This article was originally published in the NCBA Journal’s Summer 2017 issue.

by Danny Spitzberg

The fight for a free and open Internet scored a win in 2006, thanks to a bad analogy. Alaska Senator Ted Stevens argued that Internet service providers should have the right to manage traffic from sources that “flood the Internet,” which he likened to “a series of tubes.” Companies like Comcast could filter competitor ads or political content. Worse, they could charge extra for watching Netflix. To prevent this discrimination, users joined the Net Neutrality movement to protect equal, unfettered access to all websites, applications, and data.

As silly as Stevens’ ideas may sound for the Internet, congestion was a serious cost for newspapers in the early 1800s. News cables could only carry one message at a time. Publishers found themselves in a bidding war to get reports, until in May 22, 1846, when five of them formed the Associated Press, a joint venture that split costs and shared news.

Much like Internet today and cables before, AP had become a utility. And for decades, it grew to serve its exclusive membership and charge competitors whatever it pleased, until a 1945 Supreme Court ruling intervened. AP converted into a nonprofit media cooperative, opening its membership and adding accountability to the general public.

Today, online news is a very different beast. Net Neutrality legislation barely passed and it is under attack again. The Associated Press has become a lonely source of trustworthy reporting. And Twitter, a website and app where users post 140-character tweets, has become a vital news utility. Twitter, Inc., is a publicly traded company in Silicon Valley valued at around $12 billion. It has a large proportion of retail shareholders — around 60%. However, most decisions are left to its executives, board, and a few large institutional shareholders.

We depend on just a handful of digital platforms for everything from business operations work to our personal life, but have no meaningful control. Inclusive company ownership is key to democracy. If Silicon Valley can disrupt whole industries, why not innovate with company ownership, too? For almost a year, Twitter has been on the edge of acquisition by a major company. Why not consider a conversion to a cooperative, instead?

If Silicon Valley can disrupt whole industries, why not innovate with company ownership, too?

The cooperative movement has enough history and insight to play a leading role in the economy, especially with well-known and much-loved models like AP and REI. However, we’ve been slow to build the strategic capacity required to convert large enterprises, and especially digital platforms. By organizing a campaign for Twitter to become a cooperative, we can leapfrog to more inclusive ownership of our economy.

On May 22, 2017, the same day that AP marked its 171st anniversary, I joined a few dozen Twitter shareholders gathered for the annual general meeting at the company’s San Francisco headquarters. Founder and CEO Jack Dorsey shared his belief that Twitter can be “the first place that people go to when they want to find out what’s happening.” In other words: a news utility. Myself and thousands of other users and shareholders knew this, of course. Our interest was to hear the voting results on our proposal, to study conversion of the company into a cooperative.

Nine months earlier, Twitter found itself in the news for different reasons. Its stock price fell to around $14 from a high of $66, and reports came out about Twitter seeking to sell out in an acquisition. Most articles highlighted the gap between Twitter’s valuation on the stock market and its value to society. As a news utility, Twitter plays an outsized role. Its 300 million monthly active users in the first quarter 2017 were far fewer than Facebook (1.9 billion), YouTube (1.0 billion), and even Instagram (700 million) but every day, television news anchors read tweets, like newspapers reference AP stories.

The more we depend on Twitter to get our news or make our voices heard, the more we care about who owns and controls it.

Twitter is unique in how it helps make the news — and shape history, too. The platform’s public posting default and hashtag features make it easy for social movements to amplify their message. In 2015, 14 activists shut down the San Francisco Bay Area subway system by chaining their arms through a subway car stopped at a station in West Oakland. They planned the demonstration for four-and-a-half hours, drawing national attention to the time police in Ferguson, Missouri waited before giving medical attention to Michael Brown, an unarmed black youth shot by an officer. And within minutes, the transit shutdown caused a social media uproar. Commuters took to Twitter to share views about the delay, many of them using the hashtag that activists printed on their shirts, and that tens of thousands of tweets echoed that day: #BlackLivesMatter.

