The Power of Collaboration

Many people, including those in the labor and worker co-op movements, think that unions and co-ops are singularly mismatched. Logic has it that worker co-ops don’t need to be unionized since workers own and manage their businesses, and that workers in labor unions just naturally aren’t entrepreneurial but rather are used to resisting “the boss.” In addition, people may be familiar with large agricultural co-ops in the Midwest that fight with unionized workers, or with food co-ops that resist worker unionization.

What many people – even people in the broad co-op movement – don’t realize is that there are basically three types of co-ops: producer (like big ag co-ops), consumer (like food co-ops), and worker. In the first two types of co-ops, workers are not empowered with ownership and management control. Only in worker co-ops are workers in full authority. (Caveat: there are some producer and consumer co-ops in which workers are unionized, as well as “hybrid” co-ops in which workers are integrated into ownership and management along with consumers and producers.)

Many people are also unaware that the labor movement has a long and committed history of involvement in co-op development. Excellent treatments of this history may be found in The Practical Utopians: American Workers and the Cooperative Movement in the Gilded Age by Steve Leiken (2005), in which the author discusses the rich labor co-op movement in the US in the quarter century after the Civil War when “virtually every important American labor reform organization advocated cooperation over competitive capitalism, and several thousand cooperatives opened for business.” Another book that discusses labor’s involvement with co-op development is For All the People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America by John Curl (2009), which includes tales from the Knights of Labor and International Workers of the World.

Why Mutual Involvement?

There are a number of reasons why unions are interested in worker co-ops. 1) Unionized worker cooperators add to labor union membership, albeit on a small scale when compared with large corporations. 2) Union members involved in worker co-ops enjoy enduring empowerment that involves both ownership and control of management, aspects of worker control that labor sacrificed to great detriment after World War II (see Charles Post, Jacobin, June 6, 2015).

3) Businesses incorporated as worker co-ops are less susceptible to attack and decimation from capital, a scenario all too common as corporations abandon unionized areas of the country.

4) Worker co-ops help to build member and community wealth in the form of enterprise ownership. 5) Worker co-ops allow the labor force to respond to economic downturns with more flexibility than traditional businesses. If workload drops off or money is scarce, worker owners can agree to decrease everyone’s workload rather than laying people off, as unionized workers are forced to accept when they don’t want to give up hard-won pay. 6) Worker co-ops and the alternative economy movements in which they function can inform democratic practices in labor unions.

7) Building worker co-ops involves labor in constructive vs resistance work, enhancing worker and staff morale despite the fact that entrepreneurial work is as difficult, demanding, and rife with obstacles as traditional labor organizing.

There are also a number of reasons why worker co-ops are interested in labor unions.

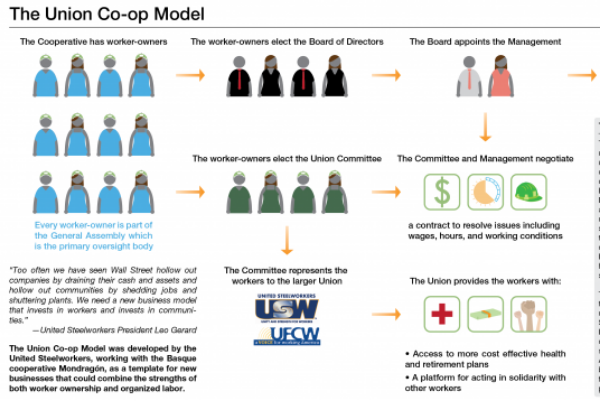

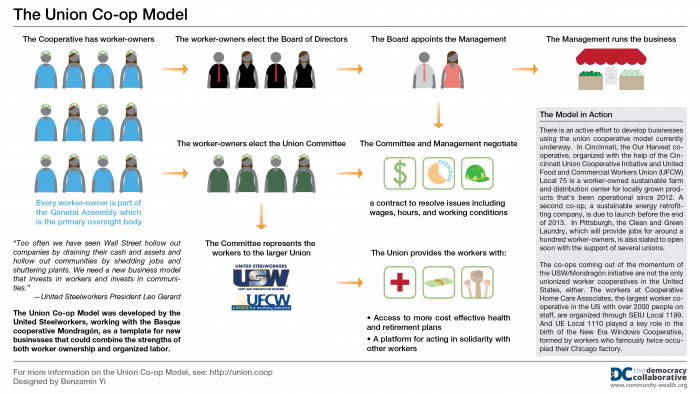

1) Affiliation with a labor union and the labor movement in general gives worker cooperators access to broad and deep anti-capitalist economic analysis. 2) Affiliation with a labor union offers worker co-ops the opportunity for action in solidarity on workers rights and opportunities in the community and broader economic arena. 3) Affiliation with a labor union can facilitate worker co-op access to pension and health care benefits. 4) Affiliation with a labor union provides worker co-ops access to organizing expertise and capital for co-op initiation. 5) Affiliation with a labor union provides worker co-ops access to model collective bargaining agreements, operating procedures and rules, and model grievance procedures. Such well-developed practices and procedures can contribute greatly to the smooth running of new worker co-op businesses, which often find themselves “reinventing the wheel” as operations commence and pick up speed.

