, and make it much larger. Because if people can really see and know what I feel today, every day when I get up in the morning, working for a co-op -- it's the way of the world. You know, they just have to be able to open their eyes to see what we're doing. And then I said, "I came from the projects, never thought that I'd be sitting on a board."

Deborah Craig: Wow, that's great. What a story. Can we hear a little bit from you, Nora? In your experience in the co-op, how does the co-op support the caregivers to do their best work?

Nora Edge: Oh man, that's a great question, and I just want to apologize, I'm sorry that I don't seem to have a way to turn on my camera. And also, by the way, Terrell, you're a hard person to follow. That was such a beautifully said answer to that question. But, yeah, "how does the co-op support, the caregivers that are...?"

I mean, one thing that the cooperative offers that isn't normative in any {inaudible} services agency, is community for the caregivers. I've worked in management circles where people don't want their caregivers to become friends. You know, they don't want them complaining about their bosses, or their wages, and things like that. Whereas we, as cooperatives, facilitate member engagement at this level where our caregivers not only feel like they have a supervisor, but they feel like they have a support system, in all of the administrators in the office, and in the other caregivers. And I think people are attracted to working at co-ops because they want to build that together. Most of the people who apply at CHC are seeking that community and because of the empowerment of the co-op offers, they're able to create it without any barriers.

Deborah Craig: Great. Terrell, you'd like to add to that?

Terrell Cannon: I do. One of the things as director of training, I just must mention, is that in working with a co-op, the training exceeds the industry standard. And in a lot of organizations, where they do not follow the co-op model, like you said, it's more about what how much money we get in. And basically, they don't -- like, in our training in the co-op, we're not just training on how to make the bed, how to feed someone. We're learning how to read financials, how to run your business, how to network, how to advocate politically. We gain all of this valuable knowledge, you know, that drives us to shape our business and where we work. And it allows us to be able to connect that to others that will take in that information, and join the co-op to make that same difference. But some of the difference that the co-op makes with the workers is also training, because we come out with more expertise than is actually needed for the hands-on pieces of the job.

Deborah Craig: Great. Thank you. Nora, maybe you can speak to how does a democratic workplace benefit the caregivers? Nora?

Nora Edge: Sorry, I was muted. So how does the democratic workplace benefit the caregivers? It's interesting because I think I just want to play yes-and with Terrell, because these questions really relate to each other.

I think membership is the first point of engagement. Our board really makes an effort to reach out to new caregivers. And once their members, they go through a whole onboarding where they offer training and orientation, and make sure that the board members are really connecting with that person, they get invited to join committees. Right now, we have a training committee where any caregiver who joins will get certified to provide state trainings, and can earn an income and professional development that way, or have input into how the trainings are developed and use that experience to help others. So membership, I think, is one of the biggest parts of creating that support and and those opportunities. I think that's the point of access.

Deborah Craig: Great. I know we've talked a lot about the challenges of home care workers. Terrell, do you see any areas where your co-op is really effectively addressing those challenges, that are challenges for all home care workers?

Terrell Cannon: One of the the challenges that was really devastating for home care workers in the beginning of covid was PPEs. Before covid, we've always provided our employees with their PPEs. But what we found is that because we are servicing members in the community that are also low income, we began to offer the PPEs for the aides, the workers, to present to their consumers. And we've given them the education on how to use it, be safe, maintain safety in a home, you know, having to distance from relatives in the home. We've also put more initiative in our rewards and recognition, and recognizing that our workers are out there during is trying time. And with the stress and anxiety and all of those things that come with it, and fear of being affected or affecting their loved ones or people in their community, they still were resilient and committed to the service workers for our consumers. So we put a lot of effort in our programs, our employee programs, to continue to support our workers to continue to do a great job, as well as do a lot more community advocacy work to make others in the community that we serve aware of the challenges of covid, to kind of even out the playing field a little bit, to relieve some of the stress and anxiety of our employees.

