Coming Alive In Dangerous Times (1961-1983): Chapter 4

[Editor's note: this is the fifth installment of GEO founding-member Len Krimerman's new memoir. You can read the preface and introduction here, and the first three chapters here, here, and here.]

If you’ve made it this far – Congratulations! However, as I warned earlier, that journey was to be a prelude to your own coming alive memoir. In this chapter, my role shifts to that of a “peer mentor” offering suggestions and encouragement. But how exactly and most usefully to do this – especially since my own experience writing memoirs, coming alive ones or otherwise – is so limited?

If you’ve made it this far – Congratulations! However, as I warned earlier, that journey was to be a prelude to your own coming alive memoir. In this chapter, my role shifts to that of a “peer mentor” offering suggestions and encouragement. But how exactly and most usefully to do this – especially since my own experience writing memoirs, coming alive ones or otherwise – is so limited?

It took a while and several faulty starts, but after a long walk on a mild November day, it struck me that I needed to somehow take more of a back seat, and enable your questions to set the direction for this chapter. So this will be a learner-centered chapter – as far as possible, since right now I’m still the one writing it.

Below in Bold Italics, you’ll find eight questions that I imagine may have already occurred to many of you. To these I’ll respond by drawing on my own experience, and that of my wise hour exchange editors, in writing this memoir. Usually, I will engage an imagined reader in dialogue; in one case, where we discuss getting past writer’s block, I’ll appeal to some helpful reflections from some much more experienced writing mentors.

Obviously, this might land us in a dilemma, as the questions I will pose may entirely miss the mark, rather than being ones you might naturally raise. But we need to start somewhere, and at the end of this chapter I’ll suggest a way out of this dilemma, a way for your actual, not just imagined, concerns to take a much more central place.

Here’s the first of the “your” questions:

1. Why should we think that our own lives are really worth writing a memoir about?

LEN: Most probably, we all experience this kind of self-doubt, though not everyone admits it. And I’ve certainly had my share.

But there’s a prior question you may want to consider: “What do we see as the value, or worth, of a coming alive memoir?” Or, better perhaps, “For whose benefit is such a memoir written?”

Here’s how one of my editors responded to this question:

….My answer to what discourages people from writing memoirs specifically is the tussle between ego and heart. It's a balancing act to believe our stories are of value... of service to others without the attachment of vanity in the telling. As a recovering Catholic, this was deeply embedded into my psyche. Why should YOU write a book? Why would anyone want to hear from YOU?....What makes YOU think your tales are "better" than anyone else's. Yada, yada, all that crap….

EVERYONE has great stories to tell. We hunger for connection and relationship. The root of that is storytelling. Babies say, "again" and reopen books. Kids want to hear how their parents fell in love. Adult children crave the answers to their ancestry, sometimes too late to ask their relatives. Stories around the fire are the oldest method of communicating and they are coming back, with an insistence. We want to reconnect; memoirs give us permission to do that.

The sum of the above is to make the point that it's not only ok to write our memoirs, we have a responsibility to do so.

In short: if your memoir does its job – enabling your coming aliveness and gratifying your hunger for human connection – would it then be worth writing, even if other people’s memoirs might be more fascinating or heroic?

Imagined Reader (IR): Yes, it would seem so.

LEN: You don’t sound all that convinced. So here are a couple of thoughts to ponder. The first comes from an interview of novelist Wally Lamb; it’s his response to the question, “What is the most valuable advice you received as a young writer?”

“When I was an MFA student at Vermont College for the Fine Arts, my teacher, Gladys Swan, told me I should never write for a preconceived audience. Rather, I should write for myself and have the faith that the audience that was meant to find my story would find it.” ~Wally Lamb

In a very similar vein, our coming alive guide, Howard Thurman, once wrote:

“There are two questions that we have to ask ourselves. The 1st is " Where am I going?" and the 2nd is "Who will go with me?" If you ever get these questions in the wrong order, you are in trouble.”

What I think he means here is that we must first find and listen to our own genuine voices, and then decide who to share our life journeys with. A coming alive memoir is a way to do this: it gives primary importance to Thurman’s first question. And this enables us to produce something of real worth for ourselves, regardless of how it may be judged or evaluated by others, or how it compares with what others may have written.

2. What got you going on your own memoir?

2. What got you going on your own memoir?

LEN: My answer here needs to start at the very beginning of the memoir process, and actually just before it. At the outset, before any actual writing, there were two things I knew would be essential – much more than helpful – for me. The first was a safe, sanctuary-like space, one that would protect me against distractions and interferences of all sorts: e.g., other obligations, neighbors, family members, repair people, phone calls, texts, loud traffic nearby, etc. You can find this sort of supportive writing environment in many different locations: at home, in a library, a good friend’s available study, or on a remote mountain trail or ocean beach. Often, within my safe spaces, I felt allowed to write as if nothing mattered more than bringing the memoir to life. And this certainly helped to get me going.

