How can technology build a co-op economy?

This is the question that motivated Co-op DiscoTechs. And because it was May Day, we started by talking about co-ops and the labor movement.

(Here are the slides that accompanied our conversation)

In the co-op world, many enthusiasts buy only from co-ops, as a rule. Are co-ops already better than all alternatives?

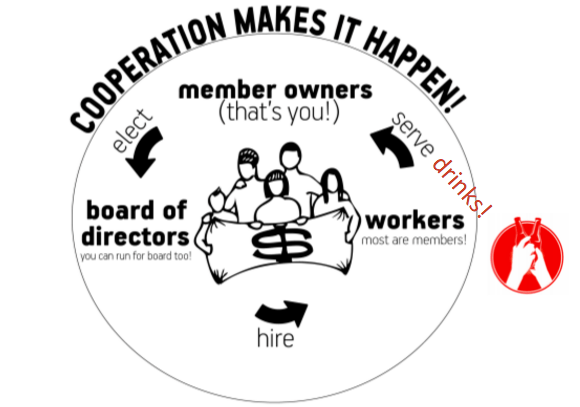

Sometimes. One great example is the Riverwest Public House, a co-op bar in a neighborhood of 100 bars that grows by “building community, one drink at a time.” More drinks and events means more people who get signed-up as member owners, elected as board members, and hired as workers. Their model is a virtuous cycle that makes many friends.

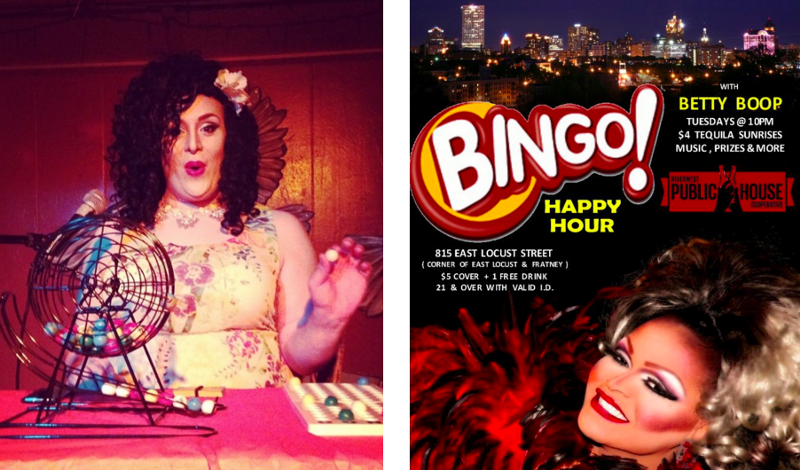

I talked to the Public House membership coordinator, who told me that they’ve become so welcoming, inclusive, and democratic, their bathrooms doors read “stand” and “stand/sit” and their community fills their event calendar — drag queen bingo (Tuesdays at 10pm!) is the most popular by far.

Meanwhile, other well-known co-ops have a history of exploiting people. This is much worse than bad meetings.

Sun Maid Raisins, founded in 1912 to support stable demand and fair prices, is a producer co-op owned by over 800 family farms. And yet, because of their abusive working conditions for grape pickers in the 1960s, the United Farmworkers targeted them with a 5-year boycott.

Are they that much better today? Is it enough to say, #notallcoops? No.

Technology isn’t necessary for bars or farms to become better co-ops, but it can help.

Two coalitions that embrace co-design — civic tech and online organizing — can offer lessons on how to build better tech.

At the same time, co-op theory and history offer a model of how to own, control, and share the value generated by the tech we build.

While each area has its emphasis, each can learn from the other, too:

-

Civic tech is a coalition for better citizenship, trying to achieve citizen engagement. An example is southbendvoices.com, an automated call-in system. Yet tweeting the city to shut off sprinklers after the rain is a far cry from building better neighborhoods. What could it add? Economic solidarity.

-

Online organizing is a digital approach to social change, trying to achieve community power. An example is 18millionrising.org, a group running rapid-response campaigns for racial justice. What’s missing? Platforms that support lasting effort with multiple allies.

-

The co-op movement is about democracy in the workplace, trying to achieve real ownership, control, and value for the people doing the labor. An example is the Arizmendi Association, an umbrella group supporting six worker-owned bakeries. It’s a model that only the Enspiral network has replicated in New Zealand. What potential remains untapped here? Widespread relevance.

How might all three of these areas become better, together?

That’s what we were going to find out — first, by building shared understanding and reaching (useful) disagreement.