Deborah Craig: You know, one of the things that was brought up in the previous presentation was the turnover rate, and that's one place where we really shine in the home care co-ops: our turnover rate being lower. And we know how that affects care. Could you both just briefly speak to what does your co-op do to retain these workers? How are you retaining workers that other people can't? Nora?

Nora Edge: Sure. Man, I'm thinking about it, especially in the context of covid-19. You know, recruitment and retaining people is still a huge problem. But I think, kind of similar to what Terrell is saying, you could really put CHC's covid experience in a vacuum as why we can retain people. You know, we saw other home care agencies, or caregiving agencies, really threatening their workers. "If you don't come in, because of symptoms you'll lose your job," or things like that. And what I see with CHC is, you know, I think the sense of ownership and that can mean a lot of different things for a lot of different people. If people start connecting with that, that keeps them there. And I think that sense of investment, along with, as you and Katrina pointed out, the relationships you build, it makes it a hard job to leave if those things are happening well.

I would definitely say, for instance, that CHC, instead of having all of our caregivers exodus -- which I think happened in a lot of different places -- or having people who are resentful and scared; we had people who offered to, or suggested, that I lower caregiver wages to make sure the business survived, or offered their sick time or PTO hours to people who were quarantining, to help them stay above water. And I think just those little gestures speak so loudly about what that co-op difference is, because I just don't think that that would happen in any other circumstance. And all of those people -- and we lost a ton of business -- they stuck it out when they had like two hours a week for a month. It was a big deal that those caregivers stayed. And we retained our whole base. You know, we certainly had people who applied and didn't really stick around to find out what it's like. You know, leaving in a month. Maybe that's just something that happens no matter what you try to do. But I mean, we do see that once people start tasting that culture, and feeling how special it is, they don't want to let it go. They're looking for that.

Deborah Craig: Great. Terrell, anything your co-op does specifically that you think really helps with retention?

Terrell Cannon: We put a lot of things in place when covid hit earlier in the year -- I mean, last year -- our employees were working, the kids were home. So we started out with instead of them coming to the office to get their PPEs and things, those of us as staff, began to take it to them, to their consumer's homes. To make it easier for them to just be able to minimize the time that they would need to be away from home, or had the babysitter in the home. In the later part of the end of the year, we allowed our employees to cash-in their PTO time if they chose to, so that it could allow them to have some more income in their pocket. So while we were very supportive on the times when people may have called out because of fear, or things like that, we didn't just push policy, we worked a lot with our employees. We also taught some of our other employees how to access the internet, and do virtual zooming and things.

And I know those things might be small and minute to some, but they were very huge to our workers that were not savvy of how to use telecommunications. They didn't really grasp it, so us and staff took the time to go to them, to sit with them, teach them those things. We put a lot of systems in place within the organization to make it a lot easier for our employees when they have to maintain compliance and things like that, while still having to juggle with the kids, and being at home schooled, and running back and forth, you know, store runs for their own parents, and still providing quality service for our consumers. So for us, it was just to alleviate some of the stress that they will go to day-to-day, that we put in place so that our workers -- and like you said, they stay, and they're worker-owners, and they feel committed to the success of the organization. So we know that they're going to go 110%. But at least let us take the 10 percent to help you keep up to the 110.

Deborah Craig: OK, thank you both very much. I mean not just for today, but for the work that you are doing day-in and day-out. I think we are going to ask you to stay on for some questions. And we will...if we have someone coming on...yes, OK.

Kate LaTour: Yes, thank you Deborah, and thank you Terrell and Nora. I could listen to first hand experiences all day. I think it is really -- we can talk about the data points and those certainly help make the case, but it never becomes clearer than when you hear it from from firsthand providers.

So with that, I would ask our other presenters to turn on their cameras. And we have several questions that have come in. I'm going to try to pull them together. And several of them are kind of {inaudible}. I can see lots of folks might have something to add, but I will start with perhaps from Terrell and Nora to start, and then I suspect others might want to supplement. But how do small home care co-ops compete with national chains? There's a lot of questions that came in around some of the consolidation or really the giant players in the field. So Terrell and Nora, are there marketing components, or how do you as co-ops compete with those bigger firms?