IR: But how do you keep your “safe space” quiet, and protected from interference?

LEN: It’s not always easy, especially if you are living with others, or have no real control over a room in a public library. That’s why I sought out a number of separate spaces: a fairly solitary basement room at home, an under-utilized library in my small town, a friend’s office he hardly ever used, and, occasionally, a very quiet, welcoming, and inexpensive writers retreat in western Massachusetts called Wellspring House.

IR: And the second essential condition?

LEN: Along with a safe refuge, I also needed to set a reliably regular schedule of “protected times”: writing sessions that would be planned in advance for designated days and hours. (Much like establishing a regime for physical exercise, yoga, or meditative stress reduction.)

My own plan (not always adhered to) has been to write for several hours three or four times a week, giving myself generously-sized breaks, e.g., enough time for a unhurried two mile walk.

IR: That’s seems like a lot more discretionary time than most people can count on. Right now, for example, I’m limited to at best a single day, for a few hours, once every other week. Would this be enough time to write a coming alive memoir?

LEN: Intriguingly, many famous writers often complained of having too little writing time; Kafka, Tillie Olsen, and Dickens among them. It would be great to know how they overcame that obstacle.

However, there’s much we can learn from some less-than-famous memoir writers, who also had their struggles with “too little time to write”. On this, you may want to check out these web sites: The Momior Project – that’s the correct spelling; and this forum thread on Circle of Moms.

But even a few hours twice a month can yield good results, if you can keep that pace going. What helped me is an approach we could call “taking small steps” or “Slow Writing” (similar to “Slow Food” or “Slow Money”, etc.). Writing my memoir, taken as an entire book, can seem overwhelming. But selecting a single period to write about or recalling several stories of my coming alive doesn’t have that crippling effect. Try to imagine your memoir as a venerable but welcoming mountain that you are not planning to climb all at once, but a little at a time over many weeks (or months, or longer).

In this same slow vein, it may help to give each writing session its own specific intention: e.g., “today I will be recalling stories from my military service”, or “from my adolescence”. Once that intentionally narrow focus is fixed, stay with it. You can put any other memories or thoughts that emerge during your session aside, or onto a notepad, to be considered later.

In my own case, it took around ninety-five writing sessions over eight months before a decent first draft emerged; each session usually produced, or revised, about three or four pages. Given your much heavier time constraints, your memoir might take two years, or even more. (Or less, if you are a faster writer than I am.) In the beginning, you might find this slow pace disconcerting; I certainly did at first. But gradually I found a kind of relaxed pleasure in it and the often surprising details and connections it allowed me to recognize. Gypsy Rose Lee, the actress and burlesque queen, had it right: “Anything worth doing well is worth doing slowly.”

3. Is there a best way to tell my stories; and which stories should I include?

I’m not at all sure there is any one best way. One thing I learned from several of my editors was to include personal stories. They strongly suggested that rather than just describing external events or situations, I needed to let readers know how I and others around me had been affected or changed, and what feelings were provoked or awakened in us. For example, when the state troopers pulled us over in Mississippi, what emotions did this trigger, and how did we feel when we recognized the troopers’ benign intentions?

Additionally, what I found useful is to write those stories – initially – as if I were telling them to a close friend or family member. This enabled me to get something of my own down on paper, even though I knew it was imperfect at best. (It’s often easier to rewrite or revise, than it is to start from scratch.) At this early point, I banished the critic within, who would have demanded lots of detailed self-editing and reformulation. Instead, I tried to write truthfully, clearly and concretely, and from the heart.

Eventually, you may want to share those stories with others who are good listeners, who can raise questions that awaken or sharpen your own creative voice, and who support the kind of coming alive memoir you have chosen to write. But this takes us to your next question.

4. Would you recommend working with another person as a mentor?

LEN: That would largely depend on how comfortable you feel working with that other person, and with their style of mentoring. Some questions it might help to ask yourself include: Do I trust her with my personal memories and reflections? Is she supportive as well as candid? Does she listen well and ask me questions frequently, favoring these over direct instruction? And does she recognize what’s uniquely involved in a coming alive memoir?

It may sound clichéd, but my own memoir would most probably have never gotten beyond my own mind and onto paper without a great deal of assistance from a host of peer-to-peer mentors. Not only did they make me feel far from alone, but they continually spotted gaps or murky passages I had missed, raised questions I needed to address, and much more.

It may sound clichéd, but my own memoir would most probably have never gotten beyond my own mind and onto paper without a great deal of assistance from a host of peer-to-peer mentors. Not only did they make me feel far from alone, but they continually spotted gaps or murky passages I had missed, raised questions I needed to address, and much more.