Model Strategies for Mutual Involvement

Several models for labor / worker co-op collaboration are emerging as union co-op work gathers attention and commitment around the country.

The first and perhaps most efficacious model is the Multi-Union Incubator Model. In this model local, regional, and even national labor unions interested in forming worker co-ops come together to create an incorporated group, typically a nonprofit, to facilitate research, feasibility studies, business plans, and fundraising for new co-op businesses. When possible, unions can also provide organizing staff. Incubator efforts frequently make reference to Mondragon in Spain, one of the largest, most successful, and most long-standing confederations of co-ops in the world, which have demonstrated remarkable resilience in the face of global capitalist crisis. Agencies within the Mondragon network provide training and funding for new and existing co-ops, support mechanisms in the US that are still in nascent formation and available only in limited quantity, and which union collaborations can provide.

The first and perhaps most efficacious model is the Multi-Union Incubator Model. In this model local, regional, and even national labor unions interested in forming worker co-ops come together to create an incorporated group, typically a nonprofit, to facilitate research, feasibility studies, business plans, and fundraising for new co-op businesses. When possible, unions can also provide organizing staff. Incubator efforts frequently make reference to Mondragon in Spain, one of the largest, most successful, and most long-standing confederations of co-ops in the world, which have demonstrated remarkable resilience in the face of global capitalist crisis. Agencies within the Mondragon network provide training and funding for new and existing co-ops, support mechanisms in the US that are still in nascent formation and available only in limited quantity, and which union collaborations can provide.

One of the most promising developments in the US based on the Multi-Union Incubator Model is the Cincinnati Union Co-op Initiative (CUCI) in Ohio. CUCI grew out of a year-long study group that formally organized after the United Steelworkers and Mondragon announced their historic paradigm-shifting agreement in 2009. CUCI incorporated as a nonprofit in late 2011. It involves multiple labor unions--United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), Asbestos Workers, United Steelworkers (USW), Ohio AFL-CIO, and the Building & Construction Trades, among others--along with an array of community nonprofits and developers to create good, unionized, worker-owned jobs. In the first year of operation, CUCI created jobs for ten worker-owner track employees, with two hundred such jobs projected over five years. Their claim of an extremely positive ratio of dollars spent to jobs created is enviable and worth researching.

On the national level, 1worker1vote (1:1), is an expanded example of the Multi-Union Incubator Model. 1:1 launched in late 2013, but was based on work that began in 2009 which included the USW / Mondragon agreement in 2009, the USW / Mondragon / Ohio Employee Ownership Center (OEOC) Union Co-op Model Template in early 2012, and the Mondragon / OEOC Memorandum of Understanding in late 2012. Current affiliates of 1:1 include a wide array of labor unions and labor organizations, nonprofit development corporations, funders, Institutions of higher education, and religious organizations. 1:1 is working in up to ten cities around the US to expand the union co-op model. In early 2013, 1:1 was instrumental in facilitating the New York City launch of Mondragon University’s online “Social Economy and Cooperative Enterprise” course.

A second approach to union co-op development is a Partnership Model. In this model, labor unions become involved in worker co-op formation as one of a number of parties with leadership coming from another source other than the unions themselves. As in the previous model, the group also typically contains technical assistance providers, community based organizations, worker nonprofits, etc. The group, often incorporated as a nonprofit development corporation, takes the lead on multiple worker co-op projects, with labor unions joining in on projects related to their sphere of expertise.

An example of this model is the Wellspring Co-op Corporation in Springfield, Massachusetts. Wellspring is a nonprofit, incubator-type organization that has labor representation built into its board of directors, but unions become involved in specific worker co-op projects based on the relevance to their missions. Hence, UFCW Local 1459 is involved in a Wellspring greenhouse project with the anticipation that workers will be organized by the union, and that the union will contribute organizing and operating expertise and possibly some funding.

A third approach to union co-op development is a Network Model in which labor unionists, worker cooperators, and development professionals come together on a regular basis to share information that helps each participant further his or her own local work building worker co-ops.

An example of this model is the UnionCo-ops Council of the US Federation of Worker Co-ops (UCC USFWC), which has been operating since late 2007. UCC USFWC meets monthly by conference call with people from more than twenty states and occasional Canadian provinces, thirteen labor unions and worker organizations, and multiple technical assistance and funding providers. The group discusses and offers advice on participants’ projects; organizes workshops at conferences around the country, continent, and world; and makes presentations on radio and TV shows.

In a fourth Activist Model of union co-op development, employees organized by a union in a traditional business work with their union and selected technical assistance providers to buy out the enterprise when they’ve run into overwhelming obstacles with owners and managers.