Terrell Cannon: One of the main competitions is the pay rate with the larger firms, because their pay rate, of course, is much higher. But in the co-op we offer more to the worker so that they can maintain the pay rate. And one of the things we do is educate the workers on what the benefits are, the pay raise or how you use it and go through what it's like when, you know, let's say I'm getting twenty dollars an hour at this place, but I'm not getting benefits of paying for my transportation. So we help them to break that down to see what the real dollar amount is. So then when they join the co-op, they see that they're getting -- yeah, you might see this 12, 13, 14 dollars an hour, you know, documented on your stuff, but you see that 25, 30, 40 dollars an hour and the worker ownership. You gain the knowledge and training that you get, you see it in the support that you get in the workforce, the decisions that you make in the workforce, and your voice, and your work being valued.

So, the challenge is always that you have some people who are at the point now where they just need to work for money for those bigger organizations, than it is for those that say, you know, "I want something sustainable, I want something I can grow with, I want something I can build." And that's sometimes the struggle a little bit, is really getting people to understand and buy into the co-op model, believe in it when they haven't actually felt or touched it. So that, for me, is the big challenge, along with the reimbursement rates as well. Because, again, if the government is going to see it as a valuable asset, then why would the buyer. So that's one of the hardest challenges in getting this co-op model driven across the nation so that -- and it would be a better world because everyone would be invested and providing quality care, and providing a successful business, and growing the network. But for me as a worker owner, it's usually those entities -- and when I'm out recruiting and I see them out there -- and they call me a bit of a tyrant, but it's OK because I need you to understand why I'm still here 30 years later, you know, and they just started, you know, 10, 20 minutes ago. We've been here and we have mothers along where -- and I often not just talk about the home care co-ops, but we have food networks that are co-op. We have so many co-ops in different facets that benefits us all, because we connect with each other. So it's really the challenge of getting people to see the model as, "this is it. That shouldn't exist. This is what should exist."

Kate LaTour: Terrell, thank you. Reading the questions that have all come in, I think you hit on several points that folks were interested in hearing. We'll, digging a little deeper in a second. Nora, did you have anything to add there on kind of the a little bit more on the co-op difference competing, with bigger chains and those bigger companies?

Nora Edge: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, definitely everything that Terrell said. You know, the biggest thing is the wages, the reimbursement. For instance, we are still private Capital Home Care, so we've been able to outpace our competitors in wages. We pay about a dollar more than our highest paying competitor, which is really good. But that wouldn't be possible if we were taking public pay. So I would say those basic things, like trying to make it an attractive job.

The only other thing I would add -- and this comes from some of these start-ups of the past two years -- is like there's no way to compete with the budget that these multinationals owned franchises have for marketing. You know, there's just no way you're going to be as visible and branded as they are, unless something really changes for all of us. And so my strategy -- and I think that this has actually proven really successful -- is knowing that having a good local word of mouth for your clients and your caregivers is about as valuable as like $20,000 a year in marketing. So that's been where I've been really focused for the past three years, creating a strong reputation of quality care to the point where other businesses reach out to us because they've heard such good things, and that's how our partnerships start, which is way cheaper. Just putting that out there. So, I would just say that to try to compete with what they're doing is almost -- I would say it's very difficult, but starting out just really thinking about who you are, how you appeal to caregivers and help them to advertise for you.

Kate LaTour: That's a really good way to phrase that. I think that's an excellent context. I want to open up to anybody else on the panel here to add to that.