The more we depend on Twitter to get our news or make our voices heard, the more we care about who owns and controls it. Champions of a free press doubt Twitter’s ability to play a role as an unbiased news utility. Media analysts believe Twitter tolerates ongoing harassment and bullying to boost use, views, and ad revenue. And users understand they have no say in the company downplaying trending topics, refusing to promote specific content, or shutting down controversial accounts.

To say users on Twitter are loud or have strong opinions is a bit of an understatement. But with one-share, one-vote as the norm, users and small shareholders have virtually no voice or influence in how Twitter is governed or operates. With chaotic stock prices and politics threatening Twitter’s survival, there couldn’t be a better time to explore innovative alternatives to an unimaginative acquisition for short-term gain.

Realizing Twitter’s immense value to news and social movements, a group of cooperative advocates and researchers decided to start a thought experiment. How might we protect and strengthen the platform in ways a for-profit, publicly traded company can’t? What would it take for users to buy Twitter and form a cooperative?

In November 2015, several hundred technologists and a few dozen leading lights in the free software and open source movement came together in New York around a multisyllabic shared interest: platform cooperativism. The conference culminated in an edited volume, “Ours to Hack and to Own” a year later, and slowed to a trickle of conversation, mainly via email and on Twitter with the hashtag #platformcoop.

Shortly after reports came out about Twitter, Inc. exploring an acquisition, one of the co-organizers, writer and cooperative scholar Nathan Schneider, sent an email to the group asking, What can our movement do? I’d been helping build cooperative platforms for several years, shared my analysis and analogies. Yes, a multi-billion dollar company could become a co-op. Look at how the Associated Press was transformed or how Green Bay Packers football fans kept their team in Wisconsin through a nonprofit!

Nathan put the idea in writing, and The Guardian ran it as an op-ed on September 29, 2016 with the headline, “Here’s my plan to save Twitter: let’s buy it.”

The op-ed spread across Twitter almost immediately. Hundreds of users tweeted it, some adding #WeAreTwitter and #BuyTwitter. To keep building critical mass, our group started a Twitter account, @BuyThisPlatform. We clicked ‘Like’ and ‘Retweet’ and replied. Using Loomio, a decision-making platform, we also created space for discussion with allies.

The idea resonated across the spectrum of stakeholders. Based on tweets, articles, and conversations in our growing organizing group, my understanding is that people saw a cooperative alternative as equally provocative and sensible. Rachael Lamkin, an intellectual property lawyer, said she saw democratizing Twitter as a stepping stone to overhauling Uber. An article in the November 2016 issue of WIRED, a magazine about technology and politics, was predictably positive: “It makes perfect sense.”

our group moved the conversation beyond the choice of public or private, by pointing to another form of ownership: the people

Another explanation for the popularity of a co-op buy-out is simply it’s newness to a mainstream audience. The U.S. business community has a limited imagination about ownership — even more so in Silicon Valley, where companies aspire to either go public or get acquired. As Twitter’s fate hung in the balance, speculation stuck to one line of thought: What would Twitter become as part of Salesforce, one company to publicly comment about buying it? What about Google or Amazon? In contrast to that guessing game, our group moved the conversation beyond the choice of public or private, by pointing to another form of ownership: the people who use Twitter.

We began by talking about how shared ownership and community control could save Twitter from Wall Street. We argued the company should share its future with those whose participation makes it so valuable: its users. We also knew that any chance of success depended on organizing shareholders. No small shareholder fools themselves into thinking they have any real power — certainly not on their own, and not even in aggregate — without getting organized.

In the 60’s and 70’s, labor activists Dolores Huerta. Philip Vera Cruz, and Cesar Chavez united thousands of California farmworkers and their families to a march, and later boycott, major agricultural companies — including at least one grower cooperative. They demanded basic rights and fair wages. And against all odds, they won.

The farmworker organizing involved many people patiently building relationships across cultures, which activist and now lecturer Marshall Ganz participated in for 16 years. Writing about the social movement that grew in California, Ganz concludes that in David-versus-Goliath fights, the reason David sometimes wins has less to do with charisma or the good graces of a higher power, and more to do with what he calls “strategic capacity.” Effective leadership means creating and utilizing resources, from action plans to political power, as opportunities arise.