IR: But I don’t really know anyone I’d consider asking to be a writing mentor. How can I find someone to take on that task?

LEN: You might want to try something similar to what I mentioned in the Introduction: put out a call, in your own community or a group you belong to, for mentoring assistance. I was able to attract over thirty readers in this way, through my local time bank here in eastern Connecticut, which is connected with over 400(!) similar labor exchanges throughout the country. Many of these very helpful readers had considerable past experience in proof-reading, editing, and providing constructive feedback to authors. And those with less experience lent both their enthusiasm and fresh perspectives to the comments I received. Most of my peer mentors were virtual partners, which worked for me, as so much of my other work is done online.

If there is no time bank in your community, you might be able to get your local library to help bring together a group of memoir writers, much as mine has put together groups of mystery story or historical novel readers.

Or you might want to help start a local time bank, an idea we’ll return to in the next chapter, as part of our focus on the “Memoirista Revolution”. If so, here again is the link you’ll need: http://www.hourworld.org/.

5. What if I encounter writer’s block, or some part of the memoir just won’t flow no matter how much it gets revised?

Good question. This quote might help a bit, just to see that blocked flows are far from uncommon:

“I get a fine warm feeling when I'm doing well, but that pleasure is pretty much negated by the pain of getting started each day. Let's face it, writing is hell.” William Styron (author of Sophie’s Choice, and lots more)

Even accomplished authors have their struggles. But they manage to push through. How do they do it? There are probably almost as many answers as there are writers, but here are some I’ve found helpful.

First of all, you may want to check your writing environment. Does it need amending? Maybe, at this particular point, you require an even safer refuge, or writing sessions of greater length?

I had to face these possibilities after several unsatisfying efforts to revise this very chapter. Somehow a graceful shift from recalling my stories to mining them for suggestions others would find useful for their own memoirs kept eluding me. After the third or fourth revision, I decided to seek a new and even more distraction-free venue, and postpone other work so that drafting this chapter would become my unrivaled priority.

Here’s another suggestion to help release your creativity, one often recommended by writing mentors: try writing non-stop for a short period without thinking or judging. A good statement of this exercise – a counterpoint to the William Styron quote – is provided by Wally Lamb, who has “facilitated writing workshops at a maximum-security prison for several years.”

Q: What is your method for overcoming writer’s block?

A: I complain on paper. Try this exercise: Grab two or three sheets of blank paper and a pen. (No computer.) Title the first page "What I Will Write About." Then, for ten minutes, write without stopping, even if you have to resort to whining about how hard writing is or why your stomach is gurgling. You don't have to come up with anything brilliant or profound. You just have to keep moving the pen across the page. Don't stop and think and then write. Think while your pen is in motion. At the end of ten minutes, read over what you've written and underline whatever seems most interesting to you. Chances are you'll have a lot of throw-away lines but what you've underlined just may lead you into your next writing project. Voila! Writer's block vanquished. (From an interview on Gotham Writer)

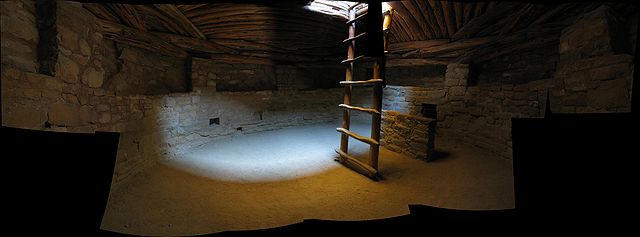

Another extremely useful tool is Wendy DeGroat’s Kiva Ladder for Creative Writing. Wendy is a poet, a librarian, and a writing mentor, and she has worked with people who, at first, often had trouble coming up with pages of writing.

Kiva Reconstruction. Photo by BenFrantzDale. CC BY SA 3.0

Here’s how her process works. There are four steps to the Ladder: Observe, Appreciate, Clarify, and Suggest; you’d be taking them in just that order. As Wendy puts it,

Imagine descending a kiva ladder as you discuss a creative work. Begin by observing what’s on the surface, then deepen the analysis gradually, each rung of the ladder moving you closer to the work’s core.

(Note: a “kiva”, in its original sense is a room, often underground and often of a sacred nature, where tribal ceremonies would take place. Such rooms were utilized by indigenous tribes in the American southwest.)

She continues, offering examples of each step:

What do observations sound like?

Resist adding judgments such as “I really liked that” or “that turned me off” to your observation. Notice, name, and summarize in a matter-of-fact manner.

• The poem is written in free verse and organized into four stanzas with six lines each. Images of light and brightness appear several times.

• In this story, two people argue about walking the dog, and while they’re arguing, the dog disappears.

• In the last paragraph, the point-of-view shifts from third-person to first-person. The first-person narrator sounds angry or bitter.

• Current action is written in present tense; flashbacks are written in past tense. In the escape scene, the sentences become much shorter.

