I read John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me for the first time in October when Wings Press sent me a review copy in preparation for GEO’s celebration of the book’s 50th anniversary.

Though I knew of the book, and, I’m sure, had heard discussions about it in the past, I never felt compelled to read it. As I suspect was the case with many blacks, I probably thought I knew all about what he had to say, and anyway, what could a white man tell me about being black?

Notwithstanding, I was often stunned while reading the book. I found the incidents that Griffin described as plain shocking. For many days after, too, I was disturbed by what I had read. I had never heard of some of the things that Griffin points out, such as white bus drivers holding black people hostage on buses when they wanted to get off to go to the restroom, or refusing to let them off at their stops. I never realized the extent that black people were still – in 1960 -- at the mercy of any “psychopathic” white they were unfortunate to be near. After all, chattel slavery was “over.” However, a large part of the issue of my own ignorance of the severity of what blacks experienced 95 years after slavery allegedly ended is that the racial terrorism against African people was more open and vicious in the “deep South,” which in many ways excluded South Florida where I grew up. At any rate, somehow I missed understanding what the day-to-day existence of black life in the 1950s and early 1960s was like in those southern states of Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama and Louisiana.

After reading Griffin’s simple but powerful narrative, I began to look at this society today in an entirely different light. White people have come a long way, but where, pray tell, did that rabid racism go? I don't visit the deep South much, but my brief visits support the theory that the “hate stare” that Griffin felt from whites and described has now transformed into the eyes-averted “I don’t see (acknowledge) you” look. But in many places, including notoriously racist states, white people are more "civilized" and businesses-minded and many seem to genuinely treat people of color like human beings. [1] But we know (at least black people know) that racial hatred is just under the surface: we get reminded often with outbursts ever so often with the violent incidents such as the murder of James Byrd[2]; it manifests in the continued rancor over the election and presidency of Obama, probably in the murder of Troy Davis, and the many public exposures over the years of some government or corporate official’s racist remarks or actions.

That there has been substantial progress in human rights for African people there’s little doubt. But when one looks at progress through the lens of power and self-determination, there is much doubt about advancement. But progress, too, has a personal component. Just as Griffin was moved to take a personal stand, I believe we all must. Where do things stand now as far as dealing with racism and internalized oppression, the shadow side of America’s purported democracy? The greatest tribute to Black Like Me would be to take the work to eradicate racial and class oppression a higher level. Where would that start? With us -- those with the consciousness or curiosity or the caring to read these articles. Our personal consciousness and convictions can lead us to work with others of like minds to create organizations and institutions to make a difference. In this way, our individual acts can affect great change.It is heartening to have groups like Everyday Democracy, based in East Hartford, CT, which has been working since 1992 with A Guide For Public Dialogue and Problem Solving to tackle racism in communities.

Black and white women who have genuine love and appreciation for each other pause to pose for a photo during the Eastern Conference for Workplace Democracy in Baltimore in July. Shown are Cheryl Robin, LPC and Erin Rice co-op advocate and teacher from Baton Rouge, La.; co-op researcher Jessica Gordon Nembhard, worker-owner at Lagniappe Lifestyle Services in New Orleans Swameca Seals, Paula Spero, empowerment counselor from Baltimore, and blog author Ajowa Nzinga Ifateyo.

The worker cooperative movement – mainly the Eastern Conference for Workplace Democracy and the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives -- for many years also has been leading the country in dealing with inclusion in ensuring representation on boards from marginalized communities, and having workshops to deal with the issues. Some worker cooperatives like Rainbow Grocery even have anti-oppression committees in their workplaces. The U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperative formed an Inclusion Circle in 2007 to ensure that the membership was educated on the issue of inclusion as well as organizing work activities to make sure the cooperative organizing was available to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina’s devastation. Things have fallen off now, for a number of reasons, including an attempt to get people to look within for racism in their own “personal” beliefs and actions, but I’m hopeful that the work will continue.

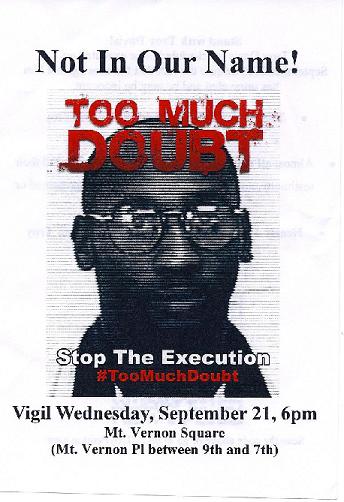

And more recently, I was impressed by the broad base of the movement to try to stop the unjust execution of Troy Davis. I loved the “Not In My Name” posters as it seemed to me that white people were more awake to how historically state execution has been misused and used in an historically white supremacist tool.

As a rule, young whites seem to be much more progressive on the race question. The young folks in the North American Students of Cooperation, also known as NASCO personify this. NASCO does anti-oppression training on its boards and its student cooperatives all around the country. The organization is leading the anti-oppression work in the country. At least a couple of NASCO folks have formed Anti Oppression Resource Training Alliance, or AORTA, to actively work on these issues in the larger community.