The case for Twitter becoming a co-op revolved around the fact that our news utility was under threat, but for average users, their use of social media and their financial investments were separate matters. Our week of frenzied tweeting had turned into a month of organizing with nearly 200 individuals. Our more financially minded allies urged us to ground the idea in reality. Rachael Lamkin, the lawyer, did back-of-the-envelope math about how many of Twitter’s 300 million users we would need to crowdfund $7 billion, a majority share of the company. Many critics did the same math. There had to be other ways to influence Twitter.

Maira Sutton, a former digital rights policy analyst, suggested we create our first piece of strategic capacity: a two-page plan. We’d drafted a petition, but didn’t know what it should do. We came up a goal to make the case for Twitter to become a user-owned co-op, or else persuade Twitter to develop its own alternative to Wall Street. We would do this by uniting users and shareholders who believe Twitter has yet to realize its full potential — and value — as a news platform. The document outlined ways to apply pressure on Twitter, Inc. and escalate over time.

For many of the organizers in our collective, this campaign was their first experience facing a company as large as Twitter, Inc. We had the challenge of setting expectations while sustaining excitement.

For many of the organizers in our collective, this campaign was their first experience facing a company as large as Twitter, Inc. We had the challenge of setting expectations while sustaining excitement. Trying to decide on a minimum number of signatures for our petition helped us clarify that we needed to focus at least as much on political power as financial capital. Did we need 10,000? 100,000? Even 10 million is less than 1% of user accounts on Twitter. More than score signatures, we aimed to earn coverage in major press outlets.

Within a month of posting our petition, we collected 3,000 signatures urging Twitter not to “sell its users to Wall Street.” Sign-ups slowed to a trickle. But we caught media attention across the board, from the Financial Times to Vanity Fair.

Unsurprisingly, as December rolled around, nobody from Twitter responded. The initial excitement had subsided. Nathan’s op-ed remained the high note of our campaign. Half of our early organizers returned to other work or faded away, including one former stock market trader who seemed a bit too excited to help set up a checking account where we could deposit the $7 billion people would crowdfund for co-op shares.

In organizing, a petition is barely the beginning of a conversation. Organizers typically find who they want to influence and deliver the stack of signatures in-person, raising a ruckus. We didn’t have any plans, or motivation, to do that. Instead, in early December, we created more strategic capacity by evolving our petition into a proposal.

Proposals are the building block of any cooperative. Ours sprang out of a conversation with housing activist Sonja Trauss, who knew little about coops but had petitioned Twitter a year ago. She thought #BuyTwitter made limited sense. More users owning shares means more voters, but Twitter is already publicly traded. Any shareholder could speak their mind to the CEO at the annual general meeting. Why make Twitter a co-op, Sonja asked, when it’s pretty much there?

I hope you, dear reader, take pause with this question. Easy answers like “democratic power” or “one member, one vote” are not enough. Even as bumper stickers, they leave something to be desired. And co-op slogans like “we own it” do little for Sonja or people outside the movement.

On Loomio, I relayed my conversation with Sonja to the organizing group, proposing we start organizing with shareholders in earnest. One of organizers immediately recruited a friend and publisher of CorpGov.Net, Jim McRitchie. Jim has spent two decades submitting shareholder resolutions that improve company performance. Jim has a handlebar mustache not unlike a Wild West sheriff. He is also a Twitter shareholder.

By early December, #BuyTwitter had amassed several thousand signatures, email subscribers, and followers. It seemed like we might have what it takes. Jim, Sonja, credit union expert Matt Cropp, and a dozen others joined in-person and online to collaboratively write a first draft of our proposal. Finally, we had something tangible to hand Twitter. To participate in the process and vote, a few of us bought shares in Twitter, too.

As predicted, Twitter’s legal team tried to block our proposal. They filed a no-action request to the Securities and Exchange Commission with the argument that studying democratic user ownership was micromanagement, and a distraction, essentially claiming Twitter’s stock would soon bounce back.