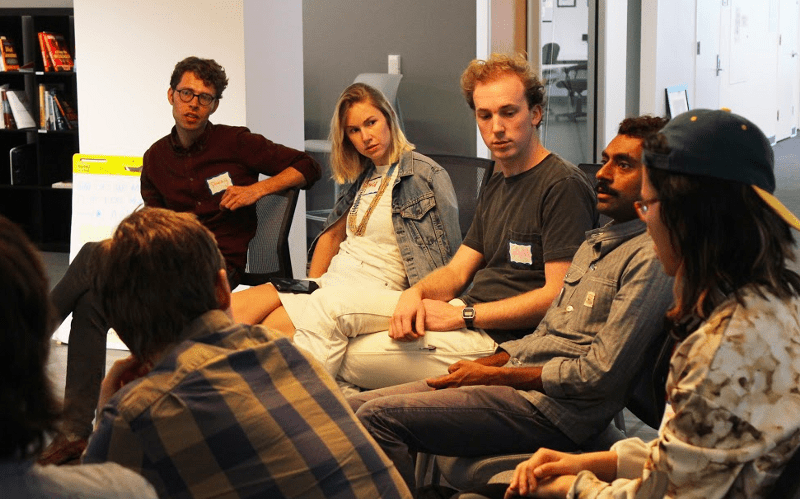

Vikram Babu (2nd from right) shares his nuanced views on tech labor / photo by Molly McLeod

There are co-ops, and then there is cooperation. Shane from CCA asked “what counts as a co-op?” and Willow Brugh from Aspiration Tech described a multi-stakeholder project in Africa that supports self-determining small businesses. I mentioned how Enspiral exemplifies the first co-op principle of open and voluntary membership better than most legally-recognized co-ops with a quarterly auto-email to their 30 member organizations that simply asks, “Do you still feel like a member?”

There are parallel worlds we can learn from, if we take care not to reproduce extractive practices. Developer and counselor Kermit Goodwin suggested that the open source community might be a place to learn more, and Noah Thorp of CoMakery cautioned that while developers might play better, the open source software economy is “broken” and dominated by corporate interests — most of the people making a livelihood through open source software do so through extractive enterprises (think, Microsoft).

And then there is the agitation and education that leads to organizing. After Evangeline asked “Why do people stop trying?” and how we can make co-ops familiar to more people, Molly McLeod brought up relatively passive directories like cultivate.coop and showed us Co-opoly, a boardgame about starting worker-owned businesses and having all of the poignant conversations that go along with it. Jackie Mahendra from CEL said her first serious role was working with a co-op house, and then others agreed co-ops can stay relevant if they provide services more widely — housing, education, health care, consumer finance, and more. Building viable co-op platforms is exactly what the creators of Platform Cooperativism are organizing around.

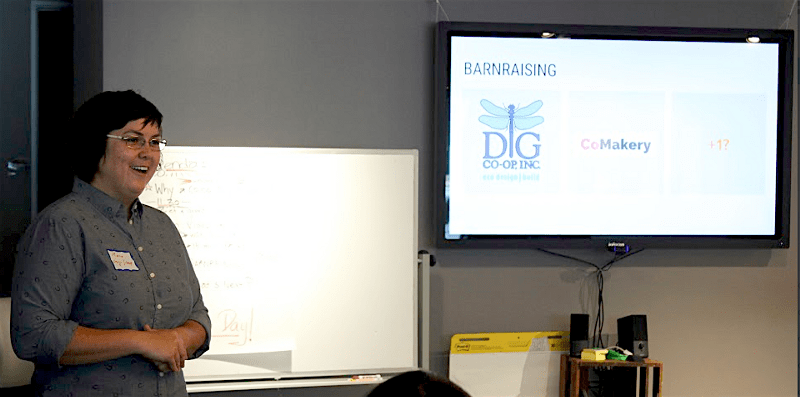

After finding some common group, we turned our attention to two projects: DIG.coop, a local landscaping firm looking to merge with two other groups while maintaining their co-op values, and CoMakery, an equity-sharing platform for cooperative entrepreneurship.

Barn-raising

0. The presenter for each project said a few words about their work. Everyone gathered around the one they’re curious about. Then,

-

Presenter describes their work and its main challenge (10min)

-

Participants ask clarifying questions (no comments/ideas)(15min)

-

Everyone shares ideas, proposals, etc. for making progress (25min)

-

Facilitator synthesizes a synopsis to share back with everyone (10min)

Total=60min. Several people asked for 90min or more next time.

Danny Spitzberg

DIG.coop, the landscaping firm, re-discovered the beauty and utility of “water conservation,” their founding mission, as a metaphor to uphold their cultural values — especially in their upcoming merger with two other groups.

CoMakery, the equity sharing platform, explored questions of how to not involve lawyers, how to favor working with people that look different, and how to compensate all kinds of inputs. After doing user journey mapping, they planned to test a currency for new projects.

But wait, there’s more!

Finally, everyone shared ideas for the next event. Here are a few:

-

More time to participate in barnraising around more specific challenges

-

Special guest speakers and small group talks (“office hours”)

-

Education on select topics (how might co-ops do rapid decision-making?)

-

Creating shared language around co-op entities (what is a co-op, really?)

Paige from Tech Workers Coalition, a group organizing around labor, said that “it feels like we’re at the outset of something really meaningful.”

Help make the next event happen! We welcome members of co-op projects, event organizers, and participants — ?? Sign up here!

Special thanks

A thousand thanks to The Citizen Engagement Lab for hosting, and to Arizmendi Bakery, Mandela Foods Co-op, and Bicycle Coffee Co for providing our May Day brunch.