In a fourth Activist Model of union co-op development, employees organized by a union in a traditional business work with their union and selected technical assistance providers to buy out the enterprise when they’ve run into overwhelming obstacles with owners and managers.

One example of the Activist Model is Collective Copies in Amherst, Massachusetts. In 1983, workers at Gnomon Copies ran into trouble with their owners/managers. Workers, who were members of United Electrical (UE), went on strike and ended up buying out their business with the union’s help. The business became Collective Copies (CC), which has been a thriving copy and publishing shop ever since, with stores in two towns in western Massachusetts. CC is also an influential leader in the local, regional, and national worker co-op movement.

A second example of the Activist Model of union co-op development is New Era Windows Co-op in Chicago, Illinois. In 2008, Republic Windows and Doors, a manufacturing enterprise in which the workers were also members of UE, planned to close due to bankruptcy. When the owners of the factory threatened to close the operation, leaving workers without severance pay and benefits, workers conducted a successful occupation of the factory not once but twice. Such difficult circumstances would have defeated most people, but not the workers and their union. The factory opened in 2012 as New Era Windows Cooperative, and is fully functioning under worker ownership and control.

In addition to these four models of union / worker co-op development, you may be able to think of others, or you may think there is overlap among the models leading to condensation. These come to mind as I review the work with which I’m familiar.

Examples of Unionized Worker Co-op Enterprises

While the current period of labor involvement in worker co-ops is still young, a number of actual enterprises are functioning and thriving or in the planning stages, in addition to Collective Copies and New Era Windows Cooperative mentioned above.

In Cincinnati, Ohio, UFCW is involved in Our Harvest Co-op, a worker-owned farm and food hub that launched in mid-2012. UFWC is also involved in the planning and implementation of Apple Street Market, which will serve as a consumer and worker owned “hybrid” food co-op with branches in underserved Cincinnati neighborhoods.

Two other Cincinnati unions – IBEW and International Association of Heat and Frost Insulators and Allied Workers – are involved in Sustainergy, a worker-owned residential green energy business.

In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USW is involved in the worker-owned Clean ‘n’ Green Co-op Laundry, which launched mid-2013 following that union’s historic agreement with Mondragon. This project utilizes “anchor institutions” – large businesses such as hospitals and universities that are “place-based” and would find it difficult if not impossible to move location – as purchasers of goods and services provided by the co-ops, thus providing solvent, sizable clients.

Despite the beating that organized labor has taken...it plays a unique and crucial role in progressive politics and the economy.

In Springfield, Massachusetts, UFCW is involved in Wellspring Co-op Corporation’s greenhouses project, which will provide organic greens and herbs to local health care and higher education institutions, among others.

In Worcester, Massachusetts, WorX Printing Co-op, which launched in 2014, is organized by USW. WorX provides an alternative to sweatshop-made and -printed textile products. Like most if not all worker co-ops, WorX uses environmentally friendly products and processes, another positive aspect of worker co-ops.

In Denver, Colorado, Communication Workers of America (CWA) is a principal in worker-owned Union Taxi Co-op, which was formed in 2009 after much protesting and lobbying as well as formidable resistance from existing cab companies. Because the taxi business is regarded as a protected public service, the number of licenses a taxi business can grant to drivers is limited. As a result, Union Taxi Co-op has not been allowed to grow to accommodate the number of workers who are interested in becoming members. Since late September 2014, more than one thousand drivers have joined CWA to set up a second worker-owned company (Green Taxi), a co-op that will support Uber and other drivers in Denver’s tightly controlled taxi industry.

In Los Angeles, California, Pacific Electric Worker Owned is a worker co-op organized by IBEW members that launched in late 2013. It provides full service commercial and residential electrical work and solar installation.

The Big Picture

Despite the beating that organized labor has taken from the conservative and corporate sectors of the US since the 1970s, it plays a unique and crucial role in progressive politics and the economy. Few if any other movements are as widespread, solvent, well organized, and well connected as labor unions and their affiliates. In addition, their understanding of how work can and should be organized to be most productive and rewarding simply isn’t on the wave-length of most people and institutions, including some co-ops. The ground work that labor has done over centuries to understand and rationalize work processes can be a great boon to worker co-ops that can avoid reinventing the wheel regarding operations and work relationships.

Despite the contributions that organized labor can and does make, the sector has given up too much over time to corporations and conservatives. Worker control of management and ownership of profit has been ceded to capital and must be regained. Evidence is increasingly clear that uncontrolled capitalism is badly damaging the planet, causing wide disparities in wealth, and becoming decreasingly effective in job creation. Labor must think deeply about alternative economy strategies if it is to survive. Complicity with capital simply hasn’t been a fruitful strategy. A much better ally is the worker co-op sector.

Go to the Regional Cooperative/Solidarity Economy Networks theme page

Go to the GEO front page

Citations

Mary Hoyer (2015). Labor Unions and Worker Co-ops : The Power of Collaboration. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/story/labor-unions-and-worker-co-ops

Add new comment