At this point, our organizing group had amassed many reasons and scenarios explaining why a cooperative conversion would save Twitter and increase its value, too. Using that, Jim drafted an appeal to the SEC stating that studying new ownership models was the opposite of business-as-usual, and in no way interfered with day-to-day operation. In a year when many companies have rolled back shareholder rights, democratic governance deserves critical attention.

To our amazement, the SEC ruled in our favor. They directed Twitter to put our proposal to a vote by shareholders. Twitter released its annual proxy statement, a document providing shareholders with information to vote on proposals. The proxy included the text of our proposal and Twitter’s written opposition that urged shareholders to vote against it.

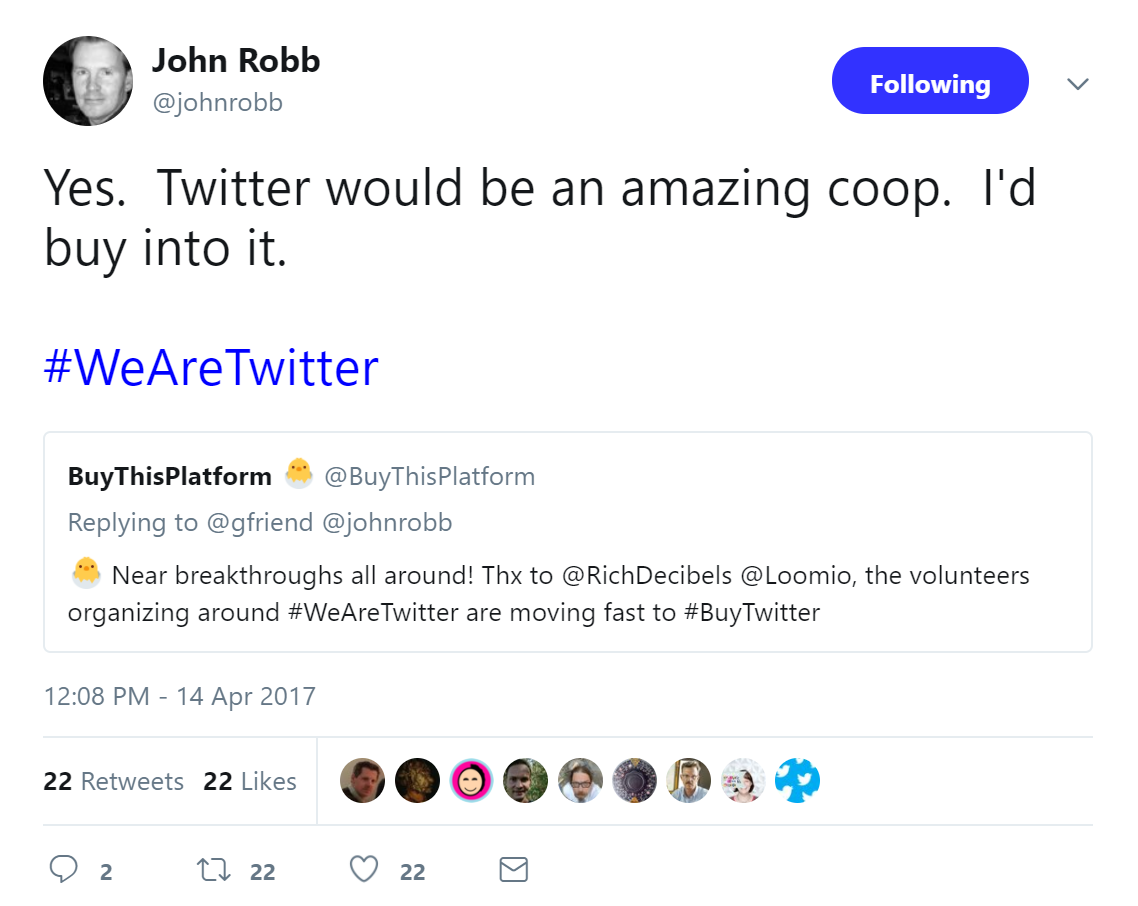

As a high-profile company with its stock in flux, Twitter’s proxy document was highly anticipated by journalists. #BuyTwitter received another wave of press with a mix of interest and amusement. One headline read, “Of course, a bunch of Twitter users want to buy the company and turn it into a co-op.” Even more amazing, dozens of users and shareholders tweeted with enthusiasm and rational self-interest. @johnrobb’s tweet represents the best balance:

Now, after nearly nine months of patient, volunteer organizing, #BuyTwitter could finally live up to its reputation as a movement.