Katrina Kazda: I'd love to jump in if I can. This is very close to heart for me. It's such a big problem, it's such a big challenge. It's sort of an uphill battle we're constantly fighting. I think there's two things I would say. One is that we do need to actually scale the size of home care cooperatives. There's absolutely a space for small cooperatives that are really community based. And it's not that we want to replace that, but we also need large scale cooperatives and to be moving in that direction so we can compete one-on-one with some of the larger entities. But also, this is a really big focus of ICA's work, and also Deborah Craig at Northwest Cooperative Development Center, to really push for greater cooperation among home care cooperatives, and really looking at building the state level and national level associations, and really networks where we can work together to, for example, market home care cooperatives at a national level. So that's actually a project that we are actively working on right now, where a number of the cooperatives, including some on this call, are going to be coming together. We're going to be building a national digital marketing and sales platform. And so there's huge power in working together as home care cooperatives, both at that national and state level, and then also that cooperation among cooperatives in other sectors. There's a ton of opportunity if we really think big picture. So I think we can, it's going to be hard to Nora's point, but we can compete, I think, once we come together and really pool our resources. We're much stronger that way.

Kate LaTour: Truly, again, you guys, may as well be reading the questions I'm seeing. And, you know, NCBA CLUSA loves some Principle Six: cooperation among cooperatives. So I think those are all really great points. I do want to just leave open space for anybody who wants to add to that, because I think this is a really important point. OK, then I think I wonder...well, actually, I'm not sure who would be best to answer this, so I'll -- you know, it's been touched on a little bit, the difference in pay that co-ops provide their providers, and both -- what is one of the driving factors? And I think Nora started to talk about it, comparing to Terrell's Co-op, but why is the pay so low in this sector? And what are some of those ways that co-ops are working through that?

Kezia Scales: I could start with just the overview, being the sort of structural drivers of lower wages in the sector, being that the largest payer of long term care overall is Medicaid and the overwhelmingly largest payer of home based care is Medicaid. So we're looking at up to 80% covered by Medicaid. And as we know, Medicaid sort of has become by default the largest payer, but was not designed to support our long term services and support system in a sustainable way. It is a means-tested payer-of-last-resort, really. And it's a state-federal partnership with a lot of ownership at the state level. And it's always subject to political challenges. So every every budget season it's subject to being changed and adapted, and funds may be compressed. All of that is to say that Medicaid reimbursement rates are what drive what providers can pay for the most part, except for those who entirely accept private pay. And the margins on those reimbursement rates are so slim that providers for the most part are paying the highest wages that they can within the reimbursement rates. So one of the major structural changes I think that we really need is a really rigorous reckoning with how much does it really cost to provide high quality home care, and what costs go into that full cost, and how does that need to be reflected in the Medicaid reimbursement rates? And in the context of managed long term care, which is sort of an intermediary payer in a lot of states? What is it that managed long term care companies or organizations need to be responsible for, or accountable for, in terms of how much they pay to their contracted provider agencies?

Kate LaTour: And in that same vein, is there opportunity -- you know, Medicaid is this enormous player -- is there opportunity, for example, with state and local agencies or with the VA? Where is in this in this competition?

Katrina Kazda: I could comment, just so I know, VA actually, interestingly, has recently made a very large investment in home care and home based services, and has increased their rates pretty dramatically, making it very possible for agencies to provide high quality care. And so that is a place where home care cooperatives, many home care cooperatives, are looking to expand services, based on sort of the conditions that Kezia is talking about. You know, a lot of the home care cooperatives that have been focused on Medicaid primarily, and on public pay services, are now really needing to look into expanding into the private sector, expanding into VA, and looking at other payers, just given that it's truly not sustainable unless you are really at these very scaled sizes to be able to do that sustainably. And that's a real shame. Then we're moving the quality away from many of the individuals who most need it and cannot afford to pay for it on their own.

This is maybe going back a little bit to the original question. But I did want to say also that in home care, similar to child care, what individuals are able to pay on the private market, there's a limit to that as well. We need public investment. You can't constantly push that level up. That means that then a very, very small percentage of the population can actually access and pay for high quality care. So the whole structure is not working in that way. We need to have that public investment.

Kate LaTour: Deborah, did you want to add anything there?

Deborah Craig: No.

Kate LaTour: Well, then I'll turn to Jonathan next. The question is pretty straightforward. When other lenders are nervous about removing the personal guarantee, what do you say to those -- oops, sorry -- what do you say to folks using more of a collective guarantee or some other alternative?