• There are many long vowel sounds, mainly “o” sounds, in the description of the funeral. I also noticed four clichés.

What do appreciations sound like?

• The images of light and brightness created a joyous, almost reverent mood. I especially liked the vivid description of sunlight dappling the rocks.

• I could sense the speaker’s fear through vivid verbs like peered, crouched, and clutched.

• The short sentences in the escape scene heightened the suspense.

What do clarifications sound like?

• I’m confused about the age of the narrator. I thought he was a child, but his vocabulary sounded more like a teenager.

• Is the third paragraph part of the flashback?

• I got lost in that five-line sentence in the opening paragraph. I reread it, but I’m still not sure I understand it.

What do suggestions sound like?

• Consider leaving out the part about the parrot. It’s funny, but it distracts from the main point of your essay.

• Use more vivid verbs and sensory details to convey the anxiety and exhilaration the narrator felt as she climbed toward the diving platform.

• Try starting with the campfire scene; it would hook the reader right away. You can fill in the other details later.

• Loosen up the dialogue so it sounds more like a conversation.

Wendy’s Kiva Ladder process is typically used by two people – a writer and a writing mentor or facilitator. But you can play both roles. Review the recalcitrant piece of writing you are working with as if you were your own external mentor: start with a straight-forward observation of what you see on paper; next select – underline – passages you appreciate and want to preserve; then focus on clarifying places that seem to you fuzzy or otherwise obscure, awkward or out-of-place; and, as a final step, offer yourself suggestions that address what’s missing or needs to be altered.

Of course, you can also ask that friend who listened to you earlier – or anyone else – to act as an observant, appreciative, and constructive mentor.

6. All of this is well and good for people who communicate primarily by the written word, but does it really work for those who do not, and prefer to speak or sing or dance their stories, or to rely on visual images?

As we saw in the Introduction, memoirs need not be written exercises, and can be expressed in many other ways. This memoir of mine is offered here in written form, but I have often presented it, or some of its parts, much more directly, as one speaker to others, without notes, a written script, or a power point presentation, etc. (Some day, I’d like to try giving it a non-verbal form.) Throughout the earlier chapters, we have understood memoirs not as exclusively filled with words, but much more broadly.

Given this, all of your questions and my responses in this chapter should be re-construed to avoid any apparent bias or preferential treatment in favor of wordsmiths. For example, our first question would be understood as: “Why should we think that our own lives are really worthy of a memoir – however created, whether written, sung, told, danced, or visualized?”

Still, a sticky problem remains: can these divergent forms of memoir appreciate and support each other? Arising from such very different places, can we expect that they will be able, or even want to, collaborate? We’ll return to this question in the following chapter, where we consider the goals and prospects of a Memoirista Revolution.

7. You’ve frequently emphasized that coming alive memoirs are really different than other memoirs. Could you go over the contrasts again?

Sure. As we’ve seen, coming alive memoirs:

• focus on enabling us to become more inner–directed; they are not written to captivate, impress, or otherwise appeal to others (though they may, and often do, have these effects);

• utilize peer-to-peer mentors more than professional writing coaches;

• draw upon editors who receive time credits or labor hours rather than dollar fees;

• are typically made available on an “open source” or “pay it forward” basis, rather than being sold through commercial outlets. For example, as mentioned in the Introduction, you can now read mine for free on the GEO web site. All GEO asks is that you offer me constructive feedback or create your own coming alive memoir, for which you also can get help with from other peer mentors on the same basis;

• are not intended to be finished, or to reach a pre-designed final stage. On the contrary, they remain incomplete and open to critiques, amendments, new perspectives. (Recall here, from the Introduction, Dewey’s notion of “democracy” as always needing to be reborn.)

• are understood broadly, as diverse forms of communication, rather than being solely composed of the written word.

• believing that we all have great stories to tell, they open opportunities to join a “Memoirista Revolution”, where the “lion’s stories” – those so often ignored or silenced – are told, shared, and appreciated within a culture of mutual aid: “Each One Tells Their Own Story and Helps Others Tell Theirs.” (More on this in the next chapter.)

8. What about your promise to go beyond these imagined questions, and to give our actual concerns and questions a more prominent place?

Just send them all to me at lensmemoir@geo.coop. I will email back responses, which I hope will provoke further dialogue between us. My plan is sift through these dialogues, and draw out your real questions to augment those imagined in this chapter. There’s no strict deadline, as my memoir will remain open as long as there’s interest in refining or expanding it. All of whatever you send, of course, will remain anonymous, unless you explicitly grant me permission to use your name.

Go to the GEO front page

Citations

Len Krimerman (2015). Your Turn Now: Coming Alive In Dangerous Times (1961-1983): Chapter 4. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/story/your-turn-now

Add new comment