Voting on our proposal opened in early April, and would close at the annual general meeting on May 22nd, for those attending in-person.

To get out the vote, our three working groups for campaign strategy, business analysis, and digital organizing went into action. We launched buytwitter.org to continue signing up shareholders, wrote a three-step voting guide, posted a full list of our press coverage, and featured tweets from shareholders committed to voting Yes.

Winning votes, however, required that we more fully explain why a cooperative model might deliver returns to shareholders of a tech company. Albert Wenger of Union Square Ventures, one of Twitter’s early major investors, wrote a blog post supporting #BuyTwitter. He recognized that Twitter’s value depends on maintaining a dominant network, adding that “this also has the potential for setting up a deep conflict between companies that operate networks and the participants in those networks: the value to shareholders can be increased through rent extraction from the network. And with many network effects companies reaching near monopoly status the potential for harmful rent extraction has grown.” Clearly, he wrote, experimentation with ownership models is essential for enterprises like Twitter.

After eight months of organizing, and seeing many steps along the way where we might fail, our group had prepared for wherever we might focus next. And so, we published ideas to win over shareholders that we could also play forward to converting the next online platform.

With shareholders in mind, we wrote an FAQ to respond to skepticism. “You might be wondering,” it began, “1. Can’t users buy Twitter stock already? We mean ‘buy’ as in, buy-out or acquisition. But, we’re proposing a step before that – to explore models through which it could sell to its users and other stakeholders, with broad-based ownership and accountability.” And in the spirit of cooperation, we posted four scenarios Twitter could study: a full buy-out that creates a user’s trust, a partial buy-out that puts users on the board, a news consortium, or even a crypto-token issuance moving Twitter’s value onto the blockchain.

We also explained why cooperative models promise to increase Twitter’s value in general. First, user commitment that stems from real co-ownership can be far more powerful than any “sense of ownership” an investor-owned company can offer. Owners are more likely to be frequent users and to care about the service. Companies owned by workers tend to be more productive than their competitors. Second, when a company’s users are also its owners, information sharing can happen more freely; users feel more trust in sharing information about themselves, and the company can be more transparent in what it shares with its users. And third, a more diverse set of stakeholders with more varied incentive structures can result in greater resilience for cooperative businesses.

If Twitter and the Internet have one dark side, it’s the den of trolls. These are users who feed on stirring up controversy, often targeted hate speech and abuse against, for example, #BlackLivesMatter. But here, too, cooperative organizing holds out hope of a more inclusive economy. In April, we hosted another webinar to keep momentum, this time with three governance experts. New solutions to prevent trolling emerged, including improved accountability through electing users to the board, and sortition, a process of selecting a representative set of stakeholders to weigh in on decisions. We also have faith that people would steward the platform if they became invested as user-owners.

user commitment that stems from real co-ownership can be far more powerful than any “sense of ownership” an investor-owned company can offer

Support for #BuyTwitter finally came in from the cooperative movement. 50 leading organizations, from the National Cooperative Business Association, to credit unions and law firms, signed a letter to Twitter shareholders supporting our proposal and offering expert advice. Ed Mayo from Coops U.K, along with Catherine Howarth from U.K.-based investor advocacy nonprofit ShareAction, coordinated a nationwide poll that found some 2 million individuals would buy a share of cooperative Twitter.

In the final weeks before the general meeting, we mobilized all of our strategic capacity. We relayed emails from well-known activists and sent a flurry of tweets at Twitter co-founder Ev Williams, who owned 6% of the company himself. We needed 50%+1 for our proposal to pass. We were hoping for at least 3%, since that would make us eligible to resubmit a stronger proposal next year. Yet amid all of the buzz in press and publicity, our ability to gauge which way the vote might go was limited to a few dozen tweets from Twitter shareholders.

At the meeting, Jim and I found seats among a few dozen other shareholders. We listened to Jack Dorsey’s remarks about Twitter as a new utility. After reviewing three resolutions for three board seat elections, Jim spoke on behalf of our proposal to study democratic ownership. In 20 years of this work, he said, he’s never seen such enthusiasm. He mentioned one supporter even tweeted a YouTube video of him singing and playing, “Buy Twitter, or Bye Bye Twitter.”

Twitter’s general counsel read the results. Our proposal “did not pass.” The meeting closed, Jack thanked everyone again for investing in Twitter, and people made their way out.

Jim and I stood up to go, and Sean Edgett, Twitter’s Vice President of investor relations, came over. “You got 4 percent,” he said. I burst out, “Wow- we did it!” Sean kept an even smile. Jack came over to join us, and the four of us talked briefly about the vast opportunity for Twitter to learn from the cooperative movement.

Before we left Twitter headquarters, Jim and I tweeted the good news.

According to Twitter’s SEC proxy filing, our proposal received around 36 million shares in favor, about 4.9% of all shares. With well over the 3% minimum to resubmit, we can – and very likely will – come back next year with a better proposal to democratize Twitter.

Twitter’s opposition statement to our proposal said it couldn’t be done. The truth is, even some of our strongest allies suggested it was too complex and we should give up hope. But other shareholders and even a venture capitalist saw promise in a cooperative conversion.

Shortly after the meeting, I received an email from a stock market analyst who supported exploring cooperative ownership. “This study could be a game changer,” he wrote. “You have legitimacy now from the shareholder vote. That carries weight. Leverage it to the fullest.”

To grow the cooperative movement, we can convert even the most dominant enterprises and utilities. It took several decades to transform the Associated Press, but time moves much faster for Internet startups and bad news. And by going up against one of the largest companies in Silicon Valley and a major player in world news, we made the case for user-ownership, advanced the idea of cooperative platforms, and created strategic capacity to go further.

In the renewed fight for #NetNeutrality, it’s easy to see how broad-based ownership and accountability of digital platforms also requires ownership of Internet data and service, too. Comcast, for instance, is running misinformation ads on Twitter, but 100% of the responses call them out for lying. Our #BuyTwitter organizing group will continue putting pressure on Twitter to study cooperative alternatives, through direct conversations with employees and if necessary, another proposal. You can get involved in that effort and the fight for a cooperative Internet by following @BuyThisPlatform, adding your name at BuyTwitter.org, or joining the discussion in the #BuyTwitter Loomio group.

What does it mean to take ownership of our economy and make it more inclusive? Exploring that question must involve people outside of the cooperative movement. We have to throw our weight behind efforts like #BuyTwitter, investing in cooperative organizing. We can write more op-ed pieces to provoke attention, engage in social media to shift the conversation, and circulate petitions and start online groups to connect with allies.

#BuyTwitter showed what it looks like for the cooperative movement to change from a niche within the economy to a new norm for economic inclusivity. Venture capitalist Albert Wenger supported our shareholder resolution specifically because it was a new model for tech enterprises. Yet, cooperatives have been a key source of innovation and benefit for centuries. The food co-op wave in the ‘70s brought organic food into the mainstream. The credit union sector helped pioneer direct deposit.

Silicon Valley takes credit for discovering and serving these and other unmet consumer needs. Yet, their corporate governance allows founders to retain absolute control through multi-class shares, which give them controlling voting rights. Jim calls this a “democratic-free zone.”

Instead of being a source of models and product ideas, we can organize the cooperative movement to play a leading role in connecting users and workers, amplifying their voice in improving Twitter. Together, we can make a more inclusive economy for all, by democratizing the digital platforms we all depend on, starting with our primary news utility. ↑↑