But while these great things are happening I bet that most black people can tell a story about wonderful people, or liberals or “progressive” whites who would invariably say or do something so terribly racist even though they professed to believe in “inclusion,” “equality” “worker power,” or “black political power.” This is because we haven’t acknowledged the powerful brainwashing that takes place in America, as well as the structural and institutional nature of colonial oppression. No one really escapes indoctrination of internalized superiority/inferiority. Racism is as American as apple pie. It's built in. It's the water that the fish swims in, and so there's blindness to it. By everyone. A conscious effort is needed by us as individuals to recognize it, deal with it, to learn about culture different from our own and to expand our perceptions.

In Black Like Me, Griffin wrote about his discussions with whites who sincerely professed to want to end discrimination, yet were hampered by their own “unconscious racism.” After reading Griffin’s words expressing his own unconscious racism and pointing out many examples of it operating in whites, I couldn’t help but wonder where might the world – white people’s consciousness in particular -- be if Griffin’s teachings on this subject were heeded, taught and expounded upon.

Even today, many whites --especially liberal or progressive whites-- do not get this, do not understanding that they have been brainwashed with white supremacist ideas and images -- through schools, churches, the media, parents, our so-called leaders, any and everywhere. We all get mind-controlled. That’s why their racism bursts out of their mouths before they know it. The same happens with black people except for us it is usually some self-hating, anti-black remark.

Reading Black Like Me also made me think back at the black people who I know who are modern day versions of the rabidly self-hating black Christophe on the bus ride to New Orleans, who berated the other blacks as ignorant, while thinking of himself as special, more like the white man. There are so many modern version of this one by blacks who had some aspect of self-hatred like not wanting to identify as black, or not wanting to be like “those other” black folks, or “poor,” or “uneducated blacks. For blacks, self hatred is sewn into the very fabric of American life. And oh how far black people could have come if we could have truly understood some the ways internalized racism had its genesis, and being conscious of where their thoughts originated. I mean we know it – intellectually – but even reading Griffin’s descriptions somehow brought these experiences into a whole new light. (I am not suggesting that it was the recent terror and brutalization that caused self-hatred, but hundreds of years worth that started with slavery and got passed down through generations. Most conscious[3] blacks “know” that the brutal treatment from slavery still today is largely responsible for debilitating internalized oppression that makes it difficult for blacks to organize in our own interests.)

So what to do? Where to start, or restart?

I believe nothing we will do will be truly successful in the end without starting with examining ourselves and rooting out racist indoctrination. Everyone must meet your shadow racist. Examine those thoughts that we have and feel guilty about. (Guilt is an excuse to do nothing. Turn guilt into action.) How much “real”[4] black history do you know? (Ever hear of the existence of "Black Wall Street," the burning of whites of the town called "Rosewood," or the African presence in North America written in the book They Came Before Columbus for starters? Better yet, talk to your parents and grandparents and other elders in your community.) This is an "oldie," but still a "goodie": For whites, how many black people do you really personally know who are different from you and you regularly share conversation with? For blacks, how many white people do you really know, talk to or interact with (hint: you don’t have to put all your “trust” in whites)?

I think a great start is for everybody to read Griffin’s works. Whites would do well also to check out Tim Wise’s White Like Me: Reflections on Race from a Privileged Son. For blacks, Dr. Joy Angela DeGruy‘s book and study guide on Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing. Others before her have done great work such as Na’im Akbar’s Breaking the Chains of Psychological Slavery. Everyone should read Rudy Aunk’s Doublespeak In Black and White: America Needs a New Idea: The World’s First Cultural Poisoning Self Test. Bi-racial folk, and immigrants and other people of color should read both, especially those who “identify” as white.

Self examine. Learn. Discuss (with self or others). Know yourself. Visualize a different kind of society than the one we currently live in. Really examine the idea of “The Other.” What would the world be like if there was no "other"? Then act out of our own sense of love and justice. Do the one thing that you think can make a difference in the world.

That’s what John Howard Griffin did. And he changed the world.

[1] Certainly a part of this is “big city” aversion with most people black or white. But I feel something else is going on that is part of that “Invisible People” thing.

[2] James Byrd was dragged behind a truck and killed in 1998 by three white men in Jasper, Tx. Click here for more information.

[3] Black people who are “awake” to the oppressive conditions under which African people dwell in the world; we usually define ourselves as “African,” recognize that we are colonized, are proud of our history and culture, and we are usually most distinguished by natural hair (though this would be refuted by blacks who wear their hair straight), and/or African-styled clothing, colors and accessories and who understand that black history began in Africa as a free people, not in America as slaves. We have not bought into the American Dream lie.

[4] History written from the perspective of black folks, not that which serves as an ideological underpinning to white supremacy, or there is some semblance of fairness or objectivity.

Add new comment