Jonathan Ward: Yeah, that's a great point. Know, the personal guarantee is the bane of cooperatives. Been saying it for years and years now. So, really companies just need options. You know, the full and unlimited guarantee thing is just way too heavy handed. It's from an era of capitalism and doesn't make sense for home care agencies. But collective guarantees, when we say, you know, "how much is the debt that we're taking on? Can we share it in some way in the system instead of have all of our selves tied up and all of our personal assets?" So, yeah, the collective guarantee is an option. I think in a lot of ways we need to be able to look beyond guarantees too. What other factors keep people at their jobs when things gets tough? You know, quality jobs, tenure, fair wages, you know, being treated with dignity and the culture around that. It's not just the fear of losing your car and your house -- you know, a lot of workers don't have cars and houses like that either. So the whole system of kind of guaranteeing your assets to keep you there so you don't run away, it doesn't make sense for home care. And so I think we just need a suite of options that makes sense with the reality of the business. But businesses that have a strong management team, a good business strategy, long tenured workers, worker-centered policies and practices, a democratic board of directors, I think we need to look at those things, to look at the sustainability of a company and not just how big your house is, and can we liquidated if needed.

Kate LaTour: Yeah, this is one of my soapbox issues, so I appreciate you answering that so eloquently. We are about -- we have four minutes left in our conversation today. So I do want to kind of open it up. I know this conversation deserves hours and hours, even though we're well into seventy five minutes. So I guess I'll open it up if folks had burning last comments, or what they really want to make sure people walk away with.

Terrell Cannon: I would say I want people to walk away with knowing that there is an opportunity, there is a chance, there is a movement in the co-op model, and to just embrace it. Embrace it and participate, engage yourself in the workings of the co-op model to understand and to gain the knowledge to know how to better succeed in the co-op model.

Kate LaTour: Thank you. That's great.

Kezia Scales: And I would add, again, just that this is the moment that home care is getting more attention than maybe it ever has before, and we need to seize that moment. And as we're talking about the need for quality jobs in the sector, we must look to home care cooperatives as the model. And we can learn from home care cooperatives about that model in particular, but also even more broadly about what it looks like to center workers in your business, and in everything you do, and how that connects to better quality jobs and better quality care outcomes. So the ripple effects are potentially really transformational for the sector.

Kate LaTour: Thank you.

Katrina Kazda: OK, if I can step in, there's so many things I want to say, but maybe the one thing I really want to convey is that caregivers are not the problem in the caregiver crisis that we're facing right now. Caregivers are incredibly hardworking, dedicated people who love caring for people. And there's a real misunderstanding around that, and also a real lack of recognition of the skill and intelligence of home care workers. Given the soapbox, I need to say that here. The problem is the lack of investment and the lack of respect that is assigned to caregiving in general, and definitely caregiving and home care, both in the health care space and society as a whole. So if we can shift that thinking, which is not a small task, we'll be on the right path because the people that are doing this work are incredibly intelligent, incredibly capable, incredibly hardworking. So we have that base to build on. But the investment needs to be made there to elevate caregivers to the position where they belong.

Kate LaTour: That is such an important point.

Nora Edge: Well, said Katrina.

Jonathan Ward: I can just end by saying maybe a reminder that we want growth. I hope this model has proven itself here in so many ways: how it feels, the results of it. We want growth. And what does growth take? Investment. Home care co-ops need access to capital, so they can invest and grow and but the returns need to be reasonable on it.

Kate LaTour: Yeah, and I think I would I'm going to take the liberty as moderator to take it one step further, that they also need access to technical assistance. What any small business can go to a small business development center for, co-ops don't have that same access. So at NCBA CLUSA, we focus quite a bit on the Rural Co-op Development Grant program, which does wonders, but is vastly insufficient. And there is no non-rural companion program. So I think that technical assistance component, which both Katrina and Deborah Craig, you guys are providers {inaudible}. So I think it's really worthwhile noting. Did we miss anybody on final comments?

Nora Edge: I just wanted to say thanks for putting this on you guys, it's been fun.

